Not a practical option

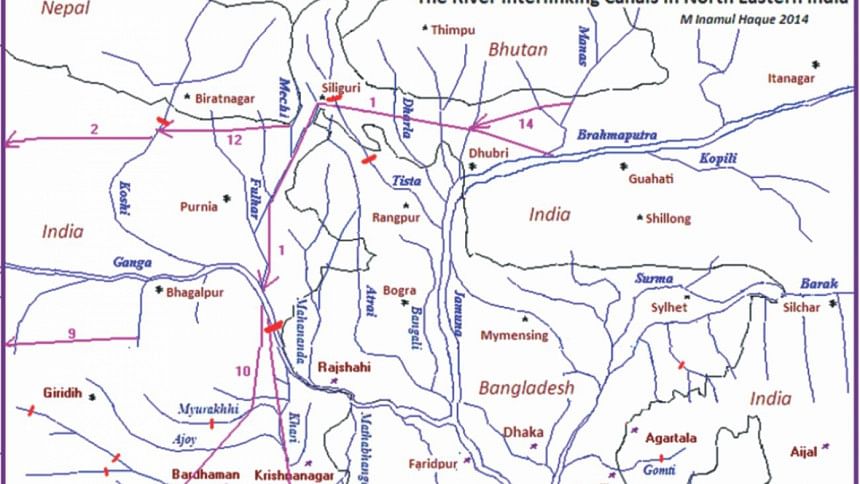

Recently, The Daily Star (July 22, 2015) reported that India will be proceeding ahead with its Rivers Interlinking Project, particularly on its northeastern part, to link the rivers Brahmaputra, Manos, Sankosh, Raidak, Torsa, Dharla, Teesta, Mahananda and Mechi. These activities refer to the planned canals No. 14 and 1 of the Rivers Interlinking Project, which are to crisscross through western Assam, North Bengal part of Paschimbanga and eastern Bihar (see the map). The Indian Water Resources Minister Sanwar Lal Jat has said, "This link project will not only provide large irrigation and water supply benefits to Assam, West Bengal and Bihar but will also make available large quantum of water for transfer subsequently to southern states." The governments in West Bengal, Assam and Bihar will soon be approached for their consent, Jat said.

The interlink project has 30 canal systems stretching from Brahmaputra River basin in the northeast of India to the Luni River basin to the west and Cavery River basin to the south. The main issue with the interlinking of rivers is the increasing water demand in the states of India due to unhindered growth of population everywhere. According to the report published in The Daily Star, the concerned officials of India-Bangladesh Joint Rivers Commission in Dhaka expressed their unawareness of any move from the Indian side, as they were not officially reported by their counterpart. They claimed that they are "not supposed to divert water from any of the Himalayan River without the consent of Bangladesh." But the fact is, India is diverting Teesta River's lean period flows without informing or even caring about the adverse effects on Bangladesh, as evidenced during the lean periods in 2014 and 2015.

The increasing water and food demand has led to Indian states to fight with each other over sharing water from common sources. The recent creation of Telengana has not only increased administrative division, but also increased rivalry over the sharing of water. The project for interlinking of rivers offers impractical hopes to the water starved western and southern states of India.

From an engineering point of view, the interlinking project can be executed and delivered on the ground. Though possible from an engineering point of view, completing the interlinking project of such magnitude is not possible for various practical reasons. Any hydraulic mass has a natural tendency to flow downwards; the river basins are created out of that natural tendency. Any civilisation that grew on created water resources has been able to live for some decades only. The reservoirs, structures and canals that will be created under this interlinking project shall devour cultivable lands and uproot people from their homes. The diversion projects shall have high evaporation loss on exposure, high conveyance loss by seepage, etc. The structures that will be built shall fail to deliver lateral flow against gravity, leading to clogging by sand and silt, and incur high maintenance cost. The environmental impact on ecology and on animal life shall be visible both at upstream and downstream of the project components. Moreover, these projects shall have to bear huge power costs to lift the water to be conveyed against gravity. With this and other unlimited maintenance costs, there is no sound cost-benefit dynamics.

The cost of the Rivers Interlinking Project in 2005 was Rs 560,000 crore; by now it has increased threefold. However big the investment figure might be, investors like the World Bank and the ADB are reportedly ready to invest in this project. State governments of India, particularly, Assam, Paschimbanga and Bihar are opposing this project. But the central government of India has the power to start this project anytime and anywhere they please. In that case, the states may voice their opposition through their people, politicians and activists.

There are reports that the Bangladesh government is likely to send a note verbale to India. It will be a matter of joy if the authorities concerned take up the matter of unilateral withdrawal of Teesta waters from the past, as they oppose any future withdrawal unless an agreement is settled upon.

The commentator is Chairman, Institute of Water & Environment.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments