Of 1971, 2024, Rabindranath Tagore and Martyred Intellectuals Day

Fifty-three years is a long time—long enough for memories to fray, for many details to be lost, and for even those that endure to begin to fade.

I say this because December 14th is upon us once again. In the changed circumstances of our country, some may need to be reminded of what this day means in our national context.

Fifty-three years ago, from the 10th to the 15th of December, 1971, some of the best and brightest minds of this land—teachers, journalists, medical practitioners, litterateurs, thinkers—were extinguished by the Al-Badr and Al-Shams collaborators of the marauding Pakistani army. While this process of intellectual killing began when the rulers in West Pakistan declared war on their fellow citizens in the erstwhile East Pakistan—the first teachers were killed on the Dhaka University campus on March 25th, and more than a thousand intellectuals were murdered over the course of the nine-month war—approximately two hundred were abducted from their homes on December 14th, taken to specific locations in the city where they were tortured, and ultimately killed, just hours before the liberation of the country on December 16th.

Why were they killed? The obvious explanation might seem to be that they were political opponents of the ruling Pakistani regime and their local sympathisers. However, this was not the case for all of the martyred intellectuals. I was reading the autobiography of the eminent philosopher and essayist Sardar Fazlul Karim, Atmojiboni o Onyanyo, the other day. He notes that some of the most prominent intellectuals who were murdered in 1971 were not active in the political arena. He mentions Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta, the eminent Professor of English at Dhaka University, who was shot by the Pakistani army on March 25th and died of his injuries on March 30th. He also refers to my father, Mufazzal Haider Chaudhury.

My father was a teacher of Bangla language and literature at the University of Dhaka. He never participated in active politics in the forty-five years he lived until he, too, was abducted by the Al-Badr, tortured, and murdered on December 14, 1971.

The obvious question that arises is: Why were people like my father and Professor Guhathakurta, as well as figures like Professor Munier Chowdhury, the famous playwright and educationist, who had been involved in leftist politics in his youth but had not been politically active for decades, identified as enemies by the collaborators of the Pakistani army? They were not political opponents. Why were they seen as such threats that they had to be eliminated?

The answer is this: Each of these gentlemen, along with the majority of other intellectuals who were martyred in 1971, had a vision for their country that was non-sectarian, secular, embracing diversity, and rooted in the rich cultural and ethnic heritage of the Bengali people. It was because the ideas they espoused were considered dangerous by the Pakistani rulers and their collaborators that they were marked as enemies. To the extent that, faced with certain defeat in a matter of days, the Al-Badr and Al-Shams planned and carried out their massacre as a final, desperate act. This was their attempt to cripple the emerging nation of Bangladesh.

In July and August 2024, we witnessed another mass movement emerge victorious in Bangladesh. This time, as on so many other occasions, it was the students of public and private universities who stood up against a regime that had come to embody an oppressive, kleptocratic oligarchy; a regime that had resorted to unconscionable, murderous tactics to suppress the rising tide of rebellion. Just as in 1971, this movement has had its martyrs: gallant young men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice for their cause.

These are different times, however, and in some ways, these young people see the world through different lenses than their predecessors. In particular, since the ousted regime sought to justify their wrongdoings by commodifying the amorphous 'spirit of the liberation war' and professed to be secular while nurturing sectarian elements within their own ranks and in society at large, today's young revolutionaries seem to have an instinctive distrust of those who claim to be secular and invoke 1971 at every given opportunity. It is this unease that I believe we saw reflected in many of the events that followed the movement, with talk of replacing the national anthem, wholesale rewrites of the constitution, and so forth. If they had their way, some would even change the flag of the nation or rename the country altogether, it seemed.

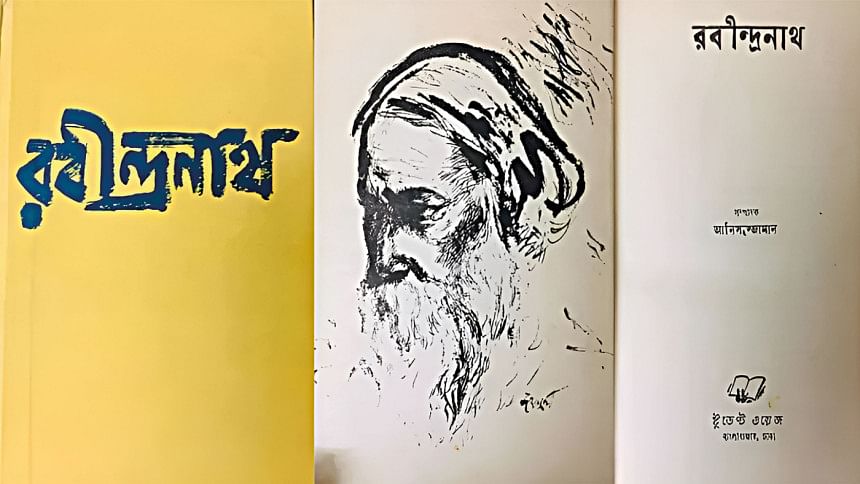

I found some of the arguments for replacing the national anthem particularly intriguing. Some claimed that Rabindranath Tagore, the writer of 'Amar Sonar Bangla', was not Bangladeshi, blithely ignoring the fact that the Tagore family has ancestral roots partly in Jessore and that the great man composed many of his enduring works at their family property in Kushtia (not to mention the fact that he passed away in 1941, long before Bangladesh came into being or India was even partitioned). They argued that the song was too pastoral and did not invoke the martial spirit within them. Well, my young friends, I wish I could have told them, it is a pastoral song for a pastoral people. It reflects who we are, which is why it resonates with so many of us.

I think many in this generation are simply unaware of the iconic value of Rabindranath Tagore, or the deep-seated, unwavering reverence for the ideals we fought for in 1971, or the uncompromising dedication to the concepts of inclusiveness, non-sectarianism, and secularism that an overwhelming majority of their predecessors hold in their hearts. They do not know that the autocrats and despots of a different time, such as the Ayub Khan government in West Pakistan and Monem Khan, the Governor of East Pakistan, sought to ban Rabindranath's songs in this land in 1967, only to fail. That 'Amar Sonar Bangla' was sung in Mukti Bahini camps across the land in 1971, giving the valiant young women and men fighting for the survival of their land the inspiration and steely resolve to soldier on until victory or death. So, it seems, that pastoral tune did its bit to instil the martial spirit as well.

They do not know that in the final moments of my father's life, he was asked by the Al-Badr assassins if he had written on Rabindranath Tagore, as if to do so would be a sin. An eyewitness, who was the only survivor from that wretched day, later testified that my father said he had. He looked death in the eye and said he wrote on Rabindranath.

This is the price that people in this land paid for loving Rabindranath. For holding on to our cultural heritage. We will not negotiate on this, nor shall we compromise.

These young people, who must surely love this land as much as my father's generation did, as our generation does, need to know these things. And if we all love this beleaguered, intrepid land so much, this country soaked in the blood of our martyrs, surely we can find common ground. Surely December the 14th will forever endure in our hearts as a day, in equal parts, of profound sadness and overwhelming pride.

Tanvir Haider Chaudhury is the younger son of Martyred Intellectual Mufazzal Haider Chaudhury. He is the CEO of Kazi Food Industries Ltd.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments