Translating Rabindranath Tagore’s Song-Lyrics

In the song-lyric numbered 230 in Gitabitan, Rabindranath Tagore's comprehensive compilation of such verse, we find his delight at capturing the loveliness of the world outside his window in a song-lyric: "I've caught uncatchable loveliness in rhyme's binds—/The loveliness of a distant night-bird/Singing at a late hour of the night/ Wings crimsoned by ashoka flowers of a departed spring/And a heart filled with the fragrance of fallen flowers" (my translation).

Tagore's delight in his accomplishment is understandable. The Bengali song-lyric is utterly delightful in the way it melds its intricate, lovely tune with harmonious and effusive words and vibrant images expressing the rapture of a poet-composer who has captured "loveliness" otherwise "uncatchable" in verse. After all, blending a beautiful melody with lilting words, the rhythms of thought with the rhythms of feeling, and the auditory imagination with the visual one is no mean feat. Although it is much shorter and simpler, one could compare this song-lyric with the celebrated romantic and effusive outpourings inspired by birds we encounter in Shelley' s "Ode to a Skylark" and Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale." Of course, the English poems are much longer and more complex; but it is also the case that the nineteenth-century Romantic poets did not think of setting their odes to music and were content to capture the ineffable beauty of the singing bird in the world outside their windows entirely in stanzas structured harmoniously and lines only suggestively melodic.

Tagore then had reasons to be excited. We who have heard the song being sung perfectly by some well-known singer and have some dealings with such poetry tend to be stirred as well by a lyrical impulse that has found a perfect musical form. Some Bengalis, and even a few foreigners who have heard songs such as this one, have been inspired enough by them to even attempt translating them. Tagore himself, of course, had thought fit for at least a decade of his life to translate them into English, and his fame in the western world depends substantially on his own translations of the song-lyrics of Gitanjali: Song Offerings.

And yet Tagore himself soon felt that anyone setting out to translate song-lyrics is embarking on a doomed enterprise. Disillusioned by the increasingly lukewarm and at times even critical reception in the west of later translations of his poems and song-lyrics, he eventually decided to stop translating them, and was eventually content to let others render his song-lyrics into print in their language. Let me quote representative thoughts that he had about the subject from his Bengali essays in my own rough translations, and from his letters, as collected, and at times translated by Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson in their Selected Letters of Tagore (2005). In the essay "Sangeet O Bhab" or "Music and Thought," for example, he says unequivocally, "Song-lyrics can't be read, they are to be heard"; songs express feelings in a way prose cannot. In certain moods, for instance in this 18 February, 1926 letter to Arthur Geddes, who had devised "musical settings" for a few songs, he said unequivocally, "Do whatever you like with my songs, only do not ask me to do the impossible. To translate Bengali poems into English verse form reproducing the original rhythm so that the words may fit in with the tune would be foolish for me to attempt. All that I can do is to render them in simple prose, making it possible for a worthier person than myself to versify them."

Tagore insisted in his essays that in songs the words and the music could not be separated. He also indicated that at best his song-lyrics could be translated into prose that had a whiff of music in them. This is also implied by the Sinhalese-Tamil writer and thinker Ananda Coomoraswamy, at one time close to the poet and translator of Tagore's song-lyrics into English. Introducing his work in 1912, Coomoraswamy observed about his renderings: "The translations convey only a shadow of the original poetry; they give only the meaning, that in the songs themselves is inseparable from their music."

Why then bother with translating the "uncatchable loveliness" of the song-lyrics into other languages, if so much is lost? One answer is that Tagore knew that the songs were his "best work"; as he once said in a letter to Edward Thompson. "I often feel that, if all my poetry is forgotten, my songs will live with my countrymen, and have a permanent place"; he believed they would be his most important "legacy." Anyone wanting to perpetuate his contributions and honor his memory by preserving his work for posterity, internationally or nationally, therefore, can do no better than translate them as well as the best works in other genres, despite the intrinsic difficulties and ultimately impossible nature of the task.

There are other reasons why Tagore embarked on such a "perilous adventure" in trying to capture the "uncatchable loveliness" of his song-lyrics in his Gitanjali: Song Offerings. One is that they themselves aroused the poet to attempt the arduous task of translation. Convalescing in his rural estate in Sealdah, East Bengal, he apparently felt a sudden impulse to capture the verse he had written in recent years in a representative selection. As he wrote to his dear niece Indira Devi Chaudhuri, aroused by the summer breeze in Sealdah, he felt a stirring in him to capture its music through creative work that would not be demanding beyond a point. Instead of writing original work, "I took up the poems of [the Bengali] Gitanjali. It was just that I knew I had started a festival of poetic delight in my mind once before, fanned by the zephyr of emotions, and so now I felt an urge to rekindle it through the medium of a foreign language."

This magical quality of the Gitanjali: Song Offerings would similarly kindle the imagination of quite a few people of different mother tongues—some poets but some not—to translate the song-lyrics, whether they encountered them in the original, or in their English renderings by the poet. These men and women ventured into translating them and other song-lyrics from other collections, not daunted by the "uncatchable loveliness" of the compositions, and even if they felt works translated convey at the end only a trace of the original loveliness. The net result, nevertheless, seems satisfying. As Tagore himself said in another context in his Bengali essay, "Sangeeter Mukti" or "Freeing Music," it may be necessary "to liberate what is being walled in and free all confined forces of the world—whether in music, or literature, or thought, or the nation, or society" (my translation, 50). Moreover, and as Tagore had claimed in an exchange with Dilipkumar Roy, a Bengali musicologist and musician, "the essence of a song is universal, even if its dress is local and national" (77). Why should translators then not attempt translating his songs for the world at large even if their loveliness is uncatchable in the last analysis? He himself had led the way!

Indeed, on a few occasions, Tagore even acknowledged that translating song-lyrics was worth the effort, necessary and even inevitable. After listening to the singer Rattan Devi---the stage name of the singer Alice Ethel Richardson who would eventually marry Ananda Coomeraswamy and became Ratan Devi Coomeraswamy, and who had recorded Indian music and performed Indian songs in concerts in England and America— Tagore observed: "Sometimes the meaning of a poem is better understood in a translation, not necessarily because it is more beautiful than the original, but as in the new setting the poem has to undergo a trial; it shines more brilliantly if it comes out triumphant." In this particular context, he was, of course talking about the singer's stage rendering of a Hindustani song in a foreign setting, but could not his observation be extended to his own translations of the song-lyrics and even of others who had done so into diverse languages as well?

My Own Experience of Translating Tagore's Song-Lyrics

I have been translating Tagore's verse for over two decades now. The songs are always so melodic that I soon became fully aware of the enormity of the task I had undertaken and often felt myself floundering. Nevertheless, I managed to contribute many song translations to the "Song" section of The Essential Tagore, that I co-edited with Radha Chakravarty (2011). Moreover, whenever I would hear a song sung by a favorite singer, I would go to my copy of Gitabitan and end up translating it. Sometimes I would go back to a song and translate it again, forgetting that I had translated it years ago. There is something obsessive about my efforts, and I am sure that was also the case with other translators. Surely, they had felt like I did after a while that the task was an impossible one—the loveliness of the songs in performance had lured us all to strive and strain to capture the "uncatchable."

Towards the end of the second decade of this century, I decided I would translate all 103 song-lyrics of the English Gitanjali in the sequence that Tagore had worked out for them in his book; the manuscript has been accepted for publication by a leading Bangladeshi publisher and should come out by early next year. Also, I had around 300 song-lyrics from Gitabitan that I had completed by the end of the decade, despite discarding quite a few of my earlier efforts. I am now in the process of readying them all for a publisher.

I feel that more than any other genre in which Tagore wrote, the song-lyrics reflect the length and breadth of his interests. His lyrical side, devotional nature and mystical moments, moments of happiness and grief, patriotism, love of nature and of his fellow human beings, thoughts about life and death and the after-life, vison for the future of his people as well as ruminations on his own fate, eco-critical consciousness, and sensitivity to the seasons of Bengal and its flora and fauna all come out vibrantly as well as musically in his songs. His flair for writing dance dramas, musicals and lyrical plays, his ability to produce songs for ceremonial and other occasions all lead to the song-lyrics. But above all, they are so compelling! This is how I and other translators, and of course singers and directors have been attracted to the songs and felt driven to work with them or on them.

What I would like to do by way of an ending is to present for readers one of my translations for the Gitabitan collection that I am finalizing as the conclusion to this paper. I'll only preface it by saying that I tried to follow the versions in Gitabitan as closely as I have been able to in every respect, including the figure they make on the page:

Dhay Jeno Mor Shokol Bhalobasha #94/43

Let all the love in me flow towards you

O Lord, let all my love flow, flow only towards you

Let my most ardent, my fondest hopes

Reach your ears, and only your ears

Wherever my mind is, and always, let it respond to your call

Let all things hemming me snap

At your summons and only at your summons

Let the beggar's bowl I had filled abjectly empty completely

And all the chambers of my heart fill up instead

O Lord, with your gifts, with only your gifts!

O my dearest friend, my innermost one,

Let this day be one in which all things beautiful in my life

Sound as songs, composed in pleasing tunes

O Lord, as songs meant for you, for only you!

[This is a much shorter and considerably rewritten version of a Virtual Lecture delivered at Tagore Centre, UC Berkeley on October 13, 2020]

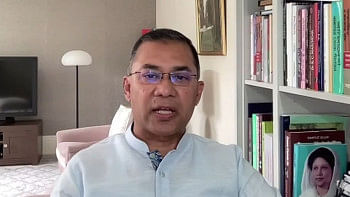

Fakrul Alam is UGC Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments