NHRC yet to be reconstituted seven months on

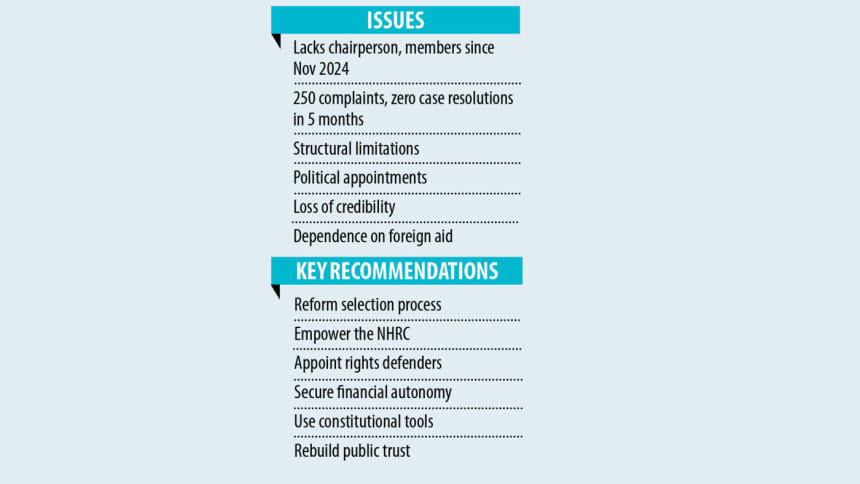

More than seven months after the resignation of its chairperson and members, Bangladesh's National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) remains leaderless, powerless, and largely ineffective.

Following the fall of the Awami League government and amid criticism that its leadership was politically appointed, Kamal Uddin Ahmed, a former secretary, stepped down as NHRC chairman on November 7 last year.

Full-time member Md Salim Reza and honorary members Tania Haque, Prof Biswajit Chanda, Kongjari Chowdhury, and Md Aminul Islam also resigned.

Another member, Kawsar Ahmed, resigned earlier.

They had all been appointed in December 2022 for a three-year term.

The NHRC, established under the 2009 Act, was aligned with the 1993 Paris Principles to function as an independent rights watchdog.

These principles require such institutions to be autonomous, well-resourced, and capable of investigating all rights violations, including those by state actors.

Since the leadership stepped down, the NHRC, once envisioned as the nation's human rights watchdog, has become little more than a complaints desk.

Between November 8, 2024 and April 29, 2025, at least 250 new complaints were lodged, but none have been resolved.

Despite its 73-member staff continuing to receive complaints, the absence of its three decision-making benches has stopped all activities.

"We are only receiving complaints and carrying out administrative tasks," said NHRC Secretary Sebastin Rema. "There is no information on when the commission will be reconstituted."

Deputy Director Farhana Syead said, "People come every day asking about the status of their cases, but we cannot offer them any satisfactory answers."

In 2024, the commission received 751 complaints, but only 373 were resolved. Most involved minor disputes such as wage issues, labour conflicts, family matters, and land disputes.

Of the 100 suo motu (self-initiated) cases opened in 2024, only 20 have been concluded.

Even before the current leadership void, the NHRC was widely criticised as a "toothless body" offering recommendations without enforcement powers.

By law, the commission cannot investigate law enforcement or intervene in cases before courts or the ombudsman, excluding it from many of the country's most serious human rights cases.

Critics argue this design is intentional.

Under Sections 6 and 7 of the NHRC Act, the president appoints the chairperson and members based on recommendations from a selection committee largely made up of ruling party allies.

This structure, rights advocates say, violates the Paris Principles, which stress that reduced political interference strengthens institutional credibility.

Over the past three terms, the NHRC has been led by former government secretaries: Dr Kamal Uddin Ahmed (2022–2024), Nasima Begum NDC (2019–2022), and Kazi Reazul Hoque (2016–2019).

"Sadly, the last NHRC head was a former home secretary, someone we repeatedly contacted about law enforcement abuses and never heard back from," said Dr Mizanur Rahman, NHRC chairman from 2010 to 2016.

"How can we expect someone to act independently when their entire career has been about following government orders?"

"It's not enough to fill the chairs," said rights activist Nur Khan Liton. "We need a commission capable of holding state actors accountable, something this institution, by structure and statute, cannot do," he said. "We don't want bureaucrats leading the NHRC, we want rights defenders in leadership."

"It must be empowered to investigate law enforcement, intelligence units, and security forces -- those most frequently implicated in rights abuses," he said. "The NHRC must operate free from political control to protect citizens without fear or favour."

Sheikh Hafizur Rahman Karzon, law professor at Dhaka University, said, "A real commission could hold influential violators, often state-linked, accountable."

Experts also questioned the NHRC's dependence on foreign funding and its failure to utilise legal powers.

Although empowered by Article 102 of the Constitution to file petitions on behalf of victims, it rarely exercises this right, weakening its credibility. Only 25 percent of its budget comes from the state; 75 percent is from international development partners.

Bangladesh Mahila Parishad President Fauzia Moslem warns that this institutional paralysis comes at a "dangerous time".

As political violence rises, law enforcement abuses increase, and women and minorities grow more vulnerable, the need for a functioning NHRC is critical, she said.

"The commission could have been a refuge for abused women," she said. "Instead, its silence leaves them powerless."

To enable the selection committee to function amid vacancies, the government amended the NHRC Act on November 20 last year.

The ordinance allows any member to chair meetings in the absence of the chairperson and states that flaws in the committee's composition will not invalidate its proceedings.

Yet, no progress has been made in reconstituting the commission.

Contacted, Legislative and Parliamentary Affairs Division Secretary Hafiz Ahmed Chowdhury said he has not yet received any instructions on the matter, and the law adviser is the appropriate person to comment on it.

This correspondent called the law adviser several times on his mobile phone and also sent text messages for comments but got no response.

Several other NHRC officials said they are still in the dark about the commission's reconstitution.

Dr Mizanur Rahman identified three urgent reforms to secure full accreditation: reducing government control, allowing the commission to investigate law enforcement abuses, and ensuring financial independence from the law ministry.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments