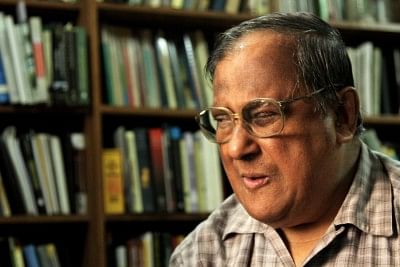

In Conversation With Akbar Ali Khan

Akbar Ali Khan, born in 1944, is known for his multiple roles in the service of the nation. His credentials speak of his professional and intellectual versatility. His pragmatic and, sometimes, outspoken views have been well received. A public administrator, member of the Mujibnagar government, former cabinet and finance secretaries, economist, teacher, adviser to caretaker government, former alternative executive director, World Bank, former Chairman, the Board of directors, Grameen Bank and author of some widely read publications, he is regarded highly as an intellectual and man of action.

(Shah Husain Imam and Ehsanur Raza begin The Daily Star monthly series of conversations with Akbar Ali Khan.)

The Daily Star (DS): You have seen at first hand the working of the Mujibnagar government. In fact, you were part of it. What specifically were your functions?

Akbar Ali Khan (AAK): My work with the Mujibnagar government can be divided into three stages. The first stage started before the Mujibnagar government came into being. This involved maintenance of law and order in Habiganj of which I was the SDO. In addition, when the Pakistan Army was reoccupying the areas and we were retreating, we arranged for the transfer of money from the treasury to the Mujibnagar government. I was instrumental in arranging transfer of 3 crore rupees out of the subdivision.

There were other officers who did so and that initially built the treasury of the Mujibnagar government. And then came donations from different provinces of India, but we could not convert the entire amount of Pakistan currency we took to India. We used to get them converted from Kabul. When the Pakistan government found that so much money had been taken away, they demonetized in 2-3 months. After 3 months' time, we could not change the currency anymore. So the entire money couldn't be used by the Mujibnagar government.

In the second phase, I moved to Agartala; we built up a regional administration under leadership of Hossain Towfiq Imam; established contacts with the politicians and the bureaucracy of India and also the Bangladeshi citizens who sought asylum in India and the freedom fighters. I worked for three months in Agartala.

Then I was transferred to the Mujibnagar government in Calcutta because at that time they were opening new ministries and there was dearth of officers. Initially, I was asked to work as deputy secretary, cabinet division and when the ministry of defence would be established I was posted as its deputy secretary. My work aside from the routine kind, was to provide supplies of various articles to Muktibahini through the Indian Army. For example, winter was approaching and there were not enough blankets. Now certain Muktibahinis, like Kader Siddiqui's bahini were not covered by the Indian government. There were a lot of freedom fighters who did not get enough assistance from the Indian government.

It's so funny that in those days there was no contract or tender, I was given the money and told to buy 5000 blankets from the market and take them to Fort Williams and find out where these are needed. One day, the defence secretary would come and say we are not getting news from the front so we should send some tape recorders to certain places. We then took money from ministry of finance, bought and sent out the tape recorders. I would assist the defence secretary and attend some of the interviews he held for recruitment of officers to Bangladesh Army. This was quite exciting and the workflow was not of normal bureaucratic nature.

DS: But it covers even the second question we had in mind. You've covered your part in relief work as well as war efforts. The next question I ask is whether the Liberation War was a revolution or an evolution?

AAK: This was a revolution but an incomplete revolution. It was not an evolution because we had to fight for our freedom, no one gave us independence. We won it through a very bloody armed struggle. We had to start it all of a sudden and we didn't have enough preparation or enough planning to do it; so it was more spontaneous than an engineered sort of thing. It was spontaneous uprising with a lot of ideas but then we found that many of these ideas vanished within three years of the coming of Bangladesh. That is why it is an incomplete revolution.

DS: Did you have to contend with any distractions from within?

AAK: It is known to everybody there were a lot of factions in the ruling Awami League at that time. There was a good deal of opposition from Khondker Mushtaque and his supporters. And even when we were working with the Mujibnagar government we found the differences between Khondker Mushtaqe and Tajuddin Ahmed and at one stage it was decided that Khondker Mushtaque would lead the Bangladesh delegation to the United Nations. When it was found he was in close contact with the Pakistan government and the American government, the decision was cancelled. In his place Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury was sent.

Immediately after independence, Khondker Mushtaque was removed from the position of foreign ministry and was given the charge of water resources ministry.

DS: To our knowledge, you like to be known more as an economist than a public administrator. If so, why so, given that you have been equally successful in both fields.

AAK: In public administration you cannot make any fundamental change. It is difficult in Bangladesh. In academic world you can come up with your own ideas and you can say, 'here I stand.' But in public service it is essentially a matter of compromise. No uncompromising public servant can survive. If he cannot survive, how can he contribute?

DS: What are your points of discontentment, if any?

AAK: You see, I have a general theory that I am finding true about most of the spheres in Bangladesh. It is this that in most cases the bad people are not punished and the good people are not rewarded. You cannot have a society functioning well if the bad are not punished and the good are not rewarded. The incentive system has broken down and this worries me very much.

DS: Do you have any silver bullet to overcome the problem?

AAK: There is no silver bullet because in the present system the current inefficiencies are guarded by vested interests and they would not like to concede any ground. So it is possible only when a reforming political leadership comes into operation; a man like Kamal Ataturk, then he can probably do something but ordinary politicians will not be able to do anything.

DS: There has been much experimentation with poverty alleviation. Your own thoughts.

AAK: You see, the most important thing about poverty is that it is multifaceted. The way I look at poverty is the way Tolstoy looked at unhappy families. Tolstoy used to say, all happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. The problem with poverty is that poor are not homogenous. They are heterogeneous. And there is no single solution for poverty. There will be innumerable solutions. I do not agree with professor Yunus that poverty will be consigned to the museum in the next 20 or 50 years. Because even in the most advanced countries they have problems of poverty but theirs are of a different kind than in Bangladesh. That's why I would think that we would have to use a lot of instruments and a lot of approaches. No single instrument or approach would work. That is why microfinance was criticised. It is one of the solutions of poverty, not the solution. At best it can address some forms of poverty but not all forms of poverty. When Dr. Yunus got the Nobel prize, everybody created the impression that you can solve all types of poverty by microfinance. I don't think Dr. Yunus would claim it would. It could solve the problem of say 40 percent poor of Bangladesh; there will be another 60 percent poor people for whom you would have to find other solutions.

DS: Rich-poor gap is widening, how do we bridge it?

AAK: This is not a problem only in Bangladesh, this is a problem of globalisation. And this is also increasing in the industrial countries. Real problem finds a resonance with the Bangla phrase: Dillir Laddu. If you have eaten it, you will repent. If you have not, you will also repent.

If everyone is equal, there is no stimulus for innovation. But if you allow inequality to grow, there will be so much discontent, it will be destructive. In this situation, the government will have to pursue a very balanced policy. You should not allow inequality to grow too big nor eliminate urge for self-development. You should pursue a pragmatic approach rather than an ideological approach. Ideology cannot give an answer to this problem.

DS: But economic injustice tends to affect human rights.

AAK: That's right. That is why we should collect higher taxes from the rich to help the poor.

DS: Your recommendations for effective aid utilization.

AAK: We have to have a stronger economic management in Bangladesh. The projects that are funded by donors are mostly selected by them. We don't own them.

You have to have a vision. You have to think what you need. Suppose you go to some secretary and ask him or the planning commission, I would like to give you so much money, what would you do? They would only be expanding the current programmes, not coming up with really new ideas. It was my experience during 10 years as secretary. No one does any thinking, everybody is busy doing his routine work.

If you cannot compete with the donors at par, then obviously you will be at a disadvantage. Our administration is not strong enough to talk to them on equal terms. For that you have to have that much knowledge and we have serious knowledge gap in our administration.

DS: Do you think the quality of public spending has improved over the years?

AAK: I don't think…

DS: There has been now a little bit of an inclination towards the poor…

AK: You see, there are two things: one, historically in Bangladesh there have been certain principles of economic management. Those principles have been encouraging agriculture, primary education, giving assistance to the poor, building rural infrastructure. So the same thing has continued. But the problem is, there is much scope for improvement in policy-making. It is not sufficient to allocate money for certain sectors, you have to ensure that the money is properly utilised. That is the real problem of public sector management.

DS: Your recipe for infrastructure development, why has the PPP not taken off?

AAK: On PPP my answer is very simple. First question is what sort of PPPs do you want? If you want PPPs for airport, if you want it for port or if you want it for overbridges, then you will get PPPs. But if you want PPPs for electricity or for building new roads, it will be difficult. If you can't give gas or you don't have oil, it is unlikely the good PPP investors will be interested in the power sectors. In the road sector our land acquisition system is so bad, that no one would like to invest money and wait to complete the projects in 20-25 years.

DS: Incidentally, we have not been able to rope in non-resident Bangladeshis in our development pursuits at all.

AAK: Here we have a problem. If you compare with India and China there are lot of non resident citizens who are very rich and can invest as entrepreneurs. But Bangladeshi non-residents are not a big community. It is very difficult to organise them and bring in the money. If there were large companies owned by non-resident Bangladeshis then it would have been easier for them to invest.

DS: In the present global economic clime, what can be done to enhance the prospects for RMG exports?

AAK: The issue is going into new types of RMGS. For example, if you go to a Singaporean tailor shop, about four years back I went to one and ordered for a suit and the whole shop was filled with boxes with addresses to Sweden and Norway. They were exporting suits. I found out most of the small shops were also exporting suits to European countries. The most expensive item in the garments industry is customised clothes. Because people don't want readymade off the shelf suits. They want suits that will fit them. If they send the measurements to Singapore and if those suit are made exactly to measure, by sewing one suit you earn much more than by running one small garment factory in Bangladesh. If you sell customised items you earn more money. So there are a lot of areas we have not gone into. We are still in the cheapest areas and the least mechanical areas. We need to look into areas where more skill is required.

DS: What are the prospects of coming out of this two dimensional export regime RMG and remittance?

AAK: I see prospects only because we have a lot of people working abroad and when they will be coming back to Bangladesh, I am sure, they will start to export things we didn't export earlier. People from Middle East came and started cap factories in Bangladesh. Then you see food processing. Now we have a lot of Bangladeshis exposed to the outside world and they know the outside market. If they take leadership, they can make a difference quickly.

DS: Where do you think we can break new grounds for exports in geographical sense?

AAK: Problem is if we aim at countries of our level their demand is very limited so that economic considerations dictate we should try to capture the markets of the industrial countries rather than those of developing countries. They will not be able to buy more goods. Even if you sell a small fraction to an industrial market the earning will be much higher than if you sold to a very big fraction of a developing market.

DS: As a high government functionary and as a World Bank official you have had the advantage of seeing development issues from both ends of the spectrum. Please share some of your experiences and insights.

AAK: Main problem I found is two-fold. One, the World Bank and other multilateral institutions are at times dogmatic. They are given certain policies and they try to push these, irrespective of the fact whether these will fit into the size of Bangladesh or not. There you have to be cautious. But then there are questions of reforms that must be sequenced in accord with when you can do certain things and when you cannot. To do that you have to have enough understanding of your own economy and the Bangladeshi side should be able to protect its own viewpoint.

The other side of it is if you do not agree with the donors it is not sufficient to say I do not agree with you; there should be counter proposal from Bangladesh. And in most cases I found there was disagreement but no viable counter-proposal. For example, we must be able to say we can't do what you say but we can do this in place of that. Here are three things we can do and please see which are acceptable to you. That is the way to go about it.

The main fault as I told you and as it was time and again emphasised by economist Stiglitz that these multilateral financial institutions try to further the agenda of the industrial nations irrespective of the fact whether they are good or not. For example, the way the IMF handled the crisis in Thailand and Indonesia, it was mostly based on theories and it caused a lot of problems for the people.

World Bank and IMF are not monsters nor are they angels. They have their limitations because they are funded by industrial countries and he who pays the piper plays the tune. What countries like Bangladesh will have to do is they will have to compromise, they will have to find out which policies they can manage and accept and that which are totally unacceptable. These things are not done in Bangladesh, these are better done by government in India which is why there is less friction between them and donor agencies.

DS: Looking at the reserve of talent in the government and the private sector, the think tanks, how would you rate our national negotiating capacity?

AAK: It is limited. I have to go back to the problems of the bureaucracy. The way how our bureaucracy is organised it is difficult to ensure merit. It has expanded like anything. For example when the British left in 1947, they had about 1000 ICS officers. I think in Bangladesh today we have more than 1000 deputy secretaries and joint secretaries. The problem is that you cannot train everybody, the resources are limited as are opportunities.

DS: The role of privates sector think-tanks?

AAK: They, I think, are doing well because private sector is doing well both inside and outside the country.

DS: As cabinet secretary you have closely seen from close quarters the working of one elected government or two?

AAK: Sheikh Hasina appointed me as cabinet secretary. I was cabinet secretary of the caretaker government. And then I was cabinet secretary of Khaleda Zia government.

DS: Basically, could you define the cabinet secretary's role?

AAK: Cabinet secretary's role in Bangladesh is more limited than in India or Pakistan. Because in India at one time the cabinet secretary had say over the intelligence activities of the country. What cabinet secretary does is to act as a conduit between the secretaries and the prime minister. If there are problems that the secretaries cannot bring to the notice of the prime minister, then the cabinet secretary can take it to the PM or arrange that. But it not possible to be successful in all cases. In some he can, but in many he cannot. There are inherent problems in Bangladesh bureaucracy and there isn't much you can do about that.

DS: But isn't political interference an impediment?

AAK: I can give you an example. With all the governments I have worked I found the officers who have been cleared by superior selection board for promotion would not be promoted, no reasons having been assigned. The decision was taken at the highest level. This is a thing that should not happen and I have personally pleaded many times that this should not happen. If someone is fit for promotion, promote him. But if you don't like him don't give him a good posting.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments