Child victims of July uprising: Of abandoned toys and unlived tomorrows

They were readers of fairy tales, keepers of marbles, chasers of kites across twilight skies. Some still asked to sleep in their mother's arms. Others, on the cusp of adolescence, had just begun to dream in the language of futures -- of stethoscopes, classrooms, galaxies. They were children, dreamers of careers, cartoons, and cricket.

Some were students with notebooks in hand. Others were street children swept up in crowds.

In the heat and fury of the July uprising, they died -- on streets, in alleyways, even on their own rooftops.

Bullets did not ask for age.

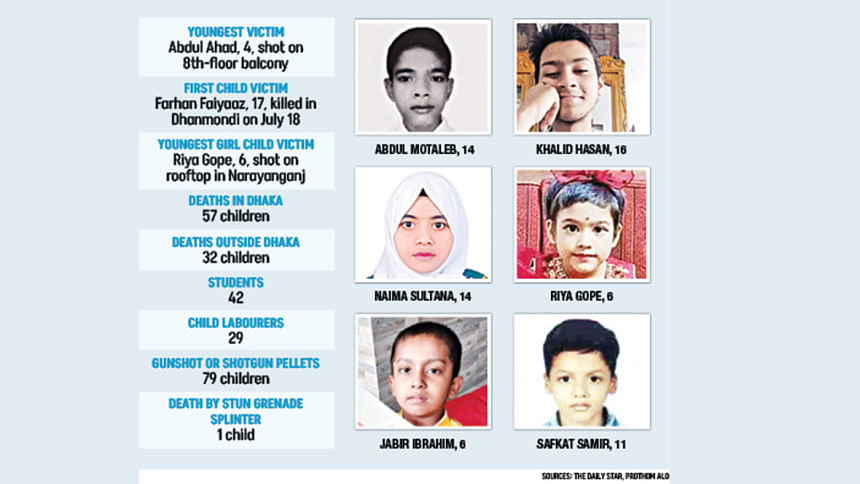

Official figures say 132 children died. The UN confirms that at least 118 children made up over one in every eight of the victims.

Each number hides a name, a dream, a future that now exists only in memory; each representing a shattered family and a nation mourning the true cost of the unrest.

Riya Gope

Six-year-old Riya Gope was one of the youngest to die. She was born after years of her parents' waiting -- on a December 24. She left this world on another 24th, in July last year.

On July 19, she was playing on the rooftop of their four-storey home when a bullet struck her. She held on for five days at Dhaka Medical College Hospital before her heart gave out.

"We miss her terribly. She was the centre of our lives, and the grief just won't ease," said her father, Deepak Kumar Gope. "Sometimes, when I come home, I still expect her to run to me. It feels like she's everywhere, yet nowhere. The house is so quiet without her."

The couple are now trying desperately for another child.

"I've asked other parents if the child they had after loss looked like the one they lost; if the faces match; if the smile is the same. If we're lucky enough to have that… maybe then, our broken hearts will heal a little."

But Riya's mother, Beauty Ghosh, continues to battle both gynaecological complications and trauma. They've packed away Riya's belongings in an attempt to ease the pain. Still, the silence lingers.

In March, the Sultana Kamal Women's Sports Complex in Dhanmondi was renamed the Riya Gope Women's Sports Complex in her memory.

"We heard about it," said Deepak. "But nothing feels important anymore when our daughter isn't here."

Jabir Ibrahim

Six-year-old Jabir Ibrahim, the youngest in his family, was killed by police during a rally celebrating the fall of the government on August 5 in Uttara.

Jabir loved his birthday. May 19 was his favourite. He would scrawl it everywhere: on walls, notebooks, even on his hands. Since his death, his family no longer celebrates birthdays.

"Every birthday felt like Jabir's. He always cut the cake, even on his siblings' birthdays," said his mother, Rokeya. "Last month was my daughter's birthday, the month before was Jabir's, but we did nothing. It feels like birthdays don't exist anymore."

He was a picky eater, and Rokeya spent her days worrying about what to cook so he would eat. "Now I just lie in bed. There's no one left to feed," she said.

She spends hours looking through his photos, especially one taken minutes before he was shot, where Jabir holds up a victory sign. She's kept everything: his Spider-Man bag, his bicycle, his books, toys, and the bloodstained trousers he wore that day.

His father, Kabir Hossain, now lives among memories. He shares them online, unable to move past the weight of a loss too large for words.

Abdul Motaleb

The same grief weighs heavily on Abdul Matin and Jesmin Begum, parents of 14-year-old Abdul Motaleb, known as Munna.

An eighth-grader last year, Munna was shot near Jigatola and later found dead at the central Shaheed Minar, where students carried his body in a solemn procession.

"My son was kind-hearted, always ready to help others," recalled Matin, a tannery worker. "I told his mother not to let him go out during protests; if needed, to keep him tied at home."

"On the day it happened, we had lunch together. I saw him resting, but after I left for work, he went out to join the protests, and was shot."

Munna didn't have a phone. After the pandemic began, he used his father's for online classes and made a few TikTok videos.

"When the pain gets too heavy, we watch those videos," said Matin.

Birthdays in their conservative family were simple. Munna would bring his own cake and share it with everyone. But last December, his birthday passed in silence -- no cake, no celebration.

Even Eid, the day of joy for Muslims twice a year, has become a reminder of Munna's absence. During Munna's last Eid-ul-Azha, Matin found him at the cattle market in a volunteer's uniform, helping buyers.

At first, Matin felt angry -- who had told him to do this? Was money so tight that Munna needed to work?

But Munna explained he wasn't there for money, only to spend time with friends and help others while school was closed.

"This year, at the cattle market, I found myself searching for Munna, even though I know he's gone," Matin whispered, his voice heavy with grief.

But grief is not the only burden these families carry. The pursuit of justice has become yet another endless road, filled with uncertainty, bureaucracy, and silence.

Some parents tried to file cases, only to be turned away or discouraged. Others managed to open cases, but there have been no arrests, no updates, no accountability.

Deepak, for example, never intended to file a case. "What would we have gained? Our daughter is gone. Nothing can bring her back," he said.

However, on July 1, around 11 months after Riya's death, police filed a case against up to 200 unidentified individuals, allegedly affiliated with the Awami League and its associate groups.

Meanwhile, Munna's father, Matin, said they filed a case at Dhanmondi Model Police Station but have no idea about its progress.

"Sometimes the police call to check if we are facing any threats, but other than that, there is no update," he said.

Jabir's mother, Rokeya, also informed this correspondent that although they filed a case against the personnel of Uttara East Police Station, the perpetrators remain absconding, and there have been no updates.

Safkat Samir

In the case of 11-year-old Safkat Samir from Mirpur-14, shot in the eye while closing a window on July 19, the bullet pierced his skull and exited, killing him instantly.

His father, Sakibur Rahman, said he was summoned to Kafrul Police Station that night through a local Awami League leader, where he was initially pressured to sign a statement saying he did not want to pursue a case.

Later, following extensive media coverage, the police compelled him to file a first information report on the condition that Safkat's body would not be exhumed from the grave.

However, a fraudulent group then persuaded Sakibur to file another case in court against some prominent Awami League leaders. It was later discovered that the accused in that case included the names of two of the group's rivals in a property dispute.

Although Sakibur appeared in court eight times and submitted affidavits stating that these men were not involved in his son's death, one innocent man was jailed for five months before being released on bail.

To date, there has been no progress in identifying or prosecuting the real perpetrator responsible for Safkat's death.

Many children remain uncounted

But these deaths are only part of the tragedy. Many children were never counted, while countless others now live with injuries and silent wounds and trauma from what they saw and whom they lost.

"We don't even know how many street children died," said Child Protection Specialist Gawher Nayeem Wahra. "No one tried to find out, because children simply aren't on our agenda."

Wahra noted that survivors often saw violence firsthand and now need counselling and safe spaces to heal.

"Children hold memories deeply. They can recover, but only if given space. Schools, TV programmes, and families offer nothing to help them heal," he said.

He also warned against involving children under 18 in politics, especially with the election approaching. Without careful protection, more children could lose their lives during turmoil.

But beyond warnings and statistics, for the parents left behind, every sunrise is a reminder of what was lost. And every silence echoes with the laughter that won't return.

Leafing through Jabir's unfinished notebooks and the award he received at his last art competition, his mother Rokeya whispered, "If this country cannot protect its children, then what future are we even fighting for?"

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments