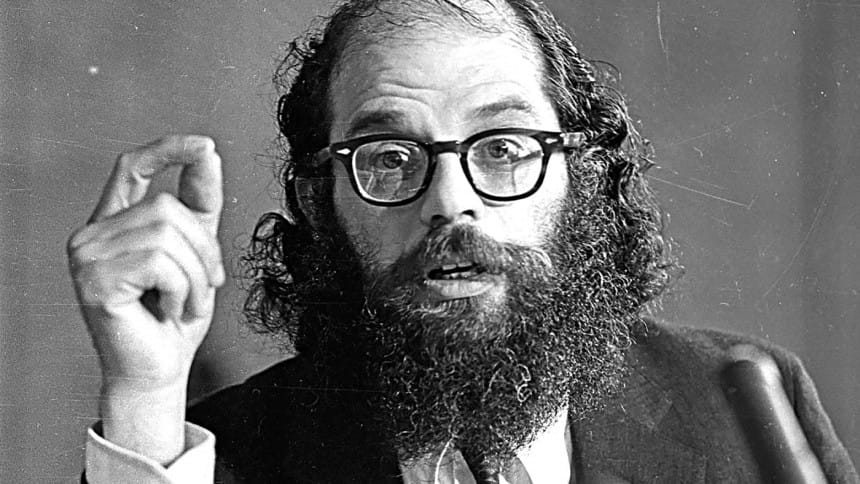

A Tribute to Allen Ginsberg on his 24th Death Anniversary

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, as much at home on the Kali Ghat as in Greenwich Village, is best remembered in Bangladesh on account of his poem, September on the Jessore Road. Year One.

I have a happier, earlier, memory of him standing outside his hotel in the Canadian city of Saint John on the day he was due to read to my students.

Saint John and other ports on the east-coast Maritime provinces had once been the gateway to Canada. Then ice-breakers opened up the Saint Lawrence River to year-round shipping. Saint John became a backwater.

We had asked Allen to come and read his poetic clarion call Howl as one way of putting the new, very small, branch of the provincial university, long denied to the city, on the map. We would bring the world into it again.

I have a photograph of Allen standing together with Chanchi Mehta, my old teacher, trouper and Indian playwright, local poet Alden Nowlan, and I. Allen is telling us that the previous night he had picked up the Gideon Bible by his bedside and re-read The Book of Ecclesiastes. "I have seen all the works that are done under the sun; and, behold, all is vanity and vexation of spirit." One long, bloody, bitter poem, was how Allen described it.

Alden Nowlan could have told him that, as an uneducated country boy who had been taken out of grade school to cut timber, he believed he had been sent by God to add books to that same Bible. Instead, he simply asked Allen if he'd like to compose a verse about the Loyalist Graveyard in which we were standing.

The hill-top centre-point of Saint John from which the rest of the city falls away is a graveyard. It is dedicated to those counter-revolutionaries who, preferring a mad king to a sane republic, fled north after their defeat in the American War of Independence.

A residual covering of snow packed into ice among the tombstones led Ginsberg to hazard what he thought might be a haiku (or what passes for haiku in a language with a wholly different orthography): "Many drunks have slipped on this snow and bloodied their heads on these stones."

Nowlan, himself struggling to be a poet, was covering Ginsberg's visit as a journalist for the local newspaper, The Telegraph-Journal. He had broken into journalism only because it was assumed he had finished high school. In fact, he had educated himself only by sneaking into a local library secretly and reading the biggest books he could find.

Arriving in Saint John, I inquired of Alden's whereabouts. As a student I had read and liked a slim volume of his poems about the rural poor. He is dying of cancer in hospital, they told me. When I went to see him, Alden had been advised that if he lived for two more days, he could expect to live for four, four more, eight and so on. Double or quits. Eighteen months later, here he was writing a full-page story on Ginsberg, using one of Allen's quips as a headline: LOVE IS A FOUR-LETTER WORD.

As a poet, Alden was not altogether happy with the fuss about Ginsberg's visit. His verse is flaccid, he objected, he's as sentimental as Longfellow. I reminded him I had repeatedly urged him to read his own poetry to our students. The trouble was, unschooled, he was shy of entering a university.

Alden did soon escape journalism to write poetry. A one-finger typist, he asked me, a two-finger typist, to type up his application for a Guggenheim grant. Three fingers must have been lucky: he got the grant. Among the many other poems he was to write was a very fine one about a journalist registering the death of Martin Luther King, "The Night Editor's Poem."

This poem catches perfectly the disjunct between the high-pressure professionalism required to set up a news story in print and the subject of the story itself. It is only at the end, the paper gone to press, that the exhausted night editor, grabbing a quick bite in an all-night diner, has time to understand "that Martin Luther King is dead and that I care."

Allen Ginsberg I had first encountered in another port city, Liverpool. As a journalist on the Evening Standard's "Londoner's Diary," I had been sent on an extramural trip to Liverpool to cover Ginsberg's visit to the home of the Beatles.

Allen's visit provided the occasion for a group of local poets to emerge from their dingy cavern on Canning Street, where they ran a smudgy little magazine called Underdog, and add a Liverpudlian dimension to the Beats. They included artist Adrian Henry, looking very surreal, Brian Patten, the clerical Roger McGough and Heather Holden.

Whatever happened to Heather? Women poets rarely got a look-in in those days, although Carol Ann Duffy, who would become Britain's first woman Poet Laureate, must have been somewhere in the Merseyside offing.

Having proclaimed Liverpool to be the centre of cosmic consciousness - and Liverpool having decided Ginsberg was really gear - Allen went on to Newcastle to say the same thing there, although it was left to a poet of quite a different ilk, Tony Harrison, to declare that Newcastle was Peru.

Ginsberg was in England after being declared King of May in Communist Prague. His happy knack was to create or validate a joyous counter-culture wherever he went. Just the person we needed in slumbering Saint John.

Presiding over the new Saint John branch of the university was a high school principal who, though game, was left rather gobsmacked by our wide-ranging plans. But, as former principal of the local academic high school, he had excellent contacts throughout the city.

The day before Ginsberg's scheduled arrival, the principal was tipped off that the Immigration authorities at the airport were going to refuse entry to the dissolute American poet. We should cancel hotel and hall bookings without delay.

King's County had a Progressive Conservative M.P. named Gordon Fairweather. A fair weather Tory, but a foul weather progressive.

Without delay I telephoned him. He came off the curling rink and promised to have a telegram in my hands within the hour from the Minister of Immigration. All I had to do was swear – so help me God - that while he was our guest Allen would not do drugs or corrupt the youth in any way.

After the meeting in the graveyard, I walked Allen across the old sea-faring town. We went down the hill to the waterfront past the City Market with its Dickensian figure of a flower-seller at the gate. Lamb the butcher. Pipes the organist. A law firm called McKelvey, Macaulay, Makem and, yes, Fairweather. The names required no Dickens to make them up.

Eventually, we reached the New Brunswick Museum. Ginsberg was delighted by a notice advertising an exhibition: Secrets of the Deep - Upstairs. He was even more delighted by the reception he received upstairs from the Archivist, Mrs Robinson. Oh, she said on being introduced to him, "Aren't you the son of Louis Ginsberg? He's my favourite poet."

Having walked across the decaying city, Ginsberg claimed that had he been born in it he would never have left. That was true of so many of its natives but when Ginsberg read his hallmark Howl later that evening to a hall full to overflowing it flushed out of the woodwork an assortment of local eccentrics few of us had imagined existed. "I have seen the best minds of my generation destroyed…"

One urbane colleague claimed that Ginsberg should have been a cantor in the Catskills. Possibly also in the Himalayas. Crowded into our cottage after the reading, our students listened wide-eyed as Allen and Chanchi discussed and sung – to the accompaniment of Allen's finger-cymbals - Indian and Tibetan chants.

In his turn, It was Allen who looked wide-eyed when our baby daughter, in her cot in the next room, was awakened by all the sound. Why, he asked, is the child crying?

John Drew's writing appears from time to time in The Daily Star and Bengal Lights.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments