Sewage pollution killing city’s water bodies

Most parts of the capital remain outside the sewerage network of Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (Wasa), which has yet to implement a master plan adopted a decade ago, resulting in rampant pollution of rivers, canals and other water bodies in and around the city.

The plan recommended setting up five sewage treatment plants across the city, but only one -- the Dasherkandi plant -- was built on 62 acres of land in the capital's Khilgaon at a cost of Tk 3,482 crore two years ago. The plant can treat five lakh tonnes of sewage per day, but it is yet to be connected to Wasa's sewerage network.

Wasa officials could not provide any data on the volume of sewage being discharged into the city's water bodies. According to an estimate by experts, around 20 lakh tonnes of sewage are generated in the city every day.

According to experts' assessment of the existing sewage treatment capacity, more than 90 percent of the megacity is not covered by Wasa's sewerage network. In the absence of proper facilities, people are often left with no choice but to connect sewer lines to stormwater drains, lakes and canals, aggravating the city's water pollution.

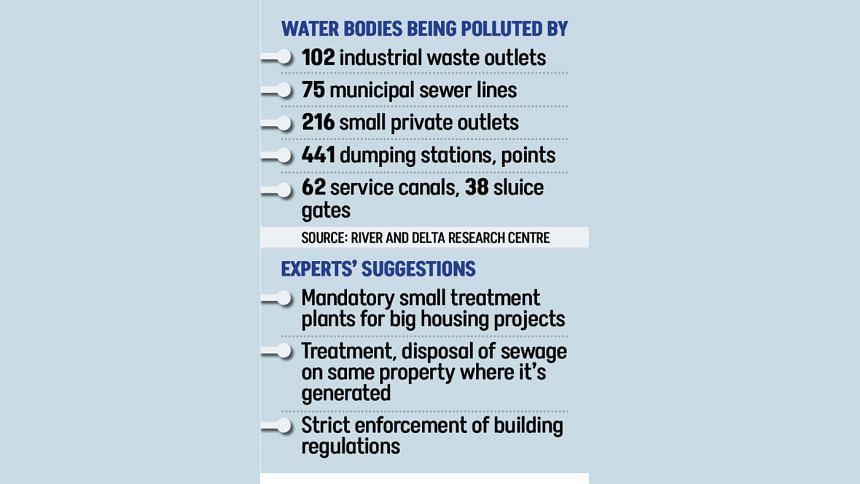

A recent study by the River and Delta Research Centre that carried out field surveys and used satellite imagery uncovered alarming levels of pollution in the Buriganga, Turag, Shitalakkhya and Balu rivers encircling the city.

It identified 102 industrial waste outlets, 75 municipal sewer lines, and 216 small private outlets that discharge untreated waste into water bodies.

Moreover, contaminants are being channelled to the rivers through 38 sluice gates and 62 service canals alongside 441 dumping stations and points. Industrial units, dockyards and kitchen markets further compound the pollution.

Adil Mohammad Khan, president of Bangladesh Institute of Planners, said it's difficult to implement large-scale projects in many city areas due to high population density and narrow roads.

"It took more than 10 years and crores of taka to build Dasherkandi plant, but the facility is operating outside the sewerage network."

Terming the Wasa master plan unrealistic, he said that drawing up a plan for a new area is easy, but it's difficult to devise one that can be applied to a built-up city.

Adil urged the authorities to draft a new master plan putting emphasis on localised solutions such as mandatory septic tanks, small-scale treatment plants, and strict enforcement of building regulations.

He said the current construction rules have a provision of installing septic tanks in buildings in areas outside the sewerage network. "To implement it, Wasa, city corporations and Rajuk will have to step up their efforts. All owners must comply with this provision while constructing buildings."

Small treatment plants must be set up in big housing project areas like the one at Uttara Sector-18, Adil noted.

Md Mujibur Rahman, a teacher of civil engineering at the United International University, emphasised the importance of "onsite system" that treats and disposes of sewage on the property where it is generated, typically in areas without access to public sewer infrastructure.

"More than 90 percent of Dhaka city lacks proper sewerage, and almost all human waste is dumped into water bodies, putting ecosystems in peril," he said.

The Dasherkandi plant is a good sewage treatment facility. But it runs without a network. The plant currently processes wastewater and sewage diverted from Hatirjheel before releasing treated waste into Begunbari canal, said Mujibur who led the project "Integrated Development of Hatirjheel including Begunbari Khal".

Pointing out that high-rises without septic tanks directly pollute drains and canals, he said, "Construction of small modular treatment plants should be made mandatory for high-rises. The technology is there, and the cost is comparable to that of the installation of a lift.

"If we can improve and modernise onsite systems alongside construction of treatment plants, sanitation will gradually improve," Mujibur said.

In the past, two Dhaka city corporations had made several attempts to block sewage outlets into lakes and canals and enforce the provision for installing septic tanks in buildings, but those efforts did not yield any results.

Recently, Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha (Rajuk) came up with a fresh initiative: every high-rise must have a small Sewage Treatment Plant (STP).

"We have written to the relevant department, making STPs mandatory for high-rises. Rajuk will not approve any plan unless this provision is adhered to," said Mohammad Harun-Or-Rashid, member (development control)of Rajuk.

He warned that failure to install an STP during construction would be considered as a violation of the regulations, leading to design cancellation and legal action under the building construction rules.

WASA KEEPS STRUGGLING

Wasa's master plan proposed setting up plants in Dasherkandi, Uttara, Mirpur and Rayerbazar, along with the rehabilitation of Pagla treatment plant. However, only one has been constructed in Dasherkandi, while the Pagla plant remains in disrepair, running at less than half of its capacity to treat 120,000 tonnes of sewage per day.

Citing a shortage of funds and land as major barriers to implementing the master plan, a top Wasa official said the Dasherkandi plant now processes mainly wastewater, handling between three and five lakh tonnes daily. If brought under Wasa's sewerage network, it could treat up to five lakh tonnes of sewage per day.

It will require Tk 3,000 crore to link the plant to the sewerage network and set up sewage lifting stations. In September last year, a project proposal was sent to the LGRD ministry, which is yet to approve it, said the official.

Besides, a feasibility study on a sewage treatment plant in Uttara is underway, mentioned the official, adding that Wasa is struggling to acquire land for its Mirpur and Rayerbazar treatment facilities.

Experts warn that relying solely on large-scale treatment plants could mean waiting decades for results. They advocate immediate action: enforcement of regulations on septic tank installation, setting up of small treatment units, and rehabilitation of existing sewage treatment facilities.

"Without swift action, Dhaka's water bodies will remain dumping grounds … We need practical and localised solutions to safeguard public health and the environment," said Mujibur.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments