The fight for Rohingya rights

Deep in the Kutupalong refugee camp is the headquarters of an organisation calling themselves the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights. From outside, it is indistinguishable from neighbouring shacks made of bamboo and plastic but more spacious, like a schoolroom in the camps. Inside, the fight for Rohingya rights is quietly happening.

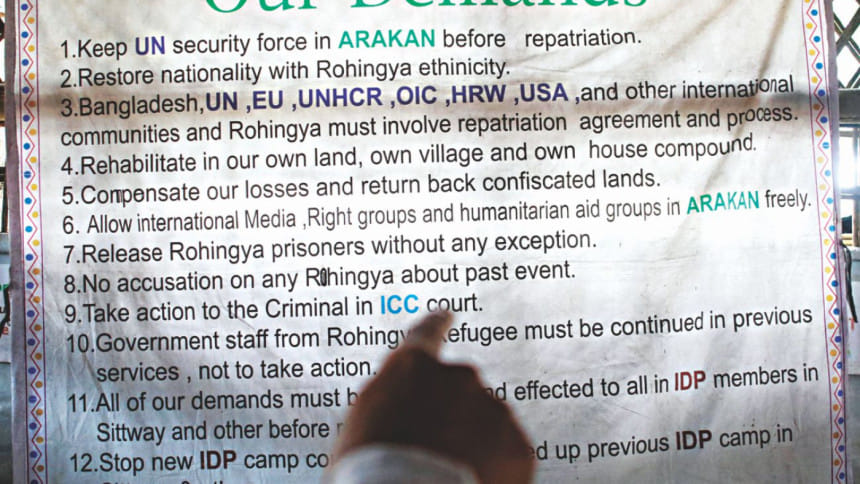

Men sit in plastic chairs lined up against the walls of the shack, talking quietly. The walls are covered in banners, including one titled "Our Demands". The first demand is for UN forces to be stationed in Rakhine State before repatriation of more than a million Rohingya refugees now in Bangladesh.

Other demands include the restoration of their nationality as citizens of Myanmar and recognition of their Rohingya ethnicity, and rehabilitation back onto the lands and villages from where they have been uprooted. Posters on the walls declare "Not Bangali" and "YES Rohingya".

The society moved to Bangladesh last year, in the months after the Myanmar military unleashed an operation that sent more than 700,000 Rohingya fleeing to Bangladesh. The society is also doing their bit to create a historical record of the atrocities they were subject to—creating lists of Rohingya Muslims killed in last year's military crackdown in Rakhine. The number they have come up with is over 10,000—significantly higher than a survey conducted in the camps by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) last year, which estimated that 6,700 Rohingya were killed.

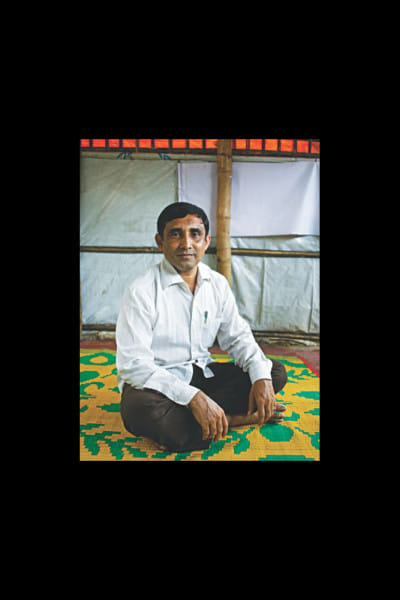

Yahya, a member of the society, says mostly educated Rohingya men gather here to discuss and work for the rights of their people. "We have come here [to Bangladesh], having had our rights taken away there. It's been a year now. Everyone has seen what was done to us. Why haven't we got our rights yet?"

The repatriation deal: A point of access, not a 'final agreement'?

In June, a memorandum of understanding (MoU) between UN agencies and the Myanmar government, a draft of which was leaked online, revealed that Rohingya refugees cannot expect much change back home on their proposed return. The UN is yet to publicly release the final MoU, which Rohingya community leaders have criticised heavily, saying that they had been left out of deliberations entirely.

The UN considered negotiations over this agreement as paramount to restoring access to the state of Rakhine for UN agencies, which have been barred from the region since the violence in August 2017. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, on his visit to the refugee camps in Cox's Bazar in July, stressed that the agreement was "to pave the way for potential future returns" with the government of Myanmar and "[n]ot as a final agreement on returns".

Noticeably, the tripartite MoU does not refer to the Rohingya by name, instead referring to "displaced persons from Rakhine State who have been duly verified as residents of Myanmar" as eligible for return. Citizenship is mentioned conditionally, although it is a key demand of the Rohingya refugees. UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, has called this MoU "the first and necessary step" to create conditions conducive for the return of the refugees.

Mohibullah, chairman of the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights, tells Star Weekend, "We will not accept these identification documents. These identify us as Rakhine Muslims and not as refugees and as Rohingya." Since 2015, the Rohingya have been required to carry National Verification Cards (NVC), a residency document provided by the government, which community leaders such as Mohibullah reject, as falling short of citizenship. The end of the NVC system is another key demand of the refugees.

The 1982 citizenship law stripped the Rohingya of citizenship in Myanmar. Many of their previous identification papers were taken away from them or rendered useless, making the group unable to vote in the 2015 elections or move about freely. The government of Myanmar does not refer to them as "Rohingya", calling them "Bengali" or "Muslim" instead. The Rohingya are largely considered interlopers from Bangladesh, even though many have lived in Rakhine for generations. The military crackdown in August last year was the tipping point.

Just as the agreement does not explicitly guarantee citizenship, it similarly does not guarantee freedom of movement. The MoU states "returnees will enjoy the same freedom of movement as all other Myanmar nationals in Rakhine State". So, freedom of movement beyond the borders of the region is not guaranteed nor is why the Rohingya were earlier not allowed to travel freely within Rakhine, addressed.

Despite the deal having been signed in June, the UN recently said that it still did not have access to Rakhine. In a statement, it said that substantial progress was needed in three key areas— "granting effective access in Rakhine State; ensuring freedom of movement for all communities; and addressing the root causes of the crisis".

These, in a nutshell, are the concerns highlighted by Rohingya refugees and community leaders all along. Recognition as refugees, guarantee of citizenship, freedom of movement, and assurance of their safety are crucial for their return, says Mohibullah.

For example, the repatriation deal states that it is for those "who wish to return voluntarily, safely and in dignity to their own households and original places of residence or to a safe and secure place nearest to it of their choice." There is thus no clear guarantee that the Rohingya will be able to return to their lands in their own villages, a key demand of theirs. There is also the fact that hundreds of villages have been burned or razed to the ground by security forces, as has been seen in satellite images released by Human Rights Watch and other organisations.

"We will not accept this MoU unless we are properly accorded our rights. So far, no one [in the camps] has expressed their willingness to return," said Mohibullah.

Mohammad Nesar, in the makeshift settlement at Leda in Teknaf, says he has already been back to Myanmar twice since first coming to Bangladesh 12 years ago. "Before this, we refugees were taken back twice… though the Burmese government said that we would not be oppressed further, they went back on their promise and we were again wronged."

A survey of 1,360 Rohingya refugees conducted in the camps last year by the Xchange Foundation, an international migration policy and research organisation, found that 78 percent of respondents would return to Myanmar only if security, welfare, and the political situation improved. Their conditions for return, the survey found, were citizenship, freedom of movement and religion, and justice for the atrocities they were subject to.

The signing of the MoU between Myanmar and UN agencies, similar to earlier agreements, showed that the Rohingya refugees had once again been left out of discussions on their own fate. Following earlier waves of displacement in 1978, 1991, and 2016, similar repatriation deals had been struck. In 1978 and 1992 too, the Rohingya had not been consulted even though UNHCR was involved in facilitating returns. Many unwilling refugees were sent back, often by coercion.

Protests on June 16 were held in the camps to demand that the Rohingya be included in the repatriation discussions this time. More recently, protests took place on the anniversary of the August 25 military crackdown in Rakhine. Among other demands, was the telling "Never Again" referring to the atrocities that led them to flee their homeland.

There are still Rohingya refugees trickling into Bangladesh in small groups. Between January and mid-August, 12,936 new arrivals in Bangladesh were recorded by UNHCR. "The conditions on the ground are still not conducive to a safe and voluntary repatriation," said spokesman for the UN Secretary-General Stephane Dujarric on August 17. With the Rohingya still leaving Myanmar for the camps in Bangladesh, repatriation seems premature.

"We don't enjoy full rights there, when there is justice, we will of course return," says Nesar.

Their identity as Rohingya

Towards end June, the Bangladeshi government began biometric registration of Rohingya refugees with the help of UNHCR, but family-wise this time. "This family-wise registration data will be used for repatriation," says additional refugee relief and repatriation commissioner Mohammad Shamsuddoza.

Last year, the Ministry of Home Affairs had conducted individual biometric registration of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, which came to over 1.1 million. The director general of the Department of Immigration and Passports had said to the media that the database would identify Rohingya attempting to obtain national identification cards (NID) or Bangladeshi passports.

All refugees over the age of 12 are now having their fingerprints, iris scans, and photographs taken at UNHCR offices. They will then be issued new identity cards. According to UNHCR, this new verification will help consolidation of a unified and accurate database on the refugees.

However, at a recent meeting of the joint working group on repatriation of the Rohingya refugees in Naypyidaw, it was reported that Myanmar requested Bangladesh to use "Displaced persons from Rakhine State" instead of "Forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals" on the issued cards.

Bangladesh subsequently agreed. At the meeting, Myanmar also confirmed that they would be issuing NVCs to returning Rohingya. Both these decisions go against the demands of the refugees—that they be recognised as refugees and that the NVC is not an alternative to citizenship. When Bangladesh voiced the latter concern of the refugees, Myanmar only agreed to send teams to the camps to explain the benefits of the NVC.

"We do not want these new cards which will have 'displaced' on them and not mention that we are Rohingya," says Mohibullah. He stresses that they return as citizens with full rights as Rohingya and not as displaced persons, which may very well lead them to be interned in IDP camps.

"While changing a few words on a refugee's ID card may seem inconsequential, for the 700,000 Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh who fled ethnic cleansing in Myanmar a year ago, it is essential," said Bill Frelick, director of Human Rights Watch's refugee programme, in a statement. "This change signals that Myanmar doesn't intend to honour the citizenship rights of the Rohingya, nor acknowledge the causes of their displacement," his statement continues.

The return home

Currently, the physical repatriation process is yet to begin. Despite contrary claims by the Myanmar government, the Bangladesh government and UN agencies have stated that not a single Rohingya refugee has returned of their own accord, under the formal framework, a year into the influx.

In February, Bangladesh had given a list of 8,032 Rohingya refugees ready and willing to return. Myanmar subsequently only cleared 374 of them as eligible for repatriation, in March. According to Myanmar officials, some documents were incomplete. Such delays have consistently stalled the repatriation process.

The joint working group, comprising both Bangladesh and Myanmar government officials, visited Rakhine State last month to assess preparations for repatriation on the Myanmar side. "We went to where they took us and saw what they showed us. We weren't able to go wherever we wished," says Mohammad Abul Kalam, refugee relief and repatriation commissioner, of the visit.

The group was shown the two reception centres and a transit camp set up by the authorities in Rakhine. "They also took us to a few spots where some construction work is ongoing but so far as we know, those are camps for IDP [internally displaced persons] and unsuitable for those to be repatriated."

Existing camps in central Rakhine for those internally displaced in earlier violence in 2012 have been called 'concentration camps' and are notorious for already detaining some 120,000 Muslims, mainly Rohingya, who are unable to move freely and have no access to education, employment or healthcare.

Photographs of the transit camp in Maungdaw to accommodate returnees show desolate houses surrounded by barbed wire, more reminiscent of detention centres than of 'reception centres'. Such camps are exactly what Rohingya refugees are worried that they will be interned in permanently if they go back.

The holdback, says Kalam, is reconstruction of homes and villages for the Rohingya in Rakhine, which has not happened yet. The Myanmar authorities claim to have allotted 42 sites to resettle the returnees. Refugee demands and the terms of the agreement signed by the UN and Myanmar both call for rehabilitation in their original places of residence.

On the Bangladesh side, a repatriation centre has been constructed on the banks of the Naf river in Teknaf. Kerontoli was also where the 1992 returns took place.

While the conditions of safe and voluntary return this time are still being contested, one thing the refugees are united in is that they will return. "We have gotten a lot of benefits here from the Bangladeshi government, but all we want is to return to our country with our rights," says Yahya.

Includes parts of a story, "Return to more of the same for the Rohingya", published on July 13, 2018, in Star Weekend.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments