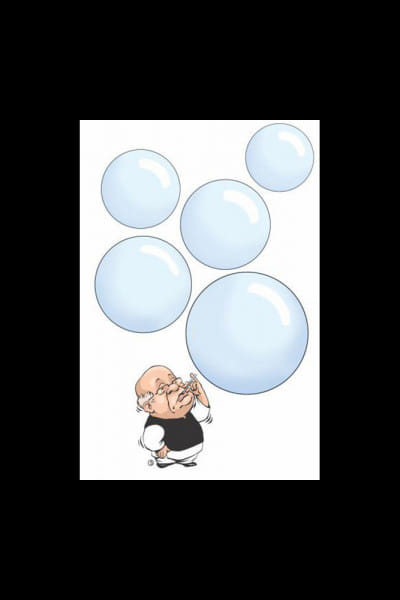

REPORT CARD ON MR. MUHITH

Like the bureaucrat he once was, Mr. Muhith has many process achievements to show -- power-point presentation of budget, greater use of ICT and online access to financial data, even a new colour for the budget document. Pre-budget consultations have been aplenty, never mind that these rarely leave a mark on the actual budget. It has not all been cosmetic either. Revenue, most times short of target, has nevertheless crept upwards under Mr. Muhith's watch even if overall tax-GDP ratio remains abysmally low. Deficit-GDP ratio has been kept within the IMF prescribed limit of 5 percent. Critical short-term fixes such as quick rental have averted a power breakdown though at very high governance and fiscal costs. There have been important policy milestones too – national social security strategy to name the most significant one. These are no mean achievements. But do they add up to what it takes to address the two most important economic challenges facing the country in 2015: propel the economy beyond the glass ceiling of 6 percent growth and overcome the burgeoning problem of multi-faceted inequality? The cold truth is that Mr. Muhith's and by extension the AL regime's overall economic record is very much one of a sum being much lesser than its parts.

Despite the often soaring rhetoric of the budget, actual allocation and strategic priorities have been strangely pedantic and lacklustre. This disconnect is most glaring on the challenge of growth acceleration, a challenge recognised by most including Mr. Muhith as central to the next phase of Bangladesh's economic journey. For the last decade or so that spanned Mr. Muhith's tenure and the 6th five-year plan, growth target above 6 percent rate has remained out of reach. What was earlier celebrated as resilience has metamorphosed into growth stagnation. But the three elements which can unshackle this growth stagnation the most – an energy policy and financing strategy, a skills strategy that delivers and a compelling sectoral strategy – are strikingly out of focus in Mr. Muhith's action plan.

Take the case of energy. 2015 budget allocations have prioritised power sector over energy continuing the policy short-termism that began with quick rental as a quick fix to the power crisis. The country is nowhere nearer to a policy decision on how best to use its coal resources. Success in settling the maritime boundary dispute is already a year in passing but little has moved in tapping the energy resources of the Bay of Bengal. Recent flurry of mega-deal signings has failed to convince investors as evident in the static private investment rate of around 21 percent. Mr. Muhith and the regime he represents appear unable to rise beyond policy short-termism in this most critical of growth enablers.

On the other strategic issue of human development, Mr. Muhith's lofty rhetoric appears to be only just that. While the critical challenge on the skills agenda is to match supply to market demand, the 2015 budget document only offers yet more top-heavy bureaucratic bodies. Astonishingly, allocations for the two human development sectors – education and health – have not just been static but in the case of health has actually declined in percentage terms. This, in 2015, when the transition from MDGs to SDGs calls for significant scaling up of engagement on health and education agendas.

The issue of education demands a deeper introspection for Bangladesh's economic future. Resource inadequacy is not the only concern here. The Education Minister appears unwilling to accept that there is a huge quality gap throughout the education system, most consequentially at the secondary education level. While there is no lack of projects, the entire educational outcome has become a victim of an official mindset that is devoting all energy on securing higher pass rates through an apparent policy of easy marking while showing less concern with actual learning outcomes. The discomforting consequence of this is evident when we find that a substantial chunk of skilled jobs in our industries and other economic enterprises are occupied by professionals from neighbouring countries with India alone claiming nearly $4 billion in remittances that flows out of Bangladesh. Mr. Muhith missed an opportunity of signalling a different intent if he had taken a bold initiative, for example, of allocating budget for a thousand or even a hundred new government secondary schools.

Bangladesh cannot break through the 6 percent growth ceiling without a bolder sectoral strategy. Bangladesh's economy has advanced thus far by banking on export-oriented industries and service-oriented domestic sector. Policy attention has been lop-sided towards the former mainly RMG while the latter has mostly grown despite policy neglect. Agriculture has been milked for its food security contribution but has received little support for its growth-driving potentials, for example through the growth-enabling sub-sectors such as aquaculture, dairy, livestock and forestry. While such a sectoral strategy has certainly produced dividends, it falls significantly short on the question of growth acceleration. This is where it is distressing to see that Mr. Muhith, despite some lofty rhetoric, has settled for narrow incrementalism rather than a bolder sectoral strategy.

One new element has been the talk about SEZs – special economic zones. The 2015 budget has touted SEZs as a key vehicle to jumpstart the growth process but like the equally touted PPP financing model of 2009 budget that largely failed to take-off, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating. There is also a danger that the policy dichotomy whereby foreign investors get pampered treatment via SEZs while domestic investors suffer policy neglect becomes more entrenched. In neighbouring India, SEZs have become a political hot potato because of its implications for land acquisition and land rights of farmers and rural dwellers. Such a debate is yet to start in Bangladesh.

Mr. Muhith has also been wanting on a bolder use of fiscal policy to advance equity goals. Sadiq Ahmad of PRI (Financial Express, June 22, 2015) has ably demonstrated this persistent failure. Data is showing that, in Bangladesh, it is not only the bottom 40 percent who have suffered a decline in their share of national income (from 18.22 percent in 1980 to 13 percent in 2010) but also the middle classes whose share declined over the same period from 51.53 percent to 46.5 percent. Over the same period, the 10 percent of the population classified as upper classes increased their share of national income from 30.25 percent to 40.5 percent (Bonik Barta, June 29, 2015). A significant part of the gains of the upper classes has come not through honest enterprise but through endemic corruption and political cronyism. Mr. Muhith has often been disarming with his candour on these dynamics as, for example, his recent admission that he cannot deal with banking mis-governance due to vested interests of his own party. The truth is, on the question of economic governance, Mr. Muhith is only a part player. Political and economic governance has always been intertwined in Bangladesh but under this regime, the blurring of these boundaries has occurred to such an extent that more than any policy deficiencies, politicisation of economic governance poses perhaps the biggest barrier to realising the twin goals of growth acceleration and equitable distribution of gains from growth.

The writer is executive chairman of Power and Participation Research Centre and former adviser to the caretaker government.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments