Teen protest movement demanding safe roads: Their allies, adversaries, and others

The last time I heard of a student protest movement with secondary school children was in 2011. Secondary school children had joined university students in Chile to denounce their neoliberal education system that had commodified education, expanding social and income inequality between the rich and the poor.

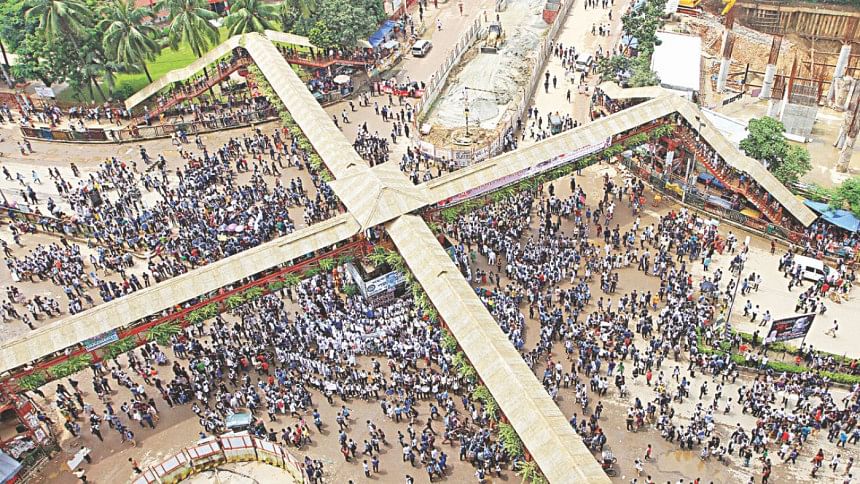

Seven years later, in Bangladesh, thousands of secondary school students were on the streets of Dhaka demanding road safety after two buses killed two students. Immediately following the accident, students blocked Airport Road, where the killings had taken place, demanding justice for the deaths of their two peers. That was July 29.

The protests continued, sparked by crude remarks by Shipping Minister Shajahan Khan. Soon after, students had made nine demands that included: capital punishment for reckless driving that result in death, an apology from the Minister, construction of foot-over-bridge where the accident had taken place, and greater student access to buses. In a separate statement, they had also demanded a resignation from the shipping minister.

At the outset, let me say that some of the student demands—such as the demand for capital punishment—should be taken with a grain of salt. That demand indicates their level of frustration with the system; their anger, their disappointment. Moreover, this demand needs to be seen in light of movements that they've witnessed before. When students demand capital punishment, they do it because that is the norm—that's merely the language of social movements that they've been exposed to and have consequently adopted. That does not mean that the State should institutionalise that into law in the name of "meeting student demands." Accidents happen, they need not be met with capital punishment if accidents cause deaths—but there has to be repercussions—and that is the point to take home. The larger goal of the movement is what is most important, and that goal is: road safety.

So, this is where allies of the student movement could have helped. The role of allies should have been to assist in refining student demands in light of the larger structural problems at hand. What the student protests highlight is that there is a clear need to revamp and reform the transportation sector. Possible solutions include introducing provision of public buses so that public transportation is not primarily provided by the private sector; new traffic laws (and lights) that actually control traffic—for example by restricting the number of cars per household; corruption free and straightforward processes to attain driving licenses, fitness tests and other paperwork; de-incentivising number of trips of buses; and incentivising safety. All these are structural solutions to a structural problem: unsafe roads. Holding individual bus drivers accountable, while useful from the standpoint of inculcating a culture of personal responsibility, will not lead to road safety without structural reforms in the transportation sector. The government should have invited student representatives to have these conversations with a view to initiate structural change.

But where is the time for dialogue when batons can be used instead of words as suggested by the violent eruptions across the city by law enforcement personnel and what appear to be government backed goons. Bystanders report policemen beating young boys and girls with batons and men in helmets attacking them with machetes. Perhaps they need to be reminded: this country has laws against violation of children's rights including their bodily harm. All those who are perpetrating violence against children should be held accountable under the Children's Act of 2013 that ratifies the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

In the case of the current student protests, the role of baton and machete wielding adversaries—even though safe roads are arguably a just cause that will benefit everyone—is, clearly, to make the current student protests seem like an anti-government movement. Why they would do so is unclear—maybe it is to disrupt solidarity and thwart the student movement in an election year because new leaders may be a potential threat to the current establishment. But that makes little sense.

Student demands for structural change for road safety are well aligned with the government's development agenda. In fact, this is as patriotic as a movement can be. The country's leadership should be proud of creating a generation of students who want to build a better country for themselves. Indeed, the ruling party is well placed to take on the challenges posed by students and appease the youth, the voter base that they've been nurturing through Young Bangla for instance, by working together with them.

***

The government has spoken. It has indicated that third parties have entered the game and that it may no longer protect the students on the streets. The Prime Minister repeated what other spokesmen of the government have been saying: that the student demands have been met and that they should go home. She called on parents, teachers, and professors to take the students back to their homes and classrooms.

The demand for "safe roads" is not so easy to meet, however. Unsafe roads are created by an amalgamation of factors: intense traffic because there are just too many cars on the road; bus drivers are incentivised to make as many trips as possible per day; high number of different types of vehicles with different speeds on the same roads; a corrupt transportation sector that makes things like getting driving licenses extremely difficult; blatant irregularities in implementation of existing traffic laws—to name a few. Unless there are changes in such arenas, roads will not be safe, not any time soon.

Meanwhile, the stakes have risen higher since the death of the two students on July 29. The one thing the State should have avoided is the use of violence against protesting students. Once violence was introduced, it was bound to get worse. When a man in uniform attacks a civilian, after all, everything changes. And it has.

The government has indicated that the helmet wearing, machete wielding men were not government backed goons but outsiders.

But what needs to be understood is that: it does not matter.

The political affiliation of those helmet crusaders is not important. If third parties can so easily perpetrate violence in the presence of law enforcement personnel, it speaks to a kind of dysfunction that has far reaching implications for the country in terms of who actually wields power. The ongoing attacks on the students point to a failure on the government's part to uphold citizen's right to protest, their right to be free from violence.

Meanwhile, the violence has dwarfed the importance of the broad demand of the student movement—road safety—as students now navigate unsafe, violent streets to uphold their democratic right to protest. That citizens are being picked up by law enforcement agencies for speaking out, such as photographer Shahidul Alam, is a further cause for concern. It seems what they call "spreading rumours" is far worse a crime than perpetrating violence because the men who attacked students with machetes—and are continuing to attack students—have not been arrested, even though news reports indicate that at least some of them have been identified.

***

When secondary school students had become the enforcers of law last week, there were bound to be some laughs as they meted out punishments like "write 'I will not drive without a license' 10 times." It was funny when a policeman was made to file a case against himself for not having a license and as such, breaking the law.

That was perhaps comic relief; it was needed right after the two deaths that instigated this student movement. But there is no comedy left, and definitely no relief.

We are now left with a situation that is so dire that even comic relief is hard to come by. But it must be said that the kind of solidarity building that we have seen over the past few days is phenomenal. That students joined in the protests as the situation got worse speaks to how fearless they are, and perhaps even how angry they are.

And with good reason.

What remains interesting, academically at least, is that the current movement debunks early theories from the 1960s about which students are likely to become activists—those with economic and social advantage. The current protest movement in Bangladesh shows that everyone has a tipping point, not just elite students with seemingly more time on their hands.

So, if we are to remember one thing about this student movement, it should be this: the location of this student movement is not an elite campus, but the streets of Dhaka. The initiators of the movement are not children from elite families, but children from different backgrounds.

And therein lies hope, because this is progress—it may not be linear, but it is still progress.

Nadine Shaanta Murshid is Assistant Professor, School of Social Work, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments