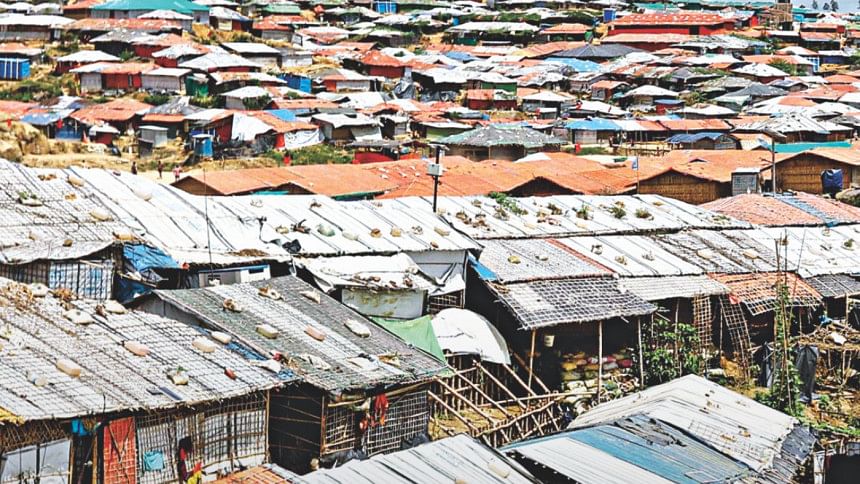

From an elephant jungle to the world's largest refugee camp

At the edge of a winding uphill road, right next to a host of tea stalls busy selling cigarettes from Myanmar and entertaining Rohingya teenagers, lies Sufia's home.

Made out of plastic sheets and bamboo poles, Sufia's residence, like the rest in Kutupalong camp, has just about enough room to accommodate her family of six. That morning, however, there were about a dozen children buzzing on the floor of her 'guest room', screaming out English alphabets at the top of their lungs.

Ask them what two plus two is, and they will jump right at you. "Four!" shouts Saidul, a five-year-old wearing a brown lungi and a blue sleeveless vest. Move into the higher double digits though, and you find a couple of heads being scratched and a few sheepish smiles.

Barely 17, Sufia has taken the responsibility to ensure that the fate of the next generation of Rohingya turns out to be better than hers. She transforms her home into a school every day where she teaches children Burmese, English, and Mathematics.

"I want these children to study like I did. That's why I teach them here. Back home (in Myanmar), girls can study till grade 10. I studied till grade 8," says Sufia. It has only been a month since she started her small school. But she has already realised that these children, most of whom are below five years of age, need plenty of help.

"When I teach them Burmese, some of them ask me when we can return home. And then they start talking about the atrocities and the killings of August 25. They get scared. That's why I try not to make them recall those days," explains Sufia, who was trained as a teacher in the camps before she started her school.

It's not just the children. Even Sufia's mother, Hamida, panics when she recalls how her relatives and villagers were killed right in front of her. She explains that her family left their hometown on August 25, the day the Rohingya exodus began.

"Our village was attacked with bombs. Some people died, some lost their legs, and others ran for their lives with whatever they managed to carry. It was total chaos. Our homes were destroyed! My head spins whenever I think about those days," shares a wide-eyed Hamida.

"After reaching Kutupalong, we lived on the streets for two weeks before a home was built for us. Those days were very difficult. We used to struggle to get food. But things have changed a lot since then. Today we get rice and dal on a regular basis. It's a bit hot here, but we are doing well," she adds.

From chaos to stability

One year ago, the camps at Ukhia seemed incapable of hosting such a huge influx of refugees. Like Hamida's family, most of the newly arrived lived on the streets outside the refugee camps for days. The locals at Ukhia were the first ones to help them. Soon after, the region started receiving aid from various parts of the country.

While there were hundreds of trucks coming in with food and supplies, there were very few distribution points and most of the Rohingya weren't even aware of them. As a result, children and men would run after relief trucks and literally fight for food being thrown from the moving vehicles. It was the stronger and the more experienced Rohingya who would get the majority share of the pie, as opposed to the newly arrived.

There were also problems with the kind of supplies being donated. Almost every nook and corner of the camps was filled with clothes, rejected by the Rohingya, since they didn't need them. And it took camp officials several days to clear out the mess caused by these rejected attires.

Accessing some of the areas was also a major problem. One would have to walk through knee-deep mud in order to visit some of the newer camps formed further down the road from the Kutupalong refugee camp, which made it difficult for aid workers to reach the refugees.

One year on, however, there seems to have been a dramatic shift in the way things are being run. For starters, the area has been divided into 32 camps and there are camp-in-charges (CIC) in place to ensure that everything runs in a smooth manner.

The muddy pathways have been replaced with roads made of bricks.

Many of the hilly areas, which are prone to accidents, have proper steps now. According to the Inter-Sector Coordination Group (ISCG), a coordinating body of international organisations, 40 kilometres of roads have been built in Ukhia and Teknaf; 10 bamboo footbridges and six footpaths have been installed so far.

Today, there are designated distribution centres where the refugees line up and get their stash of food and supplies. Employment opportunities have been emerging as well. A number of people in the camps work on constructing new homes, transferring pipes, and fixing roads, earning up to Tk 300-400 per day.

The camps, today, have spread across 6,000 acres in Ukhia, and it's expanding every day.

Shamimul Huq Pavel works for Bangladesh's Refugee, Relief and Repatriation Commission (RRRC). It's the government organisation that every agency is required to consult before making any move in the camps. Pavel is also a camp-in-charge (CIC) for five sites. He explains how the authorities managed to convert an elephant jungle into one of the world's largest refugee camps in less than a year.

"Both the international and the local bodies helped a lot. I think there are close to 10,000 people working here now. When I mean help, I don't only mean funding, but a lot of dedication. The people who came here were very dedicated to the cause," explains Pavel, "And then, there's our experience. Bangladesh deals with cyclones and other kind of disasters every year. We know how to distribute relief goods in such dire situations and our past experiences have helped us a lot in the case of the Rohingya crisis."

"Till now, there hasn't been a single death due to starvation and neither has there been an outbreak of a deadly disease. This is actually a miraculous achievement," he adds.

Mitigating gaps

The commissioner of the RRRC, Mohammad Abdul Kalam, says that the initial plans were 'mostly sporadic.' "From spontaneous interventions, we went on to planning for more specific issues. We sat down with our international partners and worked out on a plan," explains Kalam. "It's not as though everything was pre-planned, but we have managed to shape up something," he adds.

The approach was simple. The government and aid agencies assumed that they were building a new locality. Keeping that in mind, they listed down the kind of services that a new locality would require—such as food, health, education, sanitation, accommodation, communication, and so on. Each of these services were then applied to the camps.

While the simple approach was effective, it did have its gaps.

"From the toothbrush in the morning to the mosquito net at night, we tried to analyse and find out everything that they [the Rohingya] would need. But there were 1000 components and 1000 problems. We had to work on mitigating them," explains Pavel.

Some of the gaps that had to be mitigated were a result of a difference in culture and lifestyle. For instance, sanitary napkins were rejected by Rohingya women, so was milk powder. Many of them were found using milk powder to wash clothes.

Funding was and even still continues to be an issue. At the end of one year, UNICEF has only secured 34 percent of its USD 76 million goal. The WFP has received just 18 percent of the USD 243 million it requires to feed the one million Rohingya refugees.

Depleting forest cover

A coordinated effort over the last one year has helped deal with some of the most basic problems of the Rohingya, namely, food and shelter. However, there are more complex issues on the rise.

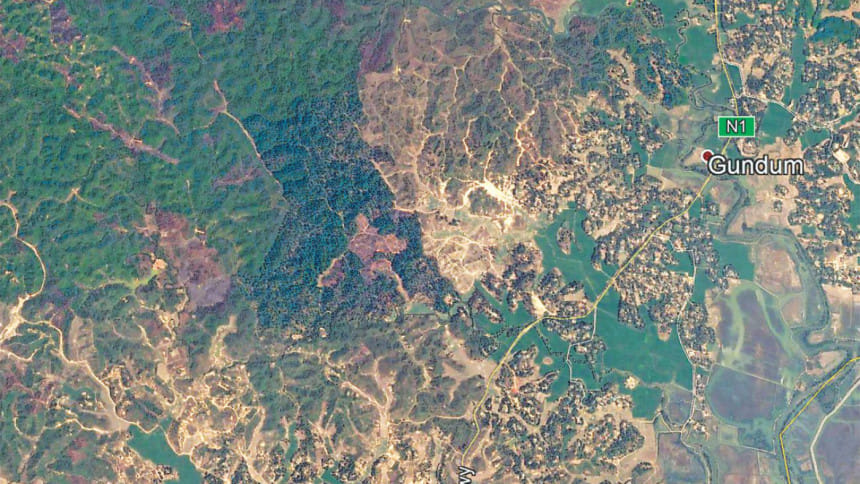

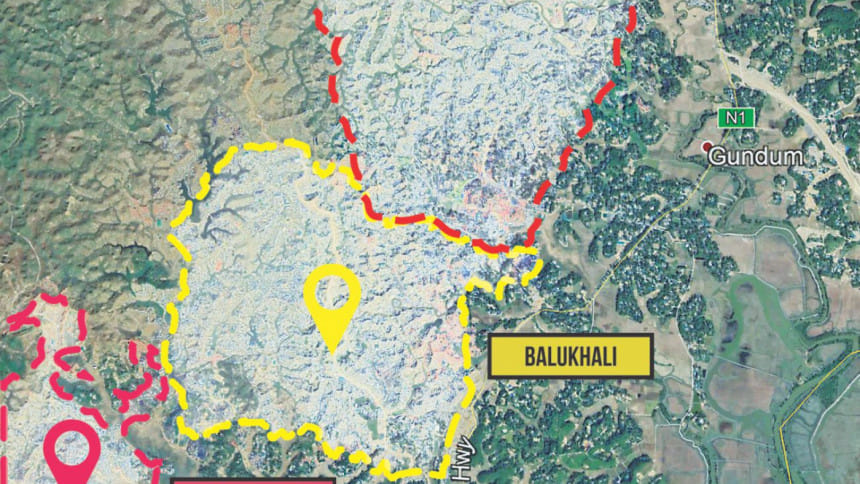

For instance, more than 2,000 hectares of forests, according to the ISCG, have been depleted in order to accommodate the newly arrived. That's essentially 700 tonnes of forest disappearing each day. Government officials say that at this rate all the forest in Ukhia might disappear by 2019.

Perhaps the best way to understand how much forest land the region has actually lost is by analysing satellite images on Google Earth. Comparing the pictures of the Rohingya camps in its current state to that of the camps a year ago provides an extremely dismal picture, describing the loss in forest cover.

The government claims that once the Rohingya population returns to Myanmar, they will begin projects to regain the forest cover. That's the reason no permanent structures are being built in the region.

However, with no clear idea on when, if ever, repatriation will begin, the government's plans of recreating the jungle in the area might have to wait for a very long time. In the meantime, different aid agencies are supplying the camps with gas cylinders in a bid to stop them from depending on the forest for firewood. While plenty of wood was initially used to build houses for the Rohingya, today, it's used mostly for cooking.

Gender-based violence

Cases related to sexual violence have also drastically increased over the year. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), hundreds of incidents of gender-based violence continue to be reported weekly.

"We get a lot of cases where women are badly beaten up by their husbands. As the men don't really have much to do in the camps, some take out their frustrations on the women over seemingly small matters," explains a counsellor with the One Stop Crisis Centre in the Kutupalong Camp.

"It's tricky when the cases are severe because we cannot simply refer all the cases to the thana, as most of the refugees will not be able to fight the cases in our courts, but we also need to ensure that the perpetrators do not get away with their crimes," the counsellor adds.

Maintaining a balance

Some of the other issues at the fore include family planning, the absence of a proper education system for adolescent Rohingya, the changing dynamics with regards to the host community and trafficking.

The wide array of problems is interconnected and the government has the difficult responsibility of cautiously manoeuvring through these issues and maintaining the camp's social equilibrium.

One of the goals will be to ensure that the people in the camps have activities to pursue. "There are one million people in the camp. They live in a very crowded environment. Issues like domestic abuse and sexual harassment can only increase if they have nothing to do. These are issues that need to be handled carefully," explains Kalam, head of RRRC.

Despite the improvements witnessed in the camps in the last one year, the government's main goal will always be to repatriate the Rohingya. People like Hamida, though, don't believe that it's going to happen any time soon.

"I won't go back till we get accepted as citizens. I saw people get killed with my own eyes one year ago and I don't want to suffer a similarly painful death."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments