Shilalipi: A Legend Carved in Stone

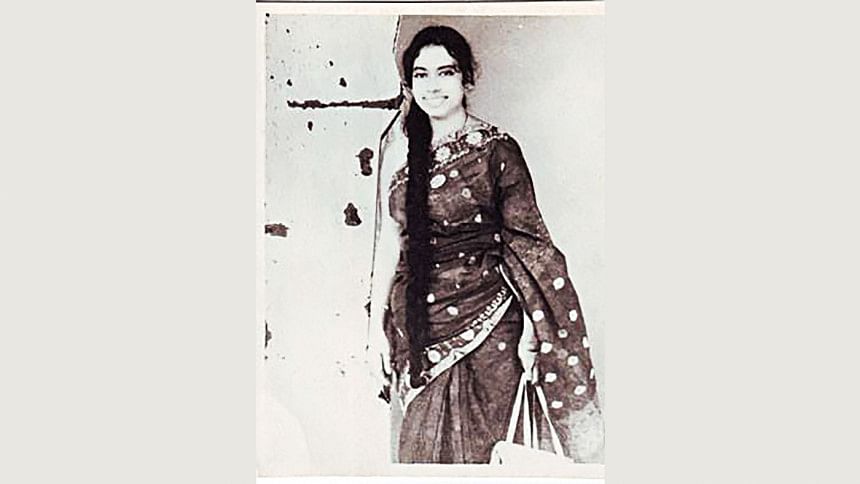

The film Shilalipi, directed by Shameem Akhtar, is a fictionalised version of the life story of Shahid Selina Parveen, a writer, poet, and magazine editor who was picked up, tortured, and killed by collaborators of the occupying Pakistani army during the war of 1971. Her name, therefore, shines as one of the Martyrs of the Bangladesh Liberation War. Shilalipi is a film that captures both the milieu in which the voices of protest were being articulated by the Bengalis of East Pakistan against the ruling military junta of Pakistan, as well as the intensely personal life struggles of a woman fighting for her individuality. It is, therefore, a deeply political film attempting to link the personal with the political.

Selina Parveen (screen name: Nasrin) is portrayed as a middle-class woman striving hard to eke out an income for herself and her eight-year-old son, Sumon (screen name: Suborno). In her day-to-day struggle, she takes up proofreading for a publishing firm and takes shelter in a rambling old building in Old Dhaka, where she and her son receive the fatherly love and care of Asad Bhai, and the intimate mothering of their Muslim and Hindu co-tenants. The gaunt, graying stones of the massive house are filled with the sights, sounds, and smells of warmth, comfort, and good cheer. But the distant thunder rumbles deeply, forecasting stormy weather. The voices of anti-Ayub protesters spill over the high walls, sometimes lighting the faces of the inhabitants of the house with anticipation and hope, sometimes spreading shadows of doubt and fear of the ominous.

The onset of the Pakistani military crackdown changed the situation almost overnight, transforming the carefree, breezy gait of the inhabitants into the measured stealth of their steps and the lowered voices. Ominous changes took place. Some tenants left for safer shelters, others were forced to leave for fear of being identified as 'Indian infiltrators', a nomenclature commonly reserved by the Pakistani state for those not identifying themselves with the defence of the structural integrity of the Pakistan state. Ultimately, Nasrin was left alone with her eight-year-old son, resisting pleas to go elsewhere. On top of this, she was sheltering freedom fighters in her house, thus putting herself in a dangerous position. Having lost a brother in the war, these were her brothers whom she could not forsake. As one tenant after another left the house, they left behind their presence in the mind of eight-year-old Suborno, a boy who had learned to bid farewell far too early in life.

On an early December morning, the chilling event came that was to tear his mother away from Suborno. Suborno was on the roof, imitating the fighters commonly seen amidst the blue, hazy clouds over Dhaka. The Indians had joined the war against Pakistan and had already taken command of the skies. Pakistani troops were surrendering to the joint command in outlying areas, and total surrender of the Pakistani forces was imminent.

It was during this time that bands of collaborators carried out Gestapo-like raids on targeted houses, blindfolding, binding, and taking away noted intellectuals and professionals of the country to camps where they were tortured and then taken to their deaths. Their decomposed bodies were later found in the brickfields on the outskirts of Dhaka city. But Selina Parveen, alias Nasrin, had never thought she had done anything great to warrant such a fate. She had been writing against the Pakistani state in her magazine and had been sheltering young Muktijoddhas (freedom fighters) at great risk, but she took these activities in her stride, thinking it was her duty to her homeland.

Separated from a husband who believed that the Party dictated everything, Selina Parveen's personal life was a struggle to attain her own selfhood. She therefore understood the sufferings of a nation experiencing that same pain and humiliation, and hence, helping it to stand on its own feet was a way in which she was helping herself too. Her sacrifice for the nation was not that she gave up her own life, but that she gave up the very things which had been at the root of her creativity: being a mother to her eight-year-old son and editing her own journal. The scene in which she was picked up by the collaborators, as seen through the eyes of eight-year-old Sumon, alias Suborno, is therefore spine-chilling. As she is led down the stairs by the collaborators, her son calls out to her. Her only reply is a tense and urgent "Ghorey Jao!" (Go inside). She repeats the phrase as they blindfold her and tie her hands behind her back, but with her head held back, looking at where her son must be at the top of the stairs, she tries to prolong her 'gaze' through her blindfold as she is finally dragged away. This memory is etched into the hearts of every viewer, as it must be in the heart of Sumon.

The whole story is narrated through the eyes of Sumon, who has grown into a young man carrying the pain of losing both his father and mother (he claims that his mother was both to him) at a tender age. His friend encourages him to research and write about his mother. They begin to visit old friends and acquaintances of his mother, exhibitions of 1971, and the story unfolds through flashbacks. As an introduction, the real Sumon speaks a few words about his mother and his memories of her, stating that this film is a way of paying homage to Selina Parveen, who is not only his individual mother but whose life and struggle are part of the creation of Bangladesh.

The film ends with Suborno (the fictionalised version of Sumon) and his friend viewing the monument for the martyred intellectuals in the killing fields of Rayer Bazaar, where Selina Parveen's body was found. The foundation stone laid by Projonmo '71 poses a question to all who visit there: "Tomra ja bolechhiley, bolchhey ki ta Bangladesh?" (Does Bangladesh say what you had said?). The song in the background, written by Shamim Akhter and sung and lyricised by Moushumi, accentuates the loss, struggle, and sacrifice of individuals such as Selina Parveen and adds grace to the visual imagery, which can only be compared to that of a flute playing amidst the swaying green rice fields of Bengal. It is a scene whose sights and sounds linger in the memory of a viewer long after the film is over.

The effectiveness of the film lies largely in the creative imagination of the director and the sincere and hard work of most of the actors. The film, being Shamim Akhter's second (the first being Itihash Konnya: Daughters of History), shows signs of the director's maturity in laying out her story with ingenuity.

Needless to say, the contribution of the actors to the film has been immense. The acting of Sara Zaker as Selina Parveen, Asaduzzaman Nur as her friend, Manosh Chowdhury as the grown-up version of Sumon, and Jishnu Brahmaputra as the young version of Sumon has been exemplary. They have given their all to portray what must have been, for them, a singular opportunity to give vent to those sublime emotions which go beyond any rhetorical understanding of 1971.

From fear to elation, from outrage to suppressed anger, from pain to the practicality of survival, from courage to sheer desperation, the full spectrum of emotions has flitted to and fro across the celluloid realities of Shilalipi, making it not only a story of a nation or an individual but rather a story of the human condition.

Like any human situation, no doubt, the film has its share of technical flaws and limitations, but that is not what is foremost in the minds of the viewer after watching the film. As in any work of art, it takes one down to the essence of human emotions, while at the same time elevating the soul to a plane where one feels as though one can see eternity, or rather, things eternal, like love, pain, beauty, and understanding. Shamim Akhter has taken bold and courageous steps in this direction, and one looks forward to seeing more of her work in the near future.

Meghna Guhathakurta is a former professor at Dhaka University and the daughter of martyr Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments