Reverse migration rises twentyfold in five years

A few months after his honours examinations at a college in Satkhira in 2018, Quazi Monjurul travelled to Dhaka looking for a job.

After around four months, he was hired by a company.

As his initial salary was not much, he struggled to bear the living expenses in the city and send some money to his parents in Kaliganj, Satkhira.

"The pressure from both inadequate job opportunities and high cost of living forces people to migrate."

After he received a few raises, he got married at the end of 2019 and rented a two-room flat in Pallabi.

Then came the Covid-19 pandemic. His company closed for good and it was not until three months later that he got another job. But the salary was smaller than the previous one.

Monjurul is one of the millions of people whose lives were upended by the pandemic.

"It became very difficult to make rent and support my family even after I got the job. I used up all my savings. Sometimes I contemplated going back home," said Monjurul.

But he kept trying to find other jobs and struggled to make ends meet in the city. In 2022, his wife gave birth to a daughter. In the months that followed, the prices of food and the cost of living rose. But his earnings did not. Finally, in July last year he travelled back to his village.

"I tried my best, but running my family in Dhaka and supporting my elderly parents with an income of Tk 25,000 was impossible. I had no choice but to return," said Monjurul who now has a small poultry farm in his village.

"At least I don't have to pay the rent now."

Like him, many people return to their villages amid rising costs of living, a sense of insecurity and scarcity of jobs.

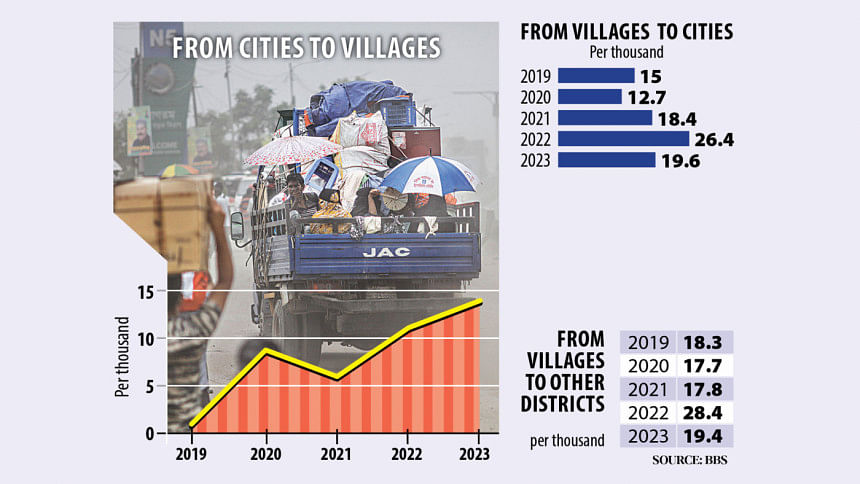

More and more people have been migrating from the city to the villages for several years, according to Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics published by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

The study surveyed more than 3.08 lakh households across the country and found that 13.8 out of every 1,000 people returned to the village in 2023. Such migration rose by almost 20 times since 2019.

The number of people who moved to urban areas from villages fell to 19.6 per thousand in 2023 from 26.4 in 2022, says the report.

Alamgir Hossen, director of the Sample Vital Registration System project, said the pandemic was one of the key causes of reverse migration. A section of people could not recover from the loss of earning and left the cities.

People choosing not to migrate to the cities means they are trying to make it in the villages.

"Many people, however, are still coming to the cities in search of jobs and some are succeeding in finding one," Hossen said.

Hossain Zillur Rahman, executive chairman of the Power and Participation Research Centre, said besides high food inflation, there were rising rents and transportation costs.

On the other hand, job opportunities and people's earnings in the major cities had declined.

"The pressure from both inadequate job opportunities and high cost of living force people to migrate," he told The Daily Star.

Former vice-chancellor of Jahangirnagar University Prof Abdul Bayes said, "People from the lower-middle income group are leaving because they believe the civic amenities have become better in rural areas. Besides, modern technology is also available there."

This group also believes that the cost of living in the cities is very high and so is the insecurity, he added.

Prof Bayes said infrastructure development outside the cities was a key driver of reverse migration.

"Due to smooth communication services, people's mobility has increased. People come to cities and leave after doing what they came here to do. The earning opportunities also increased to some extent in the village.

"The reverse migration will continue to rise in the coming days, and we should equip our villages with the necessary infrastructure," he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments