Cultural construct of Pahela Baishakh

Pahela Baishakh has its roots in the simple custom of cooking good food and taking it with fish and vegetables followed by some sweetmeats. This predominantly agrarian practice was common among the peasants in antiquated Bengal following harvesting of new paddy.

Though a school of historians believe King Shoshangko of Gour should be credited with starting the Bangali era, commonly it is believed that Mughal Emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar introduced a revised Bangali calendar (1584 A.D.) to facilitate tax collection in Bengal. The farmers of Bengal found it convenient as it was the time when they harvested a rich yield of paddy. Till then it was limited to the mundane rituals of farming, harvesting and husking.

Soon, the month of Baishakh was selected by the 'boniks' or businessmen of Bengal to close account books of the previous year and open new ones, hence we saw the introduction of the custom called 'halkhata' throughout Bengal. Shop owners of old Dhaka and Narayanganj (as well as those in other district towns) used to offer sweetmeats to everyone who stepped inside their shop on the first day of Baishakh. Traders and customers used to come with cash to pay off all credits on that day and leave smiling devouring plenty of roshogollas. Today's commercialisation of the day has its roots in the halkhata tradition of the yesteryears.

Pahela Baishakh was never a big cultural festival in Bengal in the '50s or '60s therefore it would be difficult to define or analyse its cultural construct, as we observe it today. Before the birth of Bangladesh, there was no centrally organised Pahela Baishakh festival, no rally with masks, no indulging in ilish-panta and so on. In some parts of old Dhaka and in district towns small melas used to spring up spontaneously where mostly women used to throng for glass bangles and children for sweets and clay dolls.

It was since the mid '60s that Pahela Baishakh began to take the character of a cultural festival with the opening of the day with Tagore songs at the Ramna Botomul (Banyan tree) under the stewardship of Chhayanaut, the leading cultural organisation of the country. The decision was taken by the cultural stalwarts of the time in defiance of the banning of Tagore songs on radio by the then pro-Pakistani authority. The festivity at Ramna ground was limited to singing songs of Tagore, DL Roy and others, the theme of which were mostly about love for the country and Bangali nationalism. A small number of vendors used to sit in front of the High Court to sell bamboo flutes, glass bangles, food items and clay dolls.

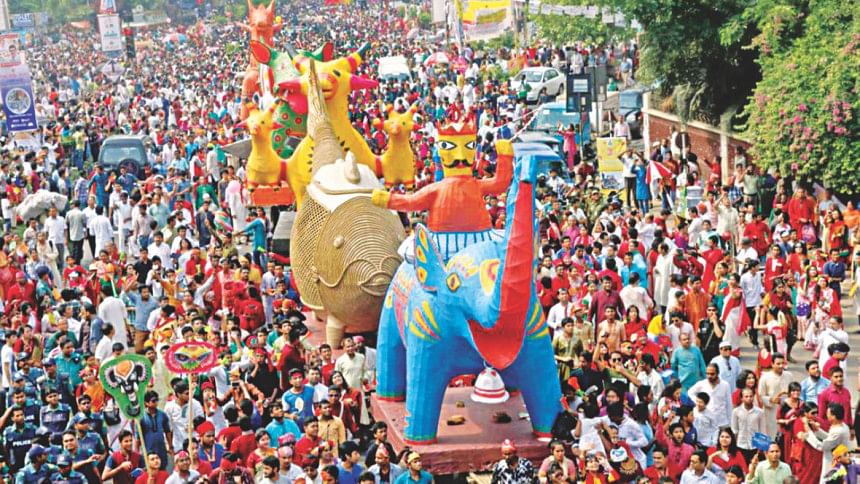

Gradually, as more and more people, predominantly literate middle class, started to join in the early morning musical soiree at Ramna, teachers and students of Charukala Institute came up with the idea of starting a carnival type rally to go around the Dhaka University campus carrying bamboo and cloth made larger than life animal figures to add colour to the event. Roads were decorated with alpana on the roads, traditional designs depicting Bangali motifs. It became a big attraction for Bangalis coming from all walks of life. The number of people attending the rally swelled every year and today it has become a law and order situation for the administration.

The cultural construct has evolved slowly over the decades, to display loudly the rich cultural heritage of Bengal before the world. Interestingly, the Pahela Baishakh festival is the only of its kind that has no religious flavour to it. It is hundred percent secular where Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Buddhists join spontaneously. Recent years have seen an influx of people of other nationalities joining the rally to enjoy the extravagance.

True, many later day customs or rituals have been added to the festivity, like savouring ilish and panta early in the morning, but culture is not something that remains stuck with one or two things. It picks up many new things on its way while leaving many things behind. That is the beauty of Pahela Baishakh in Bengal.

But, last year, some ugly incidents greatly marred the spontaneous celebration of this event. Also use of foreign made shrill horns robbed the rally of its local culture. In response to that, this year the Ministry of Home Affairs has announced some dos and don'ts for the day albeit to the dismay of the organisers. Law enforcers do not want masks to be used in the rally for security reasons. It wants the whole event to come to an end by 5 in the afternoon. No one will be allowed to stay on the campus after dusk.

There is mixed reaction from the civil society to these directives. A group welcomes the decisions whereas others believe it is a denial of one's rights. Instead of putting restrictions, the latter group wants better management by the organisers with more volunteers on the ground and presence of law enforcers on the sidelines so that they can come to the rescue of victims of assault, if any.

There is scope to improve the management of the rally. It can be organised on a bigger premise instead of the narrow road in front of the Charukala building. The number of volunteers can be increased and they can be given better training on such matters. We believe the number of close circuit TVs should be increased on the entire route the rally will pass through. And lastly, no big group of young men should be allowed to move in a body aimlessly. Instructions could be given that rows of men and women keeping enough space between two rows will have to walk uniformly not breaking away from one another. For better visibility more floodlights could be installed on the entire route. Pahela Baishakh comes only once a year with the messages of love and freshness. Therefore, let us welcome it with a pure heart vowing not to turn the merriment of others into an occasion for moaning.

The writer is Editor, Special Supplements, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments