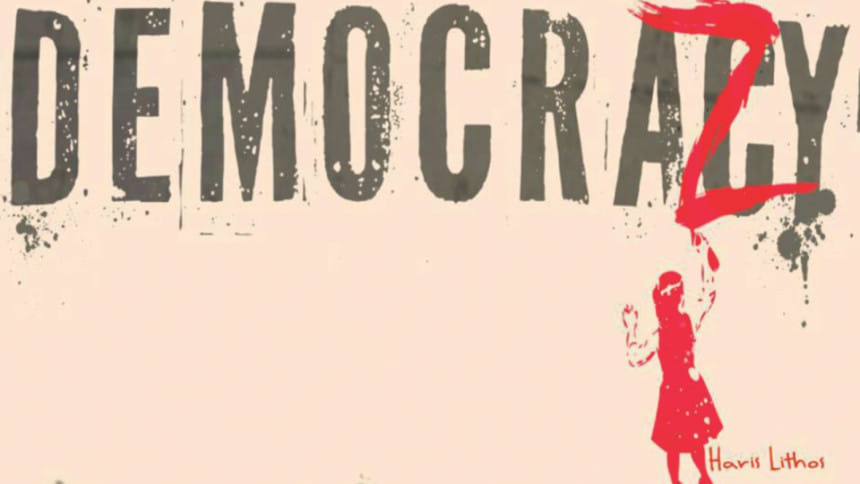

If our democracy could talk, what would it say?

Does our democracy bleed when 12 people are killed in just one phase of UP elections? Does it reek of half-rotten flesh of the masses, of mouldy dreams and broken promises? Does it feel ashamed, weary, angry, when, in its name, school children are shot dead, and youth tortured, in broad daylight, shamelessly, unapologetically, with impunity? When, in its name, more than a hundred are reportedly killed in the first four phases of UP elections, 40 of them AL activists, 12 supporters of rebel AL candidates, two BNP men, and the rest, ordinary citizens with no stake in the elections beyond that of, yes, a citizen? Does democracy cringe in humiliation when opposing candidates are prevented from filing nomination papers, ballot boxes are stuffed and voting centres taken over by force as we [continue to] sing the eulogies of a 'free and fair' election? Does it find itself drowning in a perplexing time warp, with the past, present and future collapsing onto each other, with history repeating itself, over and over, albeit in new(er) forms, the boundaries between heroes and enemies blurred more than ever?

Does our democracy remain unmoved when, in the remote areas of Bandarban, in Thanchi upazila, some 1,500 people starve, living on nothing but scarce forages from the forest? We can only assume that it is indifferent to the rancid hypocrisy of celebrating high GDP growth and our promotion to a lower-middle income country status, while famine grips the Jumma people, who have been driven from land to land, hills to hills, forest to forest, over generations, by settlers, corporations and the state, to the absolute margins. Democracy, we fear, feels no shame at all that it deploys the rhetoric of development to justify state-sponsored aggressions over adivasi land, building eco-parks, science institutions and resorts that the communities to whom the land really belongs don't want, all the while ignoring the real issues that 'development' – inclusive, people-oriented development – should do, like ensure food security, land rights, sustainable livelihoods, education and healthcare.

The state, in the curious form it takes in the CHT, is present everywhere, yet it was ostensibly missing in action when it came to taking proactive and effective measures to tackle this near-famine in an area that it knows is prone to food crisis; what is worse, it remains, still, apathetic to the plight of the people of Thanchi, content to have sent token supplies of rice to the afflicted communities – all of which, in all likelihood, would not even reach the beneficiaries, thanks to our national tradition of corruption, irregularity and mismanagement. The food crisis and the state's reaction to it highlights what is pretty obvious by now to those who are abreast of what goes on in the CHT – that when one talks about development, it is certainly not that of the poor, indigenous communities whose lives are more precarious than ever, with hardly any of the major pledges of the 1997 Peace Accord fulfilled. And when people resist what the government would like to wholesale, impose, or force-feed as "development", democracy seems quite at ease to quell people's resistances, violate pledges and dismiss the age-old demands of the adivasi communities; it sees no conflict at all with democratic principles that, in the CHT, it's not 'of or for the people' but 'of and for Bengali settlers.'

Does democracy, we wonder, suffer from an existential angst when movements, not just in the CHT but plainlands too, from Bashkhali to Rampal, from Savar to Habiganj, are suppressed, at times by armed goons with political clout, at times by law enforcement agencies themselves, and at others, by corporations with enough money and power to buy the first two? Maybe it does, or maybe it has found a way to gloss over the repeated warnings from experts and national and international environmental organisations about the irrevocable dangers of building power plants in ecologically sensitive areas, to ignore the cries of the tea workers who are being evicted by the Holy Trinity of goons-state-corporations from the land on which they have sweated for generations, to justify the murder of villagers fighting to save the environment and, along with it, their lives and livelihoods, and to perpetrate widespread violence on and arbitrarily arrest, threaten, harass, even kill, those who challenge what they deem as anti-people state projects. It's not a new phenomenon, to be sure – democracy's weakness towards protecting the interests of Capital—but its allegiance to Capital and Corruption has perhaps never been so unapologetic, so aggressive, so ruthless.

Does democracy mourn the disfigurement of the free media, the demise of intellectualism, the maiming of critical thought and freedom of expression? Does democracy lament the standardisation and neutralisation of dissent, be it through successive murders by Unknown Assailants, discourses that justify proliferation of hatred and violence and repressive laws that curtail already shrinking spaces for free thought?

Dear democracy, I no longer know what you feel, think or want; you're no longer something I am familiar with, something I can trust. I don't expect you to be perfect, but I do wonder: do you recognise yourself in the mirror? Do you even know what you stand for, anymore?

The writer is an activist and journalist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments