Shoemakers mend the fate of the northern poor

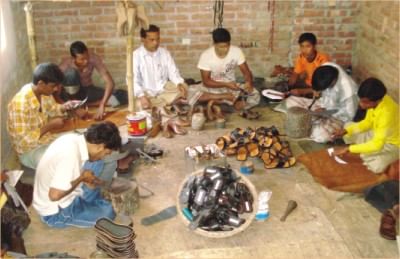

Labourers are seen at work at Kanij Shoes Factory in Kaluhati Purbopara Crossing of Charghat upazila, Rajshahi. Photo: Anwar Ali

Once farmers or day labourers, they all struggled to make ends meet. That is when a group of entrepreneurs of Kaluhati village in Rajshahi decided to break free from the clutches of poverty and venture into shoemaking, bringing about a silent revolution in the village.

The entrepreneurs, mostly young, admitted that they had always considered shoemaking a lowly profession.

With little or no education and professional qualifications and a small working capital, the sandal makers of Kaluhati have changed the scenario of the area completely. They have emerged as a successful cluster of businessmen.

Kaluhati, a densely populated village on the river Padma, is 20 kilometres away from Rajshahi city, a divisional town. The village of 12,000 is close to the Indian border. It is under the Nimtoli union of Charghat upazila.

The villagers in the area are mostly illiterate small farmers and day labourers.

The social background of the footwear business owners in the area does not reflect any artisan roots, as is usually seen in other cases. Traditionally, this business belongs to the low-caste Hindus.

The situation has now changed in Kaluhati. Members of the local elite are now engaged in this business. Many entrepreneurs between the age of 30-35 years are joining the band in the clusters.

Mamunur Rahman, assistant general manager of SME Foundation, who paid a visit to the village, said they have virtually brought upon a silent revolution. "It has played an important role in alleviating poverty in the area. Some artisans have become owners."

"I began my career as an artisan at a small footwear firm and later set up my own shop," said Moksad Ali, a successful entrepreneur of Kaluhati.

Rahman said many have emerged as entrepreneurs from artisan like Ali, who were day labourers before. “Now, they raise their voices in society too and have created employment for other villagers.”

A small group of unemployed youths in the mid 1980s decided to set up a small footwear firm with their own capital and labour. Two of them had some experience working as artisans at a footwear factory in Dhaka.

It was the initial success of this group that attracted others in the village. Over 400 labourers are now directly engaged in this industry, with another 1,500 to 2,000 indirectly.

Workers in the industry are categorised into three -- sole man, upper man and fitting man. A group of suppliers have also emerged, who provide raw materials and components. Similarly, some agents take the products out to distant markets for sales.

A semi-skilled labourer earns Tk 200 to Tk 300 a day, while skilled labourers make up to Tk 500-600. Working from dawn to dusk, a shoemaker can produce at least one dozen sandals. A small firm with family labour can produce up to 3-4 dozens a day.

A medium-sized firm with 10 employees manufactures 10-12 dozens a day. An average-sized firm produces about 120 pairs. In the peak season, about 1,000 pairs are produced at Kaluhati everyday.

Seasonal workers also contribute in the peak season, beginning three months before Eid-ul-Fitr and again two months before Eid-ul-Azha.

Factory owners or traders collect raw materials from Dhaka, particularly from the tanneries in Hazaribagh. Small shops get their raw materials from the larger ones or traders in the village.

The Kaluhati artisans basically produce sandals of about 20-25 types, made of leather and rexine. Prices of these sandals range between Tk 85 and Tk 500.

Some brands have also evolved, creating a niche in the northern Bangladesh markets.

Mamunur Rahman said these shoemakers should be given an opportunity to visit the big names in the industry, so that they can compare their products and learn. Banks should also need to take their financial products to them to help them grow.

Though the artisans do not produce shoes yet, they hope to do so with adequate financial, technological and infrastructural support in the near future. Manufactures say the local demand of the products is good and it is increasing gradually, as prices are competitive.

Some entrepreneurs are also thinking about creating their own brands. Kaniz, National, Kazal, Mannan, Mukta, Bithi and Lucky are some smaller brands from the area. Factory owners are eager to popularise their brands at a national level but they have no idea on how to go about it.

With the production and sales of these competitively priced sandals in North Bengal, the entry and sales of smuggled Indian wares have diminished.

Two entrepreneurs have their own sales centres at the local Arani Bazar. Earlier, the factory owners had taken their ware to town for sales.

Hiring a qualified design master is expensive for any small firm. So, the small entrepreneurs lack designers and are unable to develop new designs. They mostly use the familiar, traditional designs, copying any new design that has just made a debut in the market.

However, frequent power failures disrupt their production. Some big firms use generators to address the shortage.

For loans, most entrepreneurs depend on friends, family, or local lenders and associations that charge high rates of interest. They face a dearth of finance as they fail to meet the conditions required to get credit from banks. Some NGOs, like BRAC, Grameen Bank and ASA, however, offer some help in this regard. A group of owners, with the support of a local lawmaker, recently got loans from Rajshahi Krishi Unnayan Bank.

Most artisans learnt the trade from other workers. As a result, they lack adequate skills in pattern cutting, pattern placement, selection of leather, fault analysis and so on. Simple but structured training could improve the quality of their work a lot, Rahman said.

On the other hand, some firms that have developed brand names, face problems with packaging. "We fail to attract customers due to our poor get-up. The not-as-good products of some big companies are securing market shares because of attractive packaging," said Ali, an artisan in the village.

The sector also faces setbacks in finishing, pattern development, product variation, training, quality control measures and stock management knowledge. A recent major threat is the emergence of Chinese footwear, flooding the local markets, the assistant general manager of SME Foundation said.

Artisans are aplenty in Kaluhati. By ensuring a minimun level of government support, Kaluhati can be developed as a regional hub in footwear manufacturing. It can create employment and eradicate poverty, added Rahman.

Nawshad Ali, owner of a brand, started making sandals in 1987 by investing a small amount of money. He said artisans in the area have limited incomes, as they cannot compete with the big companies, even though they produce quality products.

"We cannot improve and enrich our designs due to a lack of funds. We also lack skilled artisans."

He said the business is largely seasonal, confined to the two Eid festivals. "We need money before Eid to stock raw materials, but we cannot do so, and therefore, stay content with lower profits."

A shortage of power also hampers the business seriously, he added. "We do not have good roads that connect the village with district towns, so the big businessmen do not come here."

Mizanur Rahman, another manufacturer, said: "We have created a market in the northern region, but we need support from the government to expand the business across the country and abroad."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments