Pawn Power

Bob Dylan's timeless 1964 song Only a Pawn in Their Game about the assassination of Medgar Evers, the black civil rights activist from Mississippi suggests that Evers' killer is not solely responsible for his crime as he was only a pawn of the rich white elite. Dylan is one of the greatest singers of all time. But his assumption that pawns are powerless is erroneous. We will come to that later.

In its heyday, world stopped for professional chess. US Grandmaster Bobby Fischer, the 11th world champion and probably the most eccentric player ever, ventured Muhammad Ali-like predictions about upcoming tournaments. Millions watched him take on the Soviet Union's Boris Spassky, the 10th world champion, between 1960 and 1972, symbolising the Cold War. In the 80s and 90s the famous rivalry between Kasparov and Karpov was seen as a clash between the old and the new guard of the crumbling Soviet Union. The moves of their epic 1984-1985 battle for world supremacy were published in the Daily Sangbad for followers who would analyse them and engage in the logic-chopping of who was the stronger of the two.

We lost that momentum long ago. The absence of charismatic players along with Chess Federation's financial and other problems have all played a part in what at first glance may look like chess's march to oblivion despite having a decorated history in the region.

Mir Sultan Khan (1905-1966) from a small village near Sargodha, Pakistan, an errand boy of Nawab Sir Umar Hayat Khan, took the chess world by storm by winning the all-India Chess Championship in 1928 and then the British Championship three times (1929, 1932, 1933). His most famous win came at Hastings (1930-31) against Cuba's José Raúl Capablanca, one of the greatest chess players of all time. Surprisingly, another "servant" of Sir Malik, known as Miss Fatima won the British Ladies Championship in 1933. And in recent times, Viswanathan Anand, a five-time World Champion, has made chess a household name in his native India where the game is believed to be originated from.

In Bangladesh, National Professor Dr Qazi Motahar Hossain (1897-1981), is regarded as the pioneer of chess, winning the all-India chess championship seven times. The saint-like scientist and statistician was the founder-president of the All Pakistan National Chess Federation in 1969. After independence, he was also the founder-president of the Bangladesh Daba Sangha, which in 1974 became the Bangladesh Chess Federation.

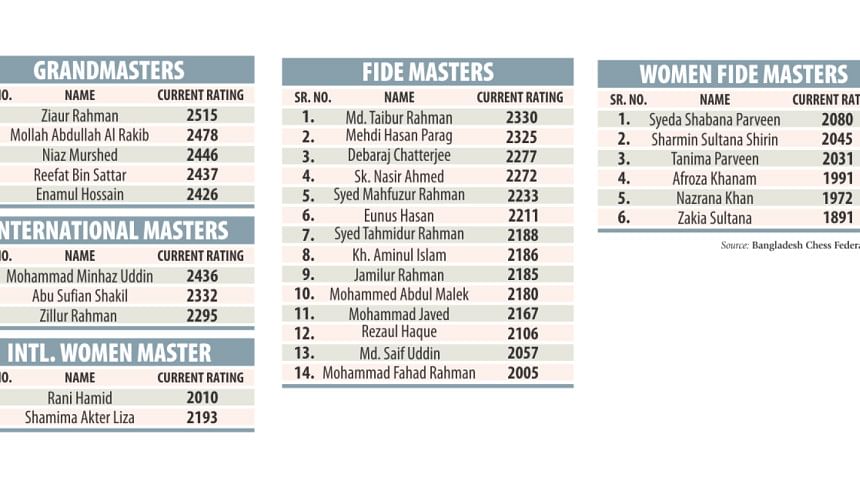

This illustrious tradition continued with Niaz Murshed becoming a Grandmaster (GM) in 1987—the highest title a chess player can attain—as the first South Asian, and two years before that, Rani Hamid winning the Woman International Master (WIM) title. Since then four more Bangladeshi men and a woman have earned that distinction respectively.

Unfortunately, these achievements have done little to raise the profile of the professional game. "The national team that was formed 20 years ago is still playing," says Niaz Murshed. "I shouldn't be here. It's like Nannu, Atahar and Akram still playing in the national cricket team. Chess is a child-prodigy game. For a long period of time we have not been able to produce any grandmasters."

This inability has complex origins. Syed Shahab Uddin, a vice-president of the Bangladesh Chess Federation says, "We get only Taka 16-17 lakh annually from the government. We have a serious space constraint. When we organise rated tournaments, we cannot accommodate all the players in our match room. Some players have to sit in the veranda."

Chess players reach their peak at a very early age and that's why the cultivation of the game should start at the school level. Take for example, Mohammad Fahad Rahman who in 2013 became the youngest FIDE Master of Bangladesh at the age of 10. The young genius first gained attention in 2011 by beating the GM Ziaur Rahman Zia in a friendly duel in just eight minutes.

It makes a nice story but reveals little about the sacrifice his parents had to make for their prodigious son. Md Nazrul Islam, Fahad's father, quit his job as an English teacher in Modhukhali Women's College and came to Dhaka to support his son. His mother, Hamida Khan is a former national women chess player. Fahad practices 7-8 hours every day. The country has many more untapped prodigies like him, experts believe.

Critics gripe about mercurial decision-making within the Federation. Rani Hamid says, "We are going to the Chess Olympiad in Russia in September. No training camp has been set up yet. Last year when I went to Delhi to participate in the Commonwealth Chess Tournament, the Federation did not even give me a ticket. The National Sports Council gave one on special consideration. I won the trophy. I have brought home the British Gold medal and so many other prizes but haven't received any financial rewards from anywhere. Promising players should be given decent jobs so they can concentrate on improving their game and participate in tournaments. It's common practice in India."

Despite all these limitations, Bangladesh ranks among the top 60 countries in the world, according to Haroonor Rashid, member of FIDE Arbiters' Commission and an international arbiter. "The promotion of chess has to be done in three tiers: Talent hunt at the school level, creating opportunities for mid-level players to play in rated tournaments and making sure that top players participate in major international tournaments and youth tournaments. One has to practice 16 to 17 hours a day. It's like preparing for the SSC exam." Rani Hamid suggests that it should be included in school curricula and the Federation should make it compulsory for every club to have at least one woman player.

If not grooming Grandmasters, chess programmes have other benefits for youngsters. Educators believe chess stimulates students' cognitive skills and help them develop social skills that can contribute to an enhanced sense of self-esteem. With chess, children can practice deductive reasoning and use it in day to day situations. Niaz Murshed says, "It helps develop concentration, strategy, foresight, patience and analytical skills. Studies show that elders who play chess have lower risks of developing Alzheimer's. In fact, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed saw this news and encouraged me to set up a chess club in BRAC University last year. Since then a lot of other universities have approached me. Schools should follow this example."

Strategy is the key in chess and increasingly, players are relying on computers to sharpen it up. The number of possible moves in a chess game is dizzying, more than the number of atoms in the universe and programmers are writing progammes to "solve" chess, considered the king of all games. Players in major chess playing countries now spend long hours playing with computers instead of humans. Rani Hamid says, "Players are becoming machine-like which I don't like. I miss the human touch." She reminds me of Dutch grandmaster Jan Hein Donner, who, when asked what strategy he would use against a computer, jokingly said, "I would bring a hammer."

Things are improving but slowly. In October 2015, Mahindra Comviva, the global leaders in providing mobility solutions, signed a sponsorship agreement with Fahad, the gifted youngster to provide support in his quest to become the youngest Grandmaster of Bangladesh. "I want to become the number 1 player in the world," Fahad says. Professional players and long time followers of the game opine that more sponsors should come forward. "But it's not easy," Niaz Murshed says. "Chess gets very little coverage in the media. Very few understand the game. Perhaps companies can do it from a CSR perspective."

Getting back to Dylan's song, pawns are not powerless at all. Not in chess or in life. In fact, a pawn that reaches its eighth rank can immediately be changed into the piece of choice: a queen, knight, bishop or rook.

And in life, people may seem like pawns, helplessly watching things happen.

But we forget they are also the ones who make things happen.

The writer is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments