Widespread graft was the norm, not exception

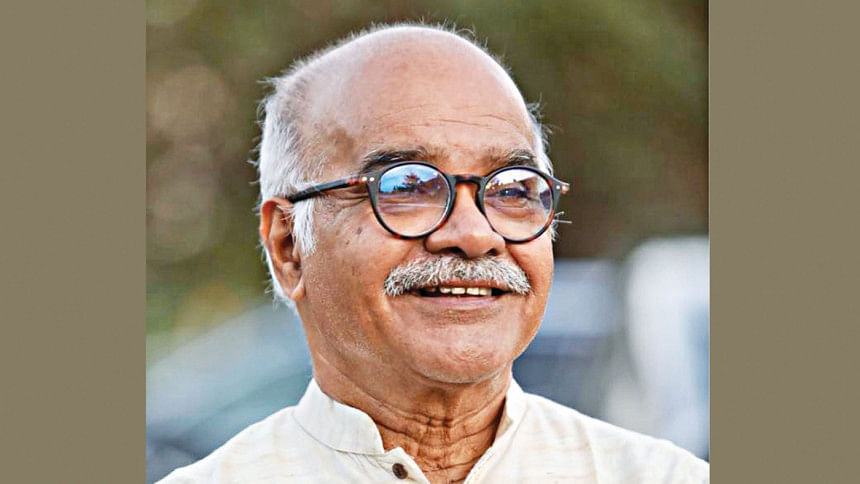

The Awami League regime's economic strategy was not always based on equity. Rather, its policies and measures often had serious biases towards the urban and affluent people, leading to widening inequalities, economist Selim Jahan has said.

The rich enjoyed better services while substandard services were meant for the poor and marginalised groups, the former director at UNDP's Human Development Report Office and Poverty Division said in an interview with The Daily Star.

Jahan, a former Dhaka University professor, also discussed challenges for the interim government and proposed a five-point strategy to overcome these obstacles.

He said the AL government's policies had three basic characteristics. Firstly, economic discipline, rules and regulations were frequently violated.

"Megaprojects were undertaken right and left without any objective cost-benefit analysis," said Jahan.

Secondly, he said, the framework of transparency and accountability was thrown away. "In the absence of transparency and accountability, wide-spread corruption at all levels of economic structure became the norm, not the exception."

"It not only represented resource leakage but also destroyed the value system of the society."

Thirdly, proper and objective monitoring and evaluations of programmes and projects were not undertaken as needed most of the time.

So, economic decisions were ad hoc to a large extent often did not reflect the aspirations of the people. These were mainly bureaucracy-driven, non-participatory, and top-down on many occasions, not bottom-up.

Furthermore, strategies were not based on data, evaluations and facts, but sometimes on the basis of perceptions, said Jahan, who had also worked as an economic adviser at the Planning Commission.

AL BYPASSED INCLUSIVITY

The previous government's economic policies historically favoured affluent groups, providing avenues for wealth accumulation through loan defaults, tax evasion, and corruption.

This "troika" of state machinery, business interests, and wealthy elites exploited public resources without accountability, widening the gap between rich and poor, Jahan said.

About the previous government's approach to democracy, Jahan argued against putting democracy and development as mutually exclusive matters.

Democracy has intrinsic value, independent of its impact on development while the government sought to justify authoritarian practices by emphasising rapid economic growth, Jahan said.

"Democracy fosters equitable, sustainable development by ensuring transparency and accountability," he remarked.

"Bangladesh must pursue democracy and development

simultaneously. The notion that democracy could be compromised for the sake of development is against the interests of the people," said Jahan.

Genuine development should reflect a participatory, democratic structure to ensure that it remains inclusive and sustainable, he added.

Bangladesh's impressive GDP growth has not translated into sufficient job creation, especially for educated youth, as Jahan explained that while the economy grew at 6 percent, the quality of this growth has been compromised.

"The focus on capital-intensive industries sidelined employment-generating sectors, resulting in jobless, voiceless, and rootless growth."

The previous government prioritised high growth rates, bypassing the need for inclusive and environmentally sustainable growth. As a result, economic gains have not been widely shared, and the growth process has often ignored the socio-cultural fabric and environmental concerns of Bangladesh.

He contrasts "progress" with "development," arguing that while Bangladesh achieved quantitative economic progress, it neglected qualitative development.

PERSISTING INEQUALITIES

While discussing Bangladesh's socio-economic strides, its challenges, and the pivotal steps required for sustainable development, Jahan said Bangladesh's journey from a war-torn country in 1971 to a burgeoning economy in 2023 was remarkable.

With annual GDP growth averaging nearly 6 percent between 1991 and 2023, Bangladesh's economy expanded thirteenfold, from $35 billion to approximately $447 billion.

The poverty rate fell drastically, from 58 percent in 1990 to 19 percent in 2023. This growth fuelled advances in health, education, and infrastructure, pushing life expectancy up from 58 years to 73 years and primary school enrolment to 97 percent.

Jahan noted that Bangladesh also outperformed its neighbours in key human development indicators. For instance, the under-five mortality rate per 1,000 live births stood at 31 in 2019, lower than India's 34 and Pakistan's 67.

Furthermore, Bangladesh's Human Development Index value jumped from 0.394 in 1990 to 0.661 in 2019. By 2015, Bangladesh attained lower middle income status, edging towards official graduation from the Least Developed Country bracket in 2026.

Despite these successes, significant deprivations linger, according to Jahan. Roughly 31 million people still lived in poverty as of 2023, and many struggled with inadequate access to essential services, such as safe drinking water and healthcare.

Economic disparities persist, with notable gaps in education, healthcare, and income, the economist said. For example, the under-five mortality rate for the poorest quintile was 49 per 1,000 live births in 2023, more than double that of the richest quintile.

Gender and regional inequalities also present challenges, with rural populations experiencing significantly higher rates of multidimensional poverty than urban residents, Jahan observed.

Bangladesh's income disparity has reached historic highs, with the top 10 percent of the population controlling 38 percent of national income, while the bottom 40 percent control only 17 percent.

Jahan identified three primary contributors to this inequality: unequal access to education and employment, affluent biases in policy, and the unchecked accumulation of wealth by powerful elites.

With three distinct education streams—public, elite private, and madrasa— from where students emerge with different skill levels and job opportunities, further entrenching inequality.

5-POINT STRATEGY

Following the political transition, the interim government faces substantial economic obstacles, including elevated inflation, decelerated industrial production, and a struggling banking sector, he said.

Although the government has tightened the monetary policy, stabilised the exchange rate, and improved remittance inflow, Jahan highlighted the importance of understanding the complex roots of these factors for effective solutions to the problems.

Tackling inflation, for example, requires more than monetary tightening; it demands addressing structural issues like syndicates controlling the supply of goods, he pointed out.

Jahan advocated for simultaneous political and economic reforms, recommending a phased, prioritised approach to reform spanning immediate, short-term, and long-term actions.

He noted that success depends on the government's capacity to withstand resistance from vested interest groups and to foster a cohesive vision for overcoming current challenges.

Looking ahead, Jahan proposed a five-point strategy for the interim government to address inequality and drive inclusive growth.

Firstly, he recommended an objective assessment of past policies to set future directions.

Secondly, a national dialogue should engage marginalised groups, fostering a collective vision for inclusive development.

Thirdly, a rolling three-year plan should prioritise growth in sectors employing the poor.

A strategy with emphasis on the collection of disaggregated data on specific areas and groups will be needed to steer the country forward, Jahan said.

And a comprehensive social protection strategy to assist people in need will be required, according to him.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments