The “theatre” of rape

"[...] Think of the birangona not as the haunted spectre that would feed the imaginary of the nation but as one who has to make her life in the world in a mode of ordinary realism." Veena Das, in her foreword to Nayanika Mookherjee's The Spectral Wound

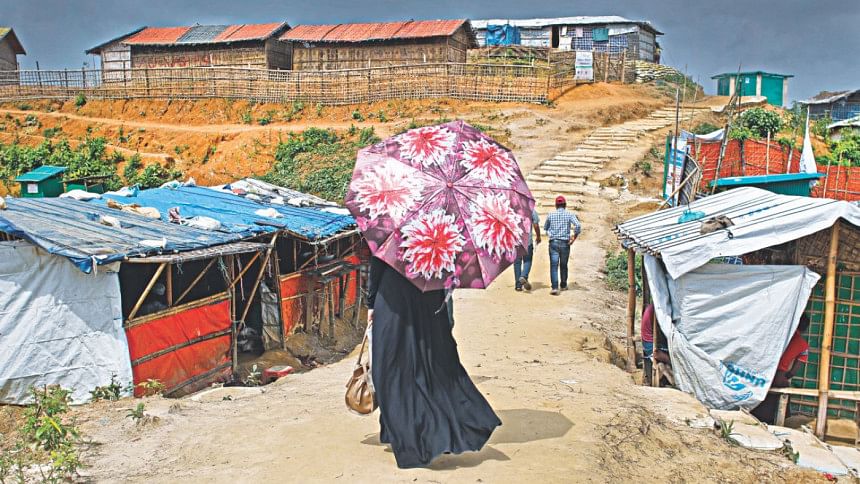

It is not possible, in good faith, to narrate the stories of the Rohingya women who were raped, without acknowledging the problematic politics of representation. When reporting stories of rape, it becomes imperative to ask the question: to what end? Unfortunately, there seems to be no clear answer to that anymore.

A year ago, the answer to that would have been that this kind of storytelling is important to document the experiences of women fleeing the Myanmar military. Women of all ages were raped and gang-raped by the military, and as they narrated what happened to them, it was an act of dissent. Here on free land, their stories sought justice, and perhaps for the first time in their life, the survivors had come in contact with people who listened to them.

A year on, the answer is a lot more blurred.

The women's stories have by now been used as evidence that, yes, rape was systematically carried out during the Rohingya genocide. It has taken several years of Rohingya women narrating stories of rape for the United Nations Secretary General to finally include the Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw) in its list of organisations that use sexual violence as a weapon of war. The list is made annually. As another August 25 passes by, the yearly update is that many of these women have now given birth to babies as a result of their rape. Their testimonies are important as we chart the post-conflict lives of these women.

Except the process of documentation is riddled with a power dynamic between the interviewer, community, aid-giver, and survivor, where the survivor is at the bottom of the rung.

The story of Samira's mother

Take Samira's mother for example. Baby Samira was brought to this world by the violent act of rape perpetrated by the Myanmar armed forces. We were led to the baby's mother by her husband last month. Except, when we got to her home, the mother was visibly distraught and refused to come out of the inner room, appearing only fleetingly to hand over baby Samira to her husband.

"She is just a little annoyed because a few foreign journalists came to meet her before you did," her husband Selim* said, trying to diffuse the situation. It became clear that the husband wanted the wife to talk to journalists but the wife had no such wish. We quickly told Selim that Samira's mother does not need to come out front if she does not want to. "She says that she feels like she is selling her body," he said.

That feeling must have been amplified ten-fold by the fact that as Selim entertained journalists in his tiny front room, a crowd of curious onlookers had gathered outside the door. Even when they were dispersed, they stood at a distance, listening in. The huts are so congested that it is difficult to do anything without alerting everyone.

Samira was born in the secrecy of her home, delivered by the woman next door. "That old mother," said Selim pointing to a woman in the distance, "she is the one that delivered the baby."

That Selim is his wife's spokesperson is further complicated by the fact that he married her while she was already pregnant with her war baby. In traditional Rohingya society, men hold a higher place in the hierarchy of the household—and Samira's mother being a pregnant rape survivor further compromises her position of power in relation to Selim.

"I married her because I felt sorry for her," he said, when asked why he did something most men around him would not. His wife is 22 years old, while he is middle-aged.

When we asked Selim why he wanted the story to be told, he replied, "So that babies like Samira get the help they need. But the help does not seem to arrive, so my wife is tired of talking." When asked to describe what sort of help he wanted, he did not have a clear answer but chose to reply with an example: "The baby gets sick very often and the hospitals are not treating her properly. The people at the hospital do not listen to what we are saying."

A few days later, Selim had a more definitive answer. Speaking over the phone, he said, "Samira has pneumonia. The Eid holidays are going on. We cannot treat her, because the hospitals are all closed. I need money to treat her at a hospital outside the camps." Even his wife, who had previously refused to talk, took the phone to reiterate the same thing, "Samira gets sick every three days. I don't know what to do. The camp hospitals are not being able to diagnose what's wrong. I don't have the money to do more." The urgency in her voice was unmistakable.

Her future at the camp is full of uncertainty and they want benefactors who will oversee that she gets a good shot at life—especially since the child's biological father will never come forward to take responsibility. On the other hand, his wife knows that if word spreads that Samira is a war baby, it will only make their lives more difficult—yet the kind of help that her husband is wanting will not be given to them unless they make the knowledge of her rape public.

This is the delicate balance that the war baby's parents are having to tread.

The story of Mahmudul's mother

Five-month-old war baby Mahmudul Hasan's mother was willing to talk. Yet even when the women are willing, a hierarchical system of access into the camps complicates the exchange. Each camp block has a team of community leaders known as "majhi". They are all men, and usually the first to greet any outsiders into the camp. This collective of majhis have teams of community sub-leaders working under them. They coordinate across camp blocks, and even camps, and are human databases of the residents of their blocks.

Mahmudul's mother too, could only be reached through one such community leader, Shamim. Shamim met us outside her home and led us directly into it.

The mother is a widow who cannot go out to work because of stigma and the general patriarchal rules that forbid Rohingya women from getting out of the house. "How can I go out to work?" she had told us. She is dependent on the charity of her neighbours for essentials outside of relief items. For example, on the day we met her, she prepared dried fish for lunch, which she got from a relative who lives next-door. Shamim, who brought us to her, also helps her out with "salun" (curry) to eat with the rice she gets from aid. The mother has four daughters in addition to Mahmudul to feed.

At the time of the interview, she pulled at her baby's tattered grimy vest and said that she needed new clothes for the baby. She said it not once but over and over again. Without any prompting, she went on to lament how worried she is that her baby is not getting breast-milk because she does not have enough to eat. "I have to go to the clinics and get powdered milk. I have trouble producing milk for him because I am not eating nutritious food," she said. "In Myanmar I had chickens and ducks and my husband's brothers caught fish for me. Food was not a problem."

The 30-year-old's has already been interviewed by many international news organisations including Al Jazeera, Los Angeles Times, and South China Morning Post. What is interesting is that in these interviews, her lived realities—the very real concerns of her day-to-day life are not depicted at all. Instead, the mother is homogenously identified solely through the details of her rape. They construct her vulnerability using the distant experience of being gang-raped in a field by two soldiers, and then giving birth to a war-baby. Her immediate vulnerabilities and coping mechanisms are not taken into consideration.

In an interview published in June, she told the reporters that she is yet to name the child. The child was three months old at that point. The narrator of the story added that "when she sees the boy lying in her arms, she relives a nightmare". He further added that "to name him, she thought, would be to accept what happened to her." A month later, a photo of her and Mahmudul were published in an article titled "Petrified and Stigmatised", but the story had no quotes from her. In another interview published last month, she gave a detailed description of how she was raped. Mahmudul's mother also told the interviewer that she cannot bear the thought of going to counselling centres because it means the truth will come out.

Most of these articles are homogenous depictions that fail to recognise that as much as she is stigmatised by what happened to her, the courage with which she is mothering the war-baby, is unsurmountable. For example, to ensure her survival, she speaks to numerous foreign media (not discounting the non-Rohingya, non-Burmese Star Weekend) while carefully maintaining her secret from her peers.

"I am happy to finally have a son after five daughters. This daughter of mine told me to put him for adoption but I didn't," she said, pointing at a young girl sitting by the doorway to her house. This counters the general media narrative that terms war-babies as "unwanted"—being unwanted at the time of conception does not mean they will be unwanted at all times—there will be time periods, when they are loved by their families.

Many researchers have documented that when perpetrators use rape as a weapon of war, it is an act of ethnic cleansing. It was no different for the Myanmar Armed Forces. Inseminating the "other" women with their own genes, while killing off the Rohingya male population, is a symbolic act of propagating the Burmese existence.

Well, Mahmudul's mother is about to foil that grand plan, even if it is only on an individual scale. "I will raise him to be a proper Muslim boy and a proud Rohingya," she said. She also told us that when Mahmudul was born, she whispered the azaan into his ears. "He will go to school and learn the Quran. I will circumcise him. I will never tell him who his father is. If anyone asks, I will tell them that his father was killed when escaping to Bangladesh."

Comments