The devil in development

The word "development" - eliciting as it does grandiloquent notions of progress - has become, at least in Bangladesh, something of a red herring. It is used as a catch-all phrase to justify just about anything — from eviction of slum-dwellers to make way for high-rise housing projects to forceful grabbing of ancestral lands to build eco-parks and tourism spots, from rampant deforestation of our woodlands to unapologetic pollution of our rivers, from undemocratic and top-down imposition of anti-people projects to suppression of dissent through violence both sponsored or otherwise. It matters little that such so-called development only exacerbates the extreme vulnerabilities of people already on the margins, destroys scarce natural resources and intensifies the ever-widening gap between the haves and the have-nots; that it does precisely the opposite of what "development"—real, pro-people development—ought to do. If one protests these actions as unjust, undemocratic or inequitable, one can be easily dismissed as being "anti-development", and by extension, "unpatriotic", making it ever more difficult to have any sort of constructive conversation about Bangladesh's development priorities (or the lack thereof).

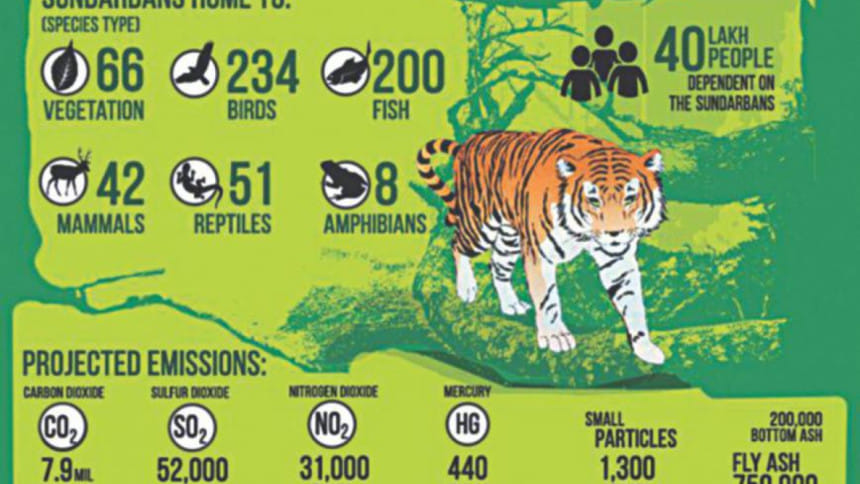

And, thus, in the name of "development", we are now witnessing an unprecedented attack on one of our most valuable natural resources, the Sundarbans. (I say unprecedented not because other regimes have not tried to sell off our natural resources to multinational corporations at a fraction of the real cost to the country, but because no prior case has involved as ecologically sensitive an area as the Sundarbans.)If development was the real goal of the construction of the Rampal power plant, if people were the focus of this intervention, why would the government displace thousands of people from their homesteads without so much as following the proper rehabilitation procedures? Why would they jeopardise, in one broad stroke, an entire ecosystem of the world's largest mangrove forest, and the source of livelihood of around 40 lakh people? Why would they discount the grave ecological danger of the construction of this coal power plant, when national and international environmental experts, including Unesco and Ramsar ("Protecting the Sundarbans is our national duty", TDS, March 22, 2016), have made it abundantly clear that this would be nothing less than a suicidal move for Bangladesh? Why would they risk our national heritage without even conducting a fair, independent and scientific Environmental Impact Assessment (for a more comprehensive criticism of the current EIA, please refer to "Sundarbans under Threat," TDS July 25, 2016)?

What gives a government the power to be so reckless when they are not the owners, but rather the guardians, on behalf of the people, of Bangladesh's natural resources?

For those who consider "environment" to be a "soft" issue that has no place in the more "grave" and "grown-up" discussions on development, let's talk economics. Let's talk about the fact that three French banks and two Norwegian pension funds pulled out their investment last year from the Rampal power plant because the "failure to comply with minimum social and environmental standards and the corresponding financial risks made the project a clear 'no-go' for financial institutions." Let's talk about the economic reality that Bangladesh will be financially responsible for 85 percent of the project, even though Bangladesh and India are supposed to be 50:50 partners. Let's talk about fact that, as per a comprehensive report by the US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), which conducts research and analyses on financial and economic issues related to energy and the environment, the plant will actually lead to higher electricity rates in Bangladesh. Published in June 2016, the report says: "The revenue requirements of the Rampal plant would require tariff levels that are 32 percent higher than the current average cost of electricity production in Bangladesh and will therefore increase electricity rates in Bangladesh. Without subsidies, the plant's generation costs are 62 percent higher than the current average cost of electricity production in Bangladesh." The true cost of the plant, it adds, is being hidden by three subsidies worth more than US $3 billion.

That the Indian government would want to pursue this case, at only a fraction of the cost and risk associated with Bangladesh, is obvious enough. IEEFA suspects "that the project is being promoted as a means to sell Indian coal to Bangladesh and as a way to skirt Indian policy against building a coal plant so near the Sundarbans, a protected forest and World Heritage Site." But we are at a complete loss to understand what possible economic benefit there could be to Bangladesh pursuing a project that has been deemed financially unviable by major international financial and research institutes. We respectfully ask the government to explain to its people the cost-benefit analysis on the basis of which it is so eagerly risking the world's largest mangrove forest, home of the Bengal Tigers, and a forest that saves us from natural disasters by providing a barrier to storms.

While we understand the need to generate power, and applaud the government for its crucial role inmitigating Bangladesh's energy crisis, we cannot comprehend why the government is remaining oblivious to what has now become a slogan for the anti-Rampal movement: "There are many alternatives to generating electricity, but no alternative to the Sundarbans". The National Committee to Protect Oil-Gas-Mineral Resources, Port and Power (NCBD), which consists of engineers, energy experts, activists and environmentalists, have proposed alternative strategies for generating electricity without jeopardising the environment and people's lives and livelihoods. Rather than engage with such groups and explore sustainable solutions for a greener Bangladesh, the government has thus far not only chosen to ignore their repeated pleas to relocate the plant, but actually responded to oppositionto the Rampal project with barricades, batons, tear shells and arbitrary arrests.

Are we to deduce, from its reaction to the mass demonstration on July 28, 2016, that violence is the only language the state understands best, or at any rate, the only language it is willing to deploy to suppress its critics? The space for democratic expression has shrunk so much so that it seems naïve to decry the violation of our constitutional rights. The arbitrary arrests of unarmed protestors, and indiscriminate beating and use of tear gas, resulting in injuries to at least 50 demonstrators, is just another "day-in-the-life-of" example in a woefully long list of attempts to suppress people's voices against harmful development projects through force, rather than productive dialogue.

It angers me, frustrates me, but mostly, scares me that the government feels that it has the power to do anything it wants – no matter the facts, no matter the consequences – and that it considers itself above and beyond all accountability to the people. As we remain distracted with our daily lives, horrific news of terror attacks and new fads on the internet, the government acts and plans in the shadows of neoliberalism, knowing fully well that the masses, at the end of the day, are too apathetic to take to the streets to demand a greener, more sustainable future, to claim from the government what is their right.

We must, for our sake, prove the 'power' wrong. We must shake off our cocoon of complicity, and ask ourselves why we cannot fight to protect our environment, the livelihood of lakhs of people and the Tigers of the Sundarbans with the same passion as we take to the streets to celebrate the Tigers' win in a cricket match; why we remain unmoved to act, content to play the part of a fool chasing after a Pokemon as the cries of the dolphins and deer of the Sundarbans fall on our deaf ears (there are headphones to block off the reality, after all). We must act, and we must act NOW, if we are to have any chance of preserving the Bangladesh that we recognise and love. The only power we need, after all, is power to the people to decide its development priorities.

The writer is a rights activist and freelance journalist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments