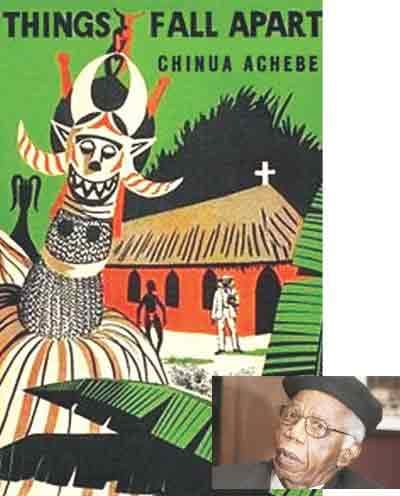

When Things Came Together: a book about a book

Chinua Achebe (Inset)

Some books are literally seminal. They generate so many other books. Things Fall Apart (TFA) is one such. It has become a modern classic, we know. And it's giving rise to so many other books also. At a place as far as Dhaka, a commemoration conference for Things was held in 2008, on the occasion of its 50 years. The Department of English of Dhaka University organized it. News of that conference and that Prof. Kabir Chowdhury spoke at its inaugural reached certain unexpected corners. And then one day Prof. Chowdhury called me over phone to say that one of his old acquaintances, Professor Don Burness in the USA, had got news of our Achebe Conference and sent him a letter of appreciation for all who had organized it. He mentioned me and some others by name in that letter. What was more enthusing is that through Burness, who happens to be a close personal acquaintance of Achebe's, the latter (Chinua) also had come to know about our conference. I was overjoyed; for anyhow it is I who took the initiative for this conference. I tried to share the joy with others by reading out Prof. Burness's letter at the Academic Committee meeting of the English Department. But a quite different surprise was still waiting for us. For Prof. Burness and some others had also organized a conference in Lisbon on the same occasion, and had sent us a copy of its proceedings, When Things Came Together. The other editors of that book are: Inocência Mata and Vicky Hartnack.

The University of Lisbon published it in 2009.

The section-divisions in When Things Came Together are: Opening Words, Keynote Address, Panel 1: On Things Fall Apart, Panel 2; Fiction in History, Panel 3: Achebe's Generation, The Lisbon Writers Panel in Dialogue with Chinua Achebe, The Conference Speakers' Bio-bibliographies and A Pictorial Display of Some of the Events.. We thus get some ideas about the book.

In the first section of "Opening Words," among other items, we get introduced to one of the keynote speakers of the Lisbon Conference, Niyi Osundare. He is a poet and prose-writer from Nigeria, but what distinguishes him more is his commitment to his people. What Inocência Mata said at the conference while introducing Professor Niyi Osundare is remarkable and rarely said nowadays, "Professor Osundare has rightly become one of the prestigious literary critics in Nigeria and Africa … He is a true "organic intellectual"(Antonio Gramsci) who has never backed down from his standing as a man of letters so as to lend his voice to denounce the restrictions imposed upon journalists and intellectuals and limiting their freedom of speech under his country's military regimes …" We come to know also how Osundare, a teacher at the University of New Orleans since 1997, suffered recently through the devastation of Hurricane Katrina there and lost almost his entire library. Inocência observed, "While "normal" people tried to save their belongings, he desperately fought to save his books. But being the optimist he is, he shrugged it off without any fatalism: no big deal. I am alive anyway."

There's a lot to mention about Osundare's speech titled "The Eternal Value of Things Fall Apart." The chief value it finds for the novel is how it initiated a new phase of true African literature. Osundare recounts how for a long time, Nigerian or African students were exposed to a set of textbooks that lacked in so many respects,

They proffered a setting, a universe of imagination, panoply of experience, a demography of characters, even a certain nuance of narrative and language that we found strange and familiar, quaint and curious at the same time. Their language is not that of our homesteads and marketplaces; their human population has a colour and custom not exactly our own. Their creators probably never knew about our existence. But somehow, something in them resonated powerfully with our common humanity, we wept with Lear on the heath, our hair rose with the horrors in Wuthering Heights, our ears throbbed with the plaintive notes of Keats's nightingale, we accompanied Gray as he walked through the graveyard and felt replenished by his moral meditations, while Wordsowrth's Tintern Abbey connected powerfully with our youthful sensibility, our will to growth.

But we felt there was something by us, about us, in us, that these works did not, could not articulate, despite their claims (or those of their critics and interpreters) to universality.

A longer recount coming from Osundare is also about what we so often tend to forget and underrate. One may only wonder what shame or guilt the West ever honestly feels over the situation of clear injustice and discrimination in knowledge, ideas, etc. Osundare recounts his young years, "Young as we were, we felt there was something wrong in a life spent singing other people's songs, reading other people's stories, studying and absorbing other people's historyas told by themwhile the very existence of our own was loudly denied." As I find it in Bangladesh, our latest tendency to forget is a result mostly of "Theory" in general and what Aijaz Ahmad particularly calls "Literary Postcoloniality." I shall like to explain by saying that the phase of Postcolonial Theory floated from the West by theorists like Spivak and Bhabha has disconnected us almost totally from the earlier phase of political postcolonialism initiated by Hamza Alvi, during the seventies. And present literary Postcolonialism was and is there rather to save the past and present colonizers.

The second keynote speech at the Lisbon conference, "The Narrator in the Contact Zone: Transculturation and Dialogism in Things Fall Apart", was presented by Joäo Ferreira Duarte, who teaches at the English Studies Department of Lisbon University Faculty of Letters and is head of the Comparative Studies Centre there. Duarte interprets Achebe's masterpiece in its similarity to a colonial Peuvian manuscript dated 1613, and he compares the narrator's position in the former with the novelistic trend called "post-Flaubert realism." He introduces the concept of "contact zone" for representing in case of Things, the "scenario where the stories of Achebe's characters are played out … with the first arrival of the colonizers…" This concept, he says, comes from Mary Louis Pratt, whom Duarte follows further into that of transculturation "which she considers a phenomenon of the contact zone and defines as the process by which 'subordinated or marginal groups select and invent from materials transmitted to them by a dominant or metropolitan culture." Duarte then refers to Diana Akers Rhoads to place some interesting information of glory about the society in the cluster of nine villages in Iboland that compose the setting of Achebe's novel, "… this society achieved what most people today search for: democracy, tolerance, balance of male and female principles, adaptability to changing circumstances, redistribution of wealth, effective systems of morality and justice, and memorable poetry and art".

It is in connection with the concept of transculturation, which is a phenomenon of "contact zone", that Duarte talks about the Peruvian manuscript, and that is perhaps the most attractive and interesting part of Duarte's keynote paper. Transculturation happens, he says, as an "outcome of negotiations that involve radically different systems of meaning and social status linked by relations of centre and periphery, authority and subjection." Mary Louis Pratt, in a 1994 essay, placed and analysed a neat example of transcultural production from colonial Peru, "the manuscript of La primera nueva coronica y buen gouierno, dated 1613 and signed by one Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, an Inca native from the Andean city of Cuzco.

But Duarte's main argument is that TFA "is a transcultural artifact through and through, the product of Achebe's reinvention of the novel form appropriated from the colonizer's culture and used for the purpose of Igbo representation (what Mary Loise Pratt calls autoethnography)." He brings in the Bakhtinian concept of dialogism also, for it "can help us grasp the role of the narrator in negotiating the complex set of representations that the colonial encounter triggers off." Towards the end, Duarte places for us a summary of his arguments in the paper:

…the novel form provided Achebe with the stylist apparatus realism and dialogismfor his project of Igbo auto-ethnographic self-representation. Furthermore, it is plausible to assume that Achebe is doing in the mid-twentieth century for the Igbo people pretty much what the Peruvian Guaman Poma did in the seventeenth century for the Andean peoples living under Spanish rule, namely, among other things, re-writing their respective histories. The difference is that Guaman Poma appropriated a historiographic genre for the purpose which Achebe did it through autoethnographic fiction; at any rate, both texts, regardless of their wide dissimilarities, could very well be labeled "counterhistory" or "adversarial history", terms by means of which scholars have pinpointed the historical hub of Things Fall Apart (Aizenberg, 1991; Begam, 2002:7)

Duarte quotes and analyzes at some length the final passage of TFA. He mentions the idea that in the nine-village community "things had begun to fall apart even before the colonial encounter speeded the process up." But, then, a more important question Duarte raises is: "Are we not just projecting onto the Igbo social structure conceptual tools that we have culled from western philosophy, ethics and political science?" His conclusion is that "transcultural texts are written in the present, from the present, for present purposes of resistance and critique," and that "bearing this in mind will help us acquire a fuller appreciation of what is perhaps the greatest masterpiece of postcolonial literature."

At the conference, Panel 1 discussion was jointly chaired by Ana Mafalda Leite, Faculty of Letters, University of Lisbon, and Inocencia Mata, Co-convenor of the conference. Stewart Brown from Birmingham University's Centre of West African Studies talked about "Things Fall Apart; poetry as counter-commentary, perhaps", indicating how Achebe's poetry and prose contain common and fundamental literary concerns. Don Burness, another co-convenor and late of Franklin Pierce University, USA made a sensational comparison between TFA and the fourth novel (1984) by Jose Saramago, pointing out the eternal nature of some of the phenomena manifesting through the ages and at various places of our planet. His paper is styled "Watching the Masquerade : "Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart and Jose Saramago's O Ano da morte de Ricardo Reis." To conclude, Don Burness writes as follows: "In our age writers from all over the world have reaffirmed that literature at its best is humanity's song of a better and more enlightened world. … Literature can enable different people to know each other. Maybe if we can really learn this, then just maybe we can create societies where things are not always falling apart". "Socio-Cultural Commitment in Things Fall Apart" was the paper presented by Bamisili Sunday Adetunji who had researched hard and placed a different viewpoint.

Panel 2 discussion focused on History in Fiction. The session was chaired by Manuela Ribeiro Sanches, who has been deeply involved in a research project titled "Dislocating Europe" running at the Faculty of Letters, University of Lisbon Comparative Studies Centre. The papers were presented by scholars coming from very different backgrounds and working in diverse fields. One such paper was from Nwando Achebe, Achebe's daughter, who spends time between Michigan State University and South-Eastern Nigeria, where she does a lot of research. Her paper, "Balancing Male and Female Principles: Teaching about Gender in Things Fall Apart", presents the issue of teaching African history to Western students with the help of non-Western materials like Things.

Chelva Kanaganayakam's paper is a comparative one; it places a comparison between the ethnic trouble between the Tamil minority and the Sinhala majority in Sri Lanka and the upheaval in Ibo community life with the advance of colonialism. Surprisingly, Sri Lanka's trouble came to sort of a head in the year Achebe's first novel was published; There are other coincidences in time and place though, and the case of Leonard Woolf, a British colonial writer is one such.

Fernanda Gil Costa's paper, "Can Fiction do it better than History? On Chinua Achebe and Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa" is a comparative study involving use of fiction to broaden Western understanding of African history. Pires Laranjeira's paper, Things Fall Apart: Change in the Ibo World", dismisses any idea of primitivism about Ibo culture, and claims the status of an extremely intricate and finely wrought system of values and practices for it. These values and practices deceived the European newcomers for their seeming ingenuousness and defended the cohesiveness of the traditional Ibo community.

In the last paper of the section, Jose Luis Pires Laranjeira has placed some drawings inspired on the impressive narrations that he found "extremely visual, dynamic and true-to-life" in TFA. He also mentions how TFA is fascinating for "several secondary stories within the main story, all mapping out simple although strong outlines which in turn are steeped in the history of the Ibos before and after the white man's appearance in their lands."

By skipping over a little, we find one very unusual section in When Things. Styled "The Lisbon Writers Panel in Dialogue with Chinua Achebe"; it presents Achebe speaking with the panelists from Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. This video interview took place in the Main Hall of the Lisbon University Chancellery. It was followed by a 30-minute discussion during which questions were put to the panel of writers who had joined Achebe at the video conference. When Things has an edited transcript of the conference and the discussion that followed.

And that brings us almost to the end of the book. The only thing that remains is "A Pictorial Display of Some of the Conference Events"sort of a photo album. This duly completes a book that can be considered a brilliant documentation of an exceptional meet of intellectuals in Lisbon to celebrate 50 years of a novel that wrote back in an irrefutable manner and sent others also to write back. Intellectuals are there more from the West to talk and write back against their own West. Nothing can be a surer proof of the true worth of the triggering text, Things Fall Apart.

Prof. Kabir Choudhury handed over When Things Came Together to me desiring that I write a review. (Prof. Burness had sent it to him.) I do that when he is no more to read it. I only hope that Prof. Don Burness is there to receive it when I send him a copy. For with my characteristic disorganization, I've not been in touch with him for a long time.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments