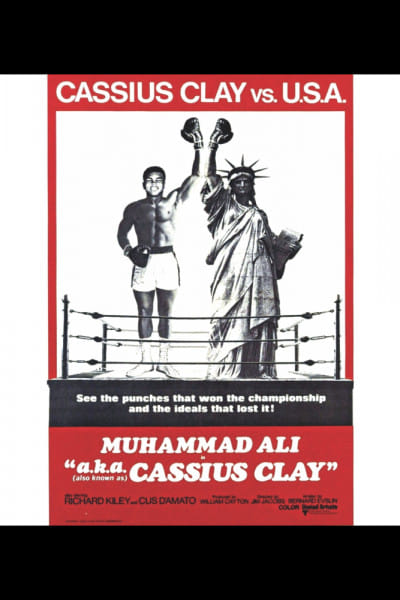

Ali won in the court Ali won in the ring

When Muhammad Ali Clay made entrance onto the scene in 1960 he was an 18-year-old amateur boxer with brashness and youthful exuberance. From the beginning he transcended boxing, making bold predictions—usually correct—about what round he would stop his opponents in; his hilarious doggerel poetry was recited by school kids who had never seen a boxing match.

For many of us Muhammad Ali was a childhood role model, an exemplary Muslim, a striving athlete, and a fighter who refused to shed blood. As we mourn his loss today, we also reminisce his outspokenness, his somewhat blunt way of saying what the truth is. We briefly speak of the case that set his stance for righteousness, the case of Clay v United States

The premise of the case is set by Ali's declaration that he would refuse to serve in the U.S. Army for the ongoing Vietnam War and publicly proclaiming himself a conscientious objector. Stating wars are against his religious belief, he took his stance by famously saying: "I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong ... They never called me nigger."

His conscientious objector application was rejected by the draft board of Louisville, Kentucky. On appeal, The Justice Department advised that Ali's claim should be denied, as according to their opinion, Ali did not meet any of three basic tests to avail such status. The Appeal Board complied, never stating any reason.

In 1967, Ali tried reclassifying his appeal as a Muslim Minister, which too was denied by 4-0 by the federal judicial district. He had to for his scheduled induction into the U.S. Armed Forces in Houston on April 28.

Ali refused three times to step forward at the call of his name. An officer warned him he was committing a felony punishable by five years in prison and a fine of $10,000. Once more, Ali refused to budge when his name was called. As a result, on that same day, the New York State Athletic Commission suspended his boxing license and the World Boxing Association stripped him of his title. Other boxing commissions followed suit. He was indicted by a federal grand jury on May 8 and convicted in Houston on June 20. The trial jury was composed of six men and six women, all of whom were white. The Court of Appeals affirmed and denied the appeal on May 6, 1968.

The Supreme Court held that, since the appeal board gave no reason for the denial of a conscientious objector exemption to petitioner, and it is impossible to determine on which of the three grounds offered in the Justice Department's letter that board relied, Ali's 1967 conviction must be reversed. The Supreme Court decision was handed down on June 28, 1971.

In their book the Brethren, author Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong provided an account of the development of the case. According to that account, Justice Marshall had recused himself because he had been U.S. Solicitor General when the case began, and the remaining eight justices initially voted 5 to 3 to uphold Ali's conviction. However, Justice Harlan, assigned to write the majority opinion, became convinced that Ali's claim to be a conscientious objector was sincere after reading background material on Black Muslim doctrine provided by one of his law clerks. To the contrary, Justice Harlan concluded that the claim by the Justice Department had been a misrepresentation. Harlan changed his vote, tying the vote at 4 to 4. A deadlock would have resulted in Ali being jailed for draft evasion and, since no opinions are published for deadlocked decisions, he would have never known why he had lost. A compromise proposed by Justice Stewart, in which Ali's conviction would be reversed citing a technical error by the Justice Department, gradually won unanimous assent from the eight voting justices.

The writer works at Law Desk.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments