Kepler telescope discovers 100 Earth-sized planets

Nasa's Kepler telescope has discovered more than 100 Earth-sized planets orbiting alien stars.

It has also detected nine small planets within so-called habitable zones, where conditions are favourable for liquid water - and potentially life.

The finds are contained within a catalogue of 1,284 new planets detected by Kepler - which more than doubles the previous tally.

Nasa said it was the biggest single announcement of new exoplanets.

Space agency scientists discussed the new findings in a teleconference on Tuesday.

Statistical analyses of Kepler's expanding sample of worlds help astronomers understand how common planets like our own might be.

Dr Natalie Batalha, Kepler mission scientist at Nasa's Ames Research Center in California, said calculations suggested there could be more than 10 billion potentially habitable planets in the Milky Way.

"About 24% of the stars harbour potentially habitable planets that are smaller than about 1.6 times the size of the Earth. That's a number that we like because it's below that size that we estimate planets are likely to be rocky," said Dr Batalha.

"If you ask yourself where is the next habitable planet likely to be, it's within about 11 light-years, which is very close."

Future observatories such as the James Webb Space Telescope could examine starlight filtered through the atmospheres of exoplanets for potential markers of biology.

"The ultimate goal of our search is to detect the light from a habitable exoplanet and analyse that light for gases like water vapour, oxygen, methane and carbon dioxide - gases that might indicate the presence of a biological ecosystem," said Paul Hertz, director of astrophysics at Nasa.

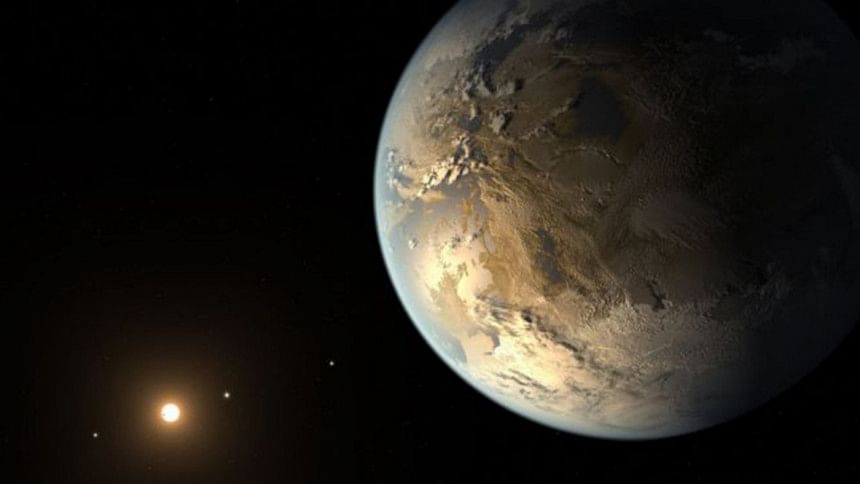

Of the telescope's finds to date, the planets Kepler-186f and Kepler-452b are arguably the most Earth-like in terms of properties such as their size, the temperature of their host star and the energy received from their star.

Dr Batalha said the new finds Kepler 1638b and Kepler-1229b were intriguing targets in the search for habitable planets.

The Nasa Ames researcher said the Kepler mission was part of a "larger strategic goal of finding evidence of life beyond Earth: knowing whether we're alone or not, to know... how life manifests itself in the galaxy and what is the diversity".

She added: "Being able to look up to a point of light and being able to say: 'That star has a living world orbiting it.' I think that's very profound and answers questions about why we're here."

Dr Timothy Morton, from Princeton University in New Jersey, said the overwhelming majority of exoplanets found by Kepler fell into the super-Earth (1.2-1.9 times bigger than the radius of Earth) and sub-Neptune sized (1.9-3.1 times bigger than Earth's radius).

He noted that planets in this size range had no known analogues in our Solar System.

Scientists used a new statistical technique to validate the 1,284 new exoplanets from a pool of 4,302 targets from Kepler's July 2015 catalogue of planet candidates. The technique folded in different types of information about the candidates from simulations, giving the astronomers a reliability score for each potential new world.

Candidates with a reliability greater than 99% were designated as "validated planets".

The team identified a further 1,327 candidates that are more likely than not to be planets, but do not meet the 99% threshold and will require further study.

Kepler employs the transit method to detect planets orbiting other stars. This involves measuring the slight dimming of a star's light when an orbiting planet passes between it and the Earth.

The same orbital phenomenon was involved when Mercury passed across the face of the Sun on Monday.

The Kepler telescope, named after the Renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler, was launched on 7 March 2009.

In May 2013, the second of four reaction wheels - used to control a spacecraft's orientation - failed on Kepler. This robbed the orbiting observatory of its ability to stay pointed at a target without drifting off course.

However, engineers came up with an innovative solution: using the pressure of sunlight to stabilise the spacecraft, allowing it to continue its planet hunt. The resulting mission was dubbed K2.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments