The Art & Politics of Documentation

For me, watching Naeem Mohaiemen's expository documentary,'Last Man in Dhaka Central', was essentially a trip down memory lane, reliving a time of hope. We are the children of the 60s who grew up amidst the great cultural movement, protesting oppression on the streets, meeting surreptitiously in study groups where professors spread the word of 'revolution', while our houses hummed with the passionate discussions of leaders of the, then, under-ground communist parties. But, Mohaiemen, as he himself asserts, specializes on the 70s and its concomitant unraveling of hope. Yet, his film exudes the ethos of optimism.

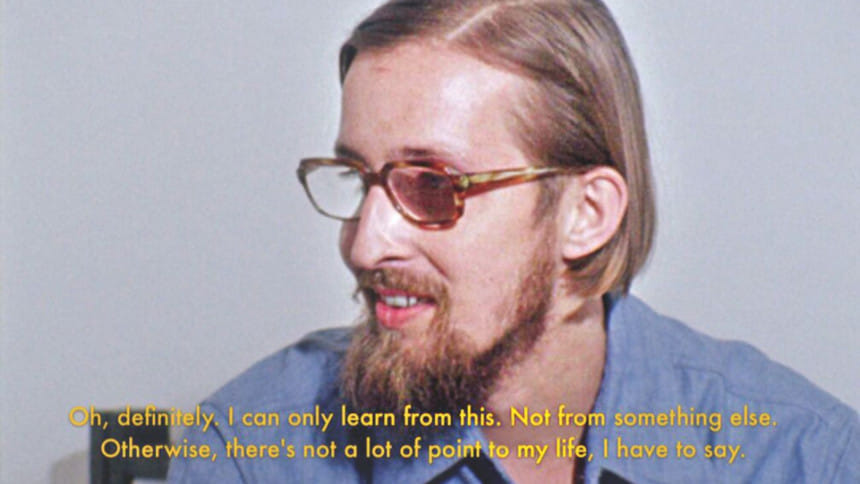

Peter Custers, the protagonist of this film, is quintessentially a romantic, symbolizing faith amidst a time of chaos. A Dutch journalist, he was jailed in Bangladesh in December 1975, accused of belonging to an underground socialist group. The documentary is based on Mohaiemen's interview of Custers. "Interviewed shortly before his death last year, 2015, at age 66, Custers reflects positively on his youthful ambition, delving into both his dreams of Marxist revolution, and the physical and psychological abuse he suffered for it." His heart full of dreams of recreating the magic of the likes of Che Guevara, Custers arrived in Bangladesh and, at some point, met up with the infamous Col. Abu Taher, who on November 7, 1975 orchestrated a socialist uprising amongst the soldiers of the Bangladesh Army. Later, Taher was arrested, tried in a secret court martial and sentenced to death. Soon after, Custers was implicated of conniving with Taher, arrested too and essentially only through diplomatic negotiations gained his freedom.

The 82 min documentary 'Last Man in Dhaka Central', echoing Scottish film theorist Grierson's account, is a 'creative treatment of actuality'. Beginning with the strains of Lucky Akhond's 'Age jodi jantam tobe mon phire chaitam', the camera rolls over Custer's little refuge, in Netherlands, packed with books, many on Bangladesh and by Bangla writers and thinkers. The initial footage, itself, sets the stage for a man recounting his life in a romantic past. While introducing the screening of the film at the ULAB Auditorium, on June 18, 2016, Liberal Studies scholar Prof AzfarHussain, quite rightly, observes that Mohaiemen uses the minimum of visual stimulation in an effort to capture the essence of the claustrophobia of Peter Custer's life - the life of a man immersed in the politics of Bangladesh, a land he was unable to interact with, unable to live in.

Almost all throughout the film voice-over narrations provide an explanatory conceptual frame- work, and images and sounds are used to illustrate and give life to the narrations. The viewer is shown details of Custer's library, including books by Tagore and Nazrul; images of old copies of the 70's magazine 'Bichitra'; press clippings of Custer's journalistic writings on his interactions with the left movement of Bangladesh - including one with the 'red moulana', Bhashani; books by the Brazilian educator Paulo Freireet al. Switching between the past and the present, the film is riveting for any student of history, in search of an understanding of the tumultuous political history of Bangladesh. On top of it all, Mohaiemen manages to add a few aesthetic twists to the cut-and-dried account, using music and finishing with interesting footage created with photographs of Peter Custer's childhood in a fairly affluent Dutch family.

Heavily scripted, Mohaiemen's film gives an overt perspective of the events through the eyes of the ambitious, but failed, left movement of the 70s. There can be no denying the archival value of the documentary. However, if any critique is to be made, it is merely an observation about the targeted audience of political documentaries like these. As materialist feminist Paula Rabinowitz points out, "Radical reportage and documentary films often provide the Left, or its various subcultures, with a self-understanding. It represents itself to itself ". Though, personally having been thoroughly captivated with 'Last Man in Dhaka Central', as I left the auditorium, I wondered if it could reach beyond the niche viewer and provide a much required perspective of history outside the narratives of the establishment.

The author is a Dancer, Cultural Activist and Researcher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments