The man who saved Kyoto from the atomic bomb

Just weeks before the US dropped the most powerful weapon mankind has ever known, Nagasaki was not even on a list of target cities for the atomic bomb.

In its place was Japan's ancient capital, Kyoto.

The list was created by a committee of American military generals, army officers and scientists. Kyoto, which is home to more than 2,000 Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, including 17 World Heritage Sites, was at the top of it.

"This target is an urban industrial area with a population of 1,000,000," the minutes from the meeting note.

They also described the people of Kyoto as "more apt to appreciate the significance of such a weapon as the gadget".

"Kyoto was seen as an ideal target by the military because it had not been bombed at all, so many of the industries were relocated and some major factories were there," says Alex Wellerstein, who is a historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology.

"The scientists on the Target Committee also preferred Kyoto because it was home to many universities and they thought the people there would be able to understand that an atomic bomb was not just another weapon - that it was almost a turning point in human history," he adds.

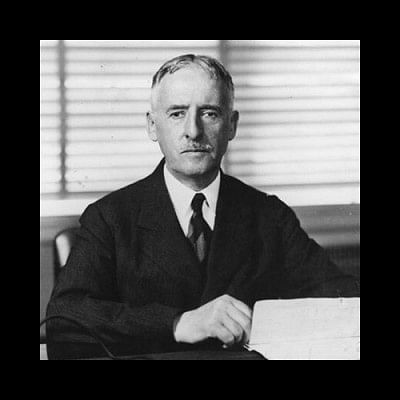

But in early June 1945, Secretary of War Henry Stimson ordered Kyoto to be removed from the target list. He argued that it was of cultural importance and that it was not a military target.

"The military didn't want it removed so it kept putting Kyoto back on the list until late July but Stimson went directly to President Truman," says Prof Wellerstein.

After holding a discussion with the President, Stimson wrote in his diary on 24 July 1945 that "he was particularly emphatic in agreeing with my suggestion that if elimination was not done, the bitterness which would be caused by such a wanton act might make it impossible during the long post-war period to reconcile the Japanese to us in that area rather than to the Russians".

Tensions that led to the Cold War were already brewing and the last thing the Americans wanted to do was bolster the Communist cause in Asia.

That was when Nagasaki was added to the target list instead of Kyoto. But Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not military targets either.

As we know today, hundreds of thousands of civilians, including women and children, were killed. And while Kyoto may have been the most famous cultural city, the other cities also had valuable assets.

"That is why it seems that Stimson was motivated by something more personal, and these other excuses were just rationalisations," says Prof Wellerstein.

It is known that Stimson visited Kyoto several times in the 1920s when he was the governor of the Philippines. Some historians say it was his honeymoon destination and that he was an admirer of Japanese culture.

But he was also behind the internment of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans because, as Stimson put it, "their racial characteristics are such that we cannot understand or trust even the citizen Japanese".

That may be partly why another man took the credit for saving Kyoto for many decades.

It was widely believed that it was the American archaeologist and art historian Langdon Warner, and not the controversial Secretary of War, who advised the authorities not to bomb cities with cultural assets including Kyoto. There are even monuments to honour Warner in Kyoto and Kamakura.

Hiroshima: The bomb that changed the world

§ The bomb was nicknamed 'Little Boy' and was thought to have the explosive force of 20,000 tonnes of TNT.

§ Colonel Paul Tibbets, a 30 year old colonel from Illinois, led the mission to drop the atomic bomb on Japan.

§ The Enola Gay, the plane which dropped the bomb, was named in tribute to Tibbets' mother.

§ The final target was decided less than an hour before the bomb was dropped. The good weather conditions over Hiroshima sealed the city's fate.

§ On detonation, the temperature in Hiroshima reached 60 million degrees, killing and injuring thousands of people instantly.

In his 1995 book, Drop the Atomic Bomb on Kyoto, Japanese historian Morio Yoshida argued that Warner was celebrated as a saviour of Japan's cultural assets as part of America's post-war propaganda.

"During the US occupation of Japan after the war, there was heavy censorship about atomic bombs," says Prof Wellerstein.

"We learned enough lessons from the previous wars about defeated enemies hating you, so any spin that would make the Japanese believe that America cared about Japan - whether the people or cultural assets - would be seen as great by the occupation authorities."

But not only did President Truman apparently care little about Japan's cultural assets, he also described Japan as "a terribly cruel and uncivilized nation in warfare," calling the Japanese "beasts" who deserved neither honour nor compassion because of the attack on Pearl Harbour.

These kinds of remarks have resulted in speculation that the US dropped atomic bombs on Japan, not Germany, because of racism - that using the weapon against white people might be seen as more of a taboo than on the Japanese.

'A personal stake'

Today, President Truman is both praised and criticised for making the call to drop the bombs.

In reality, historians say he gave the order to start using the new weapon only after about 3 August and he was not fully involved in detailed decisions.

Prof Wellerstein says there is documentary evidence that the President was surprised by the devastation caused by the first bomb, especially that so many women and children had died, and the second and more powerful bomb - that hit Nagasaki - was dropped only three days later.

That call came from the military director of the bomb project, General Leslie Groves, who led the Target Committee and lost the battle to keep Kyoto at the top of the list.

He said in a letter dated 19 July that he wanted to use at least two and as many as four atomic bombs on Japan. "You can argue that he had a personal stake in using both of the different types of atomic bombs," says Prof Wellerstein.

So, 70 years ago today, instead of thousands of temples and shrines, it was the people of Nagasaki that evaporated in the blink of an eye.

The city which was not even on the initial list of targets on the bombing order was chosen because of bad weather over the second target of Kokura city - which prevented the pilots from dropping the bomb on 9 August.

In some senses, it is perverse to claim that Henry Stimson saved Kyoto from the atomic bomb as if it was a positive outcome.

But another atomic bomb was prepared to be dropped on 19 August if Japan had not surrendered four days earlier. The third target is believed to have been Tokyo - possibly the Emperor's palace.

Today, despite the suffering that they caused, it is quite common to find people in Japan who say that the atomic bombs were needed to end the war.

But if Kyoto had been destroyed or if the Emperor was killed, perhaps not as many would be as accepting of the tragic fate that Japan suffered.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments