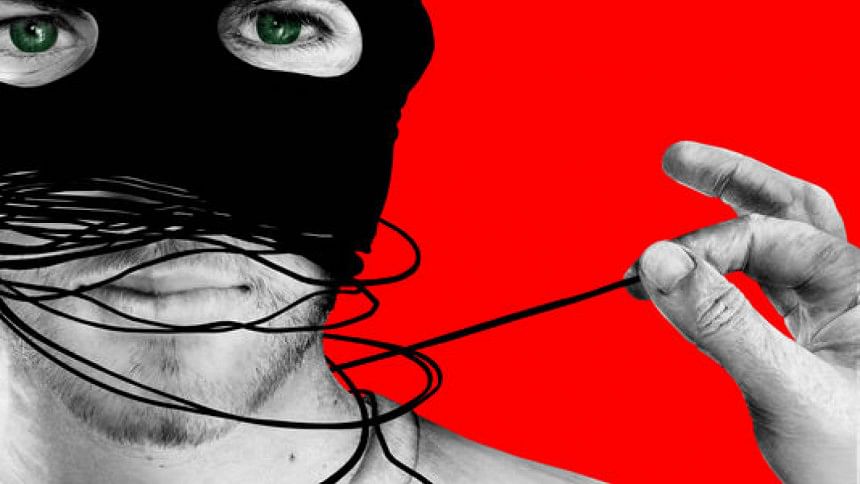

Don't blame private education for radicalisation

MANY experts and development organisations advocate greater provision of fee-charging for-profit schools in developing countries. According to The Economist, "Where governments are failing to provide youngsters with a decent education, the private sector is stepping in." [Learning Unleashed, August 1, 2015] While this view remains challenged and the United Nations has recently urged governments to monitor and regulate private education providers, for-profit schools and universities are in the spotlight in Bangladesh for a very different reason.

Following the worst terrorist attack in the country's history on July 1, 2016, government bodies and many others have been accusing English-medium private schools – schools that teach in English, offer GCSE/International Baccalaureate education,and mostly cater to well-to-do urban families – and universities of not doing enough to tackle youth radicalisation.

The government has repeatedly claimed that there is no presence of the IS in Bangladesh and the recent terrorist attacks have been carried out by local militants. After the brutal attack at Holey Artisan on July 1, 2016, the government has also stressed on the fact that many of the terrorists involved were educated in the elite schools and universities of the country. While it is true that three of the attackers had indeed studied at schools that provide Western education and guarantee English proficiency - a key marker of affluence and status in Bangladesh - young victims of this heinous crime, Abinta Kabir, Tarishi Jain and Faraaz Hossain were also graduates of an elite secondary school. This highlights a deep split in Bangladeshi society.

Soon after the attack, our Prime Minister vowed to unravel the root causes of terrorism. While government agencies are still investigating the attack, some ruling party ministers seem convinced that non-state educational institutions are responsible for the recent surge in terrorism. A junior minister was reported as claiming that some private university students are "getting involved with militancy in the private universities in the absence of progressive political activities." Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), the student wing of the ruling party, has also announced that it will form committees across all the private universities to "fight militancy".

The focus on private universities does not seem disproportionate if one considers the background of other local youths involved in terrorist activities. One of the perpetrators of the Sholakia attack on July 7, 2016, had also graduated from North South University (NSU), a leading private university of Bangladesh. Six students from the same university were arrested for the murder of blogger Ahmed Rajib Haidar in February 2013. The man accused of plotting to bomb the New York Federal Reserve Bank in 2012 was also a former NSU student.

However, the government's thinking is flawed. Exerting greater political control over the private education sector is not going to solve the problem of terrorism. The long-term neglect of education by the state in Bangladesh has created a void that private education providers have filled. Private universities have also partly grown in response to the poor performance of heavily subsidised state-run universities. Despite decades of government support, none of these universities feature in the list of the top 100 Asian universities.

A key reason for this is pro-government student politics, which condones violence, undermines scholarship, accepts corruption in teacher appointments and provides immunity against law-breaking. Many ruling party student leaders at public universities have often been in the news for acts of extortion, arson, assaults on teachers and destruction of property. This has pushed many to opt for high-fee private universities.

There are serious concerns over the quality of education in Bangladesh. Examination papers are frequently leaked. Students engage in rote learning and rely on private tuition instead of classroom lessons. Private coaching reached such endemic proportions that the government had to pass a law to ban the practice. The end outcome is a weak relationship between schooling and learning.

A recent study ("The dissonance between schooling and learning", Asadullah, M. N., and Chaudhury, N., 2015, Comparative Education Review), spoke of small gains (in terms of basic cognitive skills) from grade completion among rural children aged 10-18 years. This implies a flat schooling-learning profile and a deep crisis in the education sector of Bangladesh. In collaboration with researchers from BRAC, I found similar evidence of a low level of learning across state and non-state schools.

Fact of the matter is, a large proportion of the adolescents in rural Bangladesh is in school, but they are not learning. This is worrying because the absence of effective literacy and critical thinking ability can make youth vulnerable to radical and extremist ideologies. Not only has the government has not built enough schools or truly enhanced the quality of public universities since 1971, budgetary spending on education has rarely exceeded 2 percent of GDP.

If the government is serious about tackling terrorism, politicisation and increased surveillance in educational institutions will not be enough. Despite many limitations, private schools and universities have for decades served as a complement to the state's educational initiatives. They should not be singled out as a security threat.

Stereotyping non-state educational institutions will only create more divisions among Bangladeshi citizens, making it harder to build a political consensus to fight radicalisation. If anything, these institutions can be an effective force against insurgency by improving national literacy rates.

Instead of blaming students of English-medium schools, the government should focus on enhancing the quality of government schools, which are increasingly becoming weak substitutes for non-state schools.

Extremist outfits are more likely to prosper in an environment without accountability. Lack of good governance, a broken public education system and democratic deficit, and not private schools or the absence of party politics in private university campuses, create a hotbed for terrorism.

The author is Professor of Development Economics and Deputy Director of the Centre for Poverty and Development Studies (CPDS) at the University of Malaya. Email: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments