Rise of regional political parties in India

The recent States Assembly Elections in five states of India indicate that Indian voters are becoming more region-centric. In three states - West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala - people have rejected national level parties, opting instead for regional ones. The BJP-led alliance succeeded in Assam while the Congress-led coalition won in Puducherry.

Today, out of India's 29 states, the Indian National Congress (INC) led alliances have six states and BJP led coalitions are in nine states. The rest 14 are ruled by regional parties. As of 2015, the Election Commission of India recognises only six national parties, 62 state parties and 1,737 registered but unrecognised parties in federal India. Among the six national parties, only two have presence all over India – the Congress and BJP. The four other national parties are basically state parties – the CPI, CPI(M), Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and National Congress Party (NCP), although they have contested national elections from more than one state.

Since the Partition of 1947, Congress has had total sway over the political scenario of India until 1996. There were of course two brief interruptions – once from 1977-79 by Janata Party (Morarji Desai) and again from 1989-90 by the Janata Dal (V.P. Singh). The turning point in Indian election politics came in 1996.

The 1996 general election produced a fractured verdict for the 11th Lok Sabha, when for the first time BJP dethroned Congress and A.B. Vajpayee became the prime minister for 13 days. After BJP failed to pass a confidence motion, 13 regional parties formed the United Front that lasted two years. Since 1996, all central governments in Delhi have been coalition governments, either led by Congress or by BJP. Clearly, the days of a single party forming the government at the centre was over, and coalition governments became the order of the day.

INC's struggle for independence, its socialistic economic orientation, secularism and its non-aligned foreign policy had lasted in people's mind for the first three decades after independence. As India consolidated its place in the comity of nations, people's aspirations for development overtook the sense of nationalism and gave into provincial aspirations. And as the Cold War receded in the early 1990s and globalisation undermined India's socialistic policies, Congress started to lose its appeal among the vast population of India. Besides, the litany of scandals and allegations of corruption also played a role in people's disenchantment with Congress. Currently, the party is in doldrums, continuing to carry the baggage of the Nehru dynasty.

The conservative right-wing BJP came into being in 1980 with close ideological and organisational links to the Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bajrang Dal. BJP has since used the "Hindutva" (Hindu nationalism) ideal to capture the imagination of India's 80 percent Hindu population. Since the 1984 national election, BJP enlarged its vote share and also increased its number of seats in the Lok Sabha and made inroads at the state level. In 1998, it finally rode to power at the centre, riding piggyback on several regional parties.

What is revealing is that both BJP and Congress have not contested the recent State Assembly Elections on their own. They have invariably tied up with one or more state level parties. It reflects that these two national parties do not have enough vote-share in those states to go alone. Congress once did have enough votes to win state elections alone, but not anymore, while the BJP is still trying to build its vote base in the states.

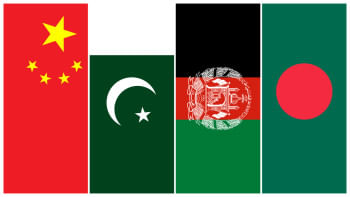

India is a vast country with 1.2 billion people, who differ from one another in language, ethnicity and social traditions. The creation of states is primarily based on language. People's demands for economic and social development have helped the rise of regional parties with particular features – for example, linguistic (DMK, ADMK), ethnic (Gorkha League, Bahujan Samaj Party), political ideology (CPIM), religious (Akali Dal), etc. Regional parties are now more powerful and play the role of king maker at both the central and state levels. Interestingly, regional parties in bordering states are also influencing Delhi's policies towards India's neighbours.

The rise of powerful regional parties, demanding more and more autonomy, has undoubtedly made democracy more palpable to the Indian mass. The process has definitely decentralised power from the centre to the states and has improved governance. But stiff competition among the parties and unholy alliances among parties which are ideologically opposed sometimes bewilder voters. The other point to note is that many of the regional parties revolve around a single politician. Once that politician retires or dies, the party loses its bearing. The death of Jyoti Basu has left the CPI(M) in West Bengal in a quandary. Analysts say that the inevitable rise of regional parties in politically fractured India is ominous to India's territorial integrity.

However, after BJP's debacle in Delhi and Bihar in 2015, there were talks among Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar (Janata Dal United), Delhi's Arvind Kejriwal (AAP) and other leaders to form a third front. Now that two popular ladies - West Bengal's Mamata Banerjee (TMC) and Tamil Nadu's J. Jayalalitha (AIADMK) - have returned to their states, there is a chance that a new front may emerge before the next Lok Sabha elections.

Regional politics will be important in the state elections in Goa, Punjab, Manipur, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, due in 2017. The roles of Mulayam Singh's Samajwadi Party, which is currently in power, and Mayawati's Bahujan Samaj Party in Uttar Pradesh will determine the move towards the third front.

Given the rising vote-share of regional parties and BJP's intolerance towards anti-Hindutva ideology, a third front is viable. In any case, the rise of regional parties has fundamentally changed the election politics of diverse India.

The writer is a former Ambassador and Secretary.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments