A Loss That Still Haunts Bangladesh

"Knock! Knock!! Knock!!! Sir, please come outside, we need to talk."

On the night of December 14, 1971, a sinister knock echoed on the doors of 1,111 homes in Bangladesh. The question "Who is it?" from inside was met with a simple yet chilling reply: "Please come outside, we need to talk." That was the last time these 1,111 individuals would step out of their homes. They never returned to their loved ones. It's not just a phrase but a symbol of a calculated attempt to destroy a nation's future.

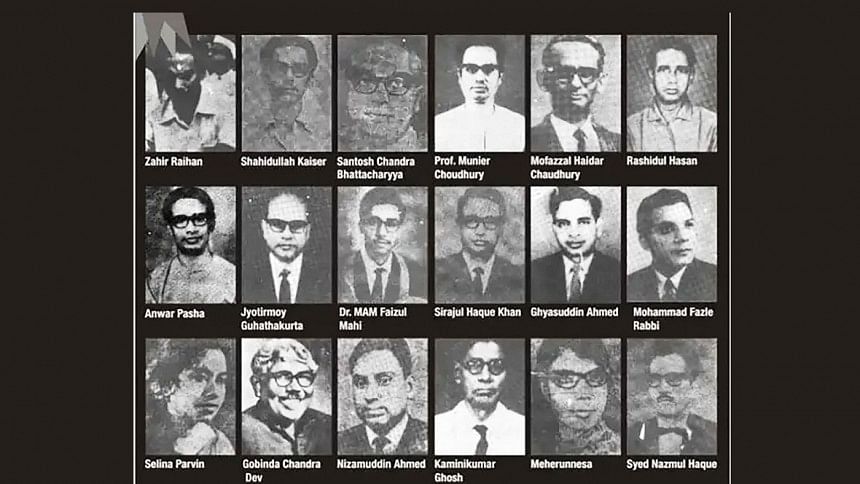

Today marks the 53rd December 14 — Martyred Intellectuals Day in Bangladesh. On this day in 1971, when the country stood on the brink of victory in the Liberation War, Pakistan's military, with the help of local collaborators, executed a ruthless plan to eliminate the nation's brightest minds. Teachers, doctors, journalists, writers, artists, and lawyers — the intellectual class who could guide a newly independent Bangladesh — were systematically abducted, tortured, and killed.

Among the 1,111 martyrs, 991 were teachers, 49 were doctors, 42 were lawyers, 13 were journalists, and 16 belonged to other professions. While their professional identities are well-documented, their political ideologies are often overlooked. Notably, most of them leaned towards leftist politics, which is not surprising. True intellectuals, much like white blood cells in the human body, serve as society's natural defenders against injustice. Historically, left-leaning individuals have been more inclined to challenge the status quo, while those on the right have often prioritised personal or religious interests over broader national concerns. This reality was evident then and remains so today, although the left has since become fragmented and divided into multiple factions.

The question arises: Why did the Pakistani military, along with local collaborators, target so many educators on the eve of Bangladesh's victory? The answer lies in the inherent power of education. By default, teachers are critical thinkers and vocal critics of injustice. The enemies of Bangladesh knew that to cripple a newly independent nation, they had to destroy its intellectual backbone. Killing teachers meant weakening the future generation's ability to rise, resist, and rebuild. It was a brutal yet calculated strategy — and, in many ways, it succeeded.

The Lasting Impact: A Nation Crippled by Intellectual Void

If we look at Bangladesh today, it is evident that the void left by the massacre of intellectuals has not been filled. Corruption, moral decay, and unethical practices have become rampant. The country's moral compass seems broken, and our ability to produce "true humans" has diminished. This isn't surprising, as we have failed to restore the intellectual foundation that was shattered in 1971.

UNESCO prescribes that at least 20% of a nation's total budget should be allocated to education. In Bangladesh, it's only 10-11%. Given our unique context — the brutal loss of intellectuals and the need to rebuild our society — we should be investing at least 30% of the national budget in education. Bangladesh lacks natural resources like oil or minerals, but it has something far more valuable — human potential. However, that potential will remain untapped if we don't nurture it.

The potential of humans is limitless if they are given the right guidance and education. But instead of building "true humans," our education system is churning out "false humans" — individuals who lack moral integrity, creativity, and the ability to think critically. This is evident in the rise of corruption, fraudulent schemes, and the plundering of natural resources like the Sundarbans. The Rampal coal power plant project, which threatens the environment, is a glaring example of this moral degradation.

The Consequences of Neglecting Education

The murder of Bangladesh's finest educators in 1971 was not just a physical genocide; it was an attack on the nation's intellectual capacity. The effects are still visible today. Think of the martyred educators as "master craftsmen" of human development. In their absence, we are struggling to build a society of thoughtful, skilled, and moral citizens. The British colonial rulers destroyed the art of muslin weaving by cutting off the weavers' thumbs. In 1971, the same was done to our education system. But this time, the "thumbs" of our master human-builders — our teachers — were severed.

Today, we continue to "kill" our educators, not with guns and bullets but through neglect, disrespect, and underfunding. The salaries of primary school teachers are abysmally low, treating them as third-class government employees. How can we expect excellence in education when those tasked with building the minds of our children are treated with such disregard? The same applies to college and university teachers. We continue to fail them, and in turn, we fail our students.

Brain Drain: The Silent Exodus of Talent

Since 1947, Bangladesh has been experiencing a "brain drain" — the departure of its brightest minds to other countries. Every year, thousands of talented students leave for higher education in the US, UK, and Europe. How many of them return? Very few.

Why don't they come back? Because the system has no place for them. Even those who want to return are met with bureaucratic hurdles and a lack of employment opportunities. The system treats them as outsiders, as if returning to serve their homeland is a crime.

Instead of welcoming them, we close the door on them. The message is clear: "Stay abroad, we don't need you." But the reality is that we do need them. The loss of these potential intellectuals is a tragedy in itself. Without thinkers, innovators, and scholars, how will Bangladesh develop the next generation of policymakers, teachers, and scientists? There is no government policy to bring these intellectuals back or create opportunities for them. If this trend continues, where will Bangladesh's future intellectuals come from? Without thinkers, researchers, and teachers, who will lead us to prosperity?

Why Not Welcome Foreign Faculty?

One way to fill the gap in our intellectual ecosystem is to recruit skilled foreign educators. Foreigners work in nearly every sector in Bangladesh — health, banking, and business — but not in education. Why? Imagine if our universities had professors from globally renowned institutions. It would create a competitive academic environment, pushing local teachers to improve their research, teaching, and engagement. Students would benefit from exposure to diverse perspectives, languages, and cultures.

Many top universities worldwide have an international faculty base. This gives students a "global education experience" even if they never leave their country. But in Bangladesh, university regulations require faculty to be Bangladeshi citizens. This is a restriction that serves no purpose. It is time to remove this policy and open our universities to skilled educators from abroad. If we truly want to create global citizens, we must give them access to global teachers.

Are We Witnessing a "Silent Genocide" of Intellectuals Today?

In 1971, intellectuals were dragged from their homes and killed in a single night. Today, we are killing our intellectuals slowly, over decades. By underfunding education, offering poor wages to teachers, and failing to recruit top talent, we are silently "killing" the future of Bangladesh.

Look at our schools, colleges, and universities. Are we producing independent thinkers, critical analysts, and problem-solvers? Or are we producing rote learners who simply memorise and regurgitate information? Our schools are like factories — but instead of producing innovative minds, they are churning out "flawed products" with no critical thinking abilities.

Our education system prioritises exams, certificates, and grades — not real learning. But real learning requires visionary educators, the kind of teachers we lost on December 14, 1971. Today, we continue to produce mediocre minds because we have failed to restore the legacy of those intellectuals.

Kamrul Hassan is a professor in the Department of Physics at Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments