In sight but out of mind

This year Bangladesh exceeded all expectations, achieving a GDP rate of over 7 percent. With higher growth, the issue of labour rights is also gaining prominence in our national discourse, with more and more emphasis being given on workplace safety and wellbeing. Those amongst us who are educated are becoming more and more aware of our rights in our workplace, as we unhesitatingly demand for better pay, better facilities, a better life, really. And why shouldn't we? This is our right as promised by our Constitution and by our state. But there still remains a large portion of our workforce, over 80 percent to be precise, who are not warranted recognition by any of our state apparatuses. When we talk proudly of progress and development, we tend to take for granted that only those who fall under a formalised structure deserve acknowledgement and thereby can demand their rights under the law. We choose to ignore more than half of Bangladesh's population who, despite their indispensible contribution, are regarded as expendable, replaceable, and thus, undeserving of formal rights or protection.

In Asia, the informal economy accounts for 78.2 percent of total employment. It's ironic that in a world which still depends on informal employment to run their economies, those working in this sector continue to be treated as necessary but unacknowledged and invisible clogs of society. There is a not-so-subtle disdain for those who make our beds or build our homes; we choose to ignore that as human beings they too might have the same concerns and needs as the rest of us. Most people enter the informal economy because they have no other means to sustain themselves, with no education, skills or capital to participate in the formal workforce. But this does not mean that the risks associated with their work is only theirs to accept; the employment of workers in the informal economy, including housemaids, agricultural labourers, construction workers, day labourers, fishermen, vegetable vendors, etc, might be self-managed but the services they provide is universal.

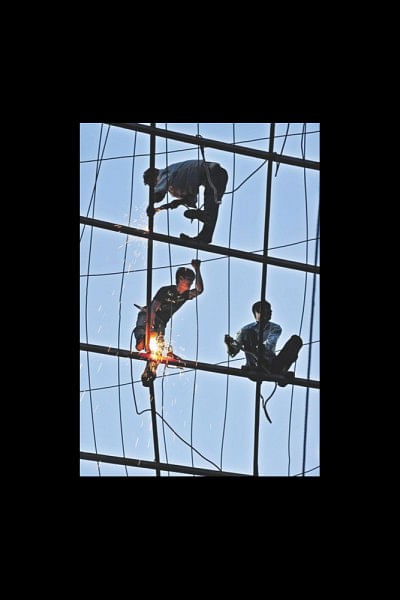

While those working in the informal economy are not even recognised as 'workers' in the Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006, the Informal Sector Survey 2010 by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics asserted that the informal sector was the major source of employment in the country, amounting for 89 percent of the total jobs. As self-managed employment is socially unrecognised as work, it becomes easier for workers to be exploited. Thus, you hear of the brutal murder of 13-year-old Rakib Hawladar, whose former employer killed him in an inexplicably violent manner when he switched jobs. You regularly read stories of construction workers falling to their deaths, due to the lack of safety gears or adequate protection. How many times have you looked up a building to see a person dangling from a scaffolding, with nothing but a rope as a measure of safety? Every time I look up at them, I am overpowered by a sense of dread, and am forced to look away after a few minutes when I start feeling dizzy; but these people continue doing their work in the only way they know how to – with confidence galore and little attention to the risk that they are putting themselves in.

Accidents and deaths on site go largely unreported; in the rare occasions that the death of a worker is reported, there is no follow-up from the police, government, media or their own families who, in their struggle to make ends meet with one less earning member, are unwilling to demand compensation that they will not get or go to the court where their voices will be muffled.

A report published by the Asian Development Bank stated that unlike employees working under a formalised structure, workers with irregular employment don't have any specified working hours, as they often have to work an average of 54 hours a week "with non-commensurate compensation." Workplace safety is practically unheard of in the informal economy, and there's no question of holidays, sick days or downtime. Brick kiln and construction workers have scarce drinking water and no toilet facilities to speak of. With wages being disbursed on a daily basis and no bargaining power with employers, they rarely take days off even when they suffer from ailments resulting from having to work long hours in intense heat. Let's not talk about education or training opportunities, which cannot even be regarded as luxuries in a sector that is not officially recognised by the law.

Given the dearth of official data, it is difficult to even ascertain the particular health problems faced by people working in the informal economy. However, according to a report titled 'Health Vulnerabilities of Informal workers' by the Rockefeller Foundation, there is increased risks of malnutrition, physical and psychological disorder, respiratory trouble, heart attack, etc, due to the nature of their work, where they are forced to endure excessive labour, and an unhealthy work environment. More than a million workers who work in the brick kilns of the country, which produce over 12 million bricks a year, often suffer from skin diseases and are susceptible to bronchial infections. As per the report, workers often take drugs "to boost their physical and mental energy" when their body no longer supports their need to earn a livelihood. Rickshaw pullers, for example, are addicted to various drugs as these help them deal with the intense temperament of their work.

Article 15 of Bangladesh's Constitution ensures guaranteed employment, work with reasonable wage, recreation and leisure for all workers, while Article 20 argues that employment should be a right for every citizen, insisting that workers should be "treated with justice." Moreover, Article 10 prohibits social exploitation of any worker. However, in this case, there seems to be a clear divide in the treatment of those who are considered "actual workers" and the unrecognised millions who simple cannot be brought under a structure, thereby making it impossible to ensure them the same rights reserved for everyone else. Equality, once more, becomes a tool to bandy around when talking about the achievements of our country and its legal apparatus.

In fact, the Domestic Workers Protection and Welfare Policy 2015, one of the few measures taken to prevent the exploitation of a segment of the workers of the informal economy, is still to be implemented, even though a draft of the policy has already been approved by the cabinet.

There is an urgent need to change our perception toward informal workers, which can help bring a shift in the way they are treated in law and policy. We need to introduce a feasible wage structure, which runs parallel with their working hours and is in sync with their work environment. Moreover, experts have also stressed the need for a pension/insurance scheme, something that has already been undertaken by the Government of Delhi in September 2013 for the informal workers of India. As suggested by lawyer Kawsar Mahmood in a piece he wrote for the Dhaka Law Review, this will offer security for workers in the informal economy during their sickness or after they retire from work. "On registration, workers will be saving a portion of their income per month or per annum in a provident fund where the government will equally contribute," he writes.

As human beings, we have the right to demand better pay, better working conditions and fair treatment from our employers. It'll be a shame if this right continues to be reserved for some of us, while the majority are left stumbling, persisting through life as nameless, faceless beings.

The writer is a member of the editorial team, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments