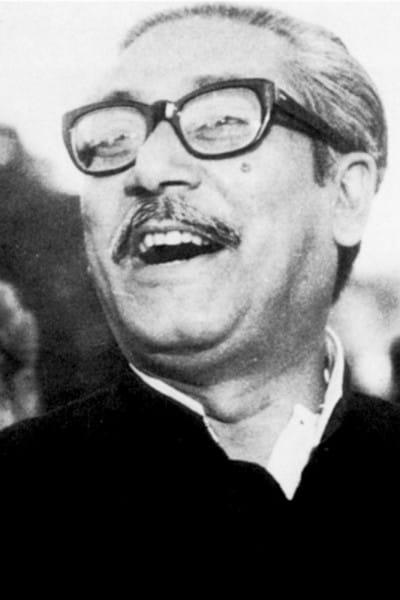

The Towering Courage of Bangabandhu

For the uninformed multitudes, remembering Bangabandhu on August 15 is perhaps a ritualistic observance when the mind does not delve deep to grasp the historical significance of the tragedy. The ignorant and the deviants in our midst cannot be blamed for their short-sightedness because the distortions of our political history were done at the behest of pitiable villains occupying the pulpit of power. The crude efforts to denigrate and sideline Bangabandhu, the architect of our freedom and catapulting the minor players onto the centre stage would remain a shameful part of our existence.

The assassins of 1975 were able to physically do away with Bangabandhu but did not realise that erasing him from the hearts and minds of Bengalis was practically impossible and morally indefensible. The immutable fact of history all Bangladeshis and the rest of the world ought to know is that the towering courage of this Bengali was instrumental in the creation of a sovereign nation. So fearless and altruistic was this man that he spent nearly two-thirds of his youth in prison for the emancipation of his people.

Imagine the 1960s when Bengalis of erstwhile East Pakistan were subjected to the most humiliating treatment. It would be no exaggeration to state that they were experiencing the tribulations of a colonised people. In an atmosphere of all-pervasive fear and subjugation, it was Bangabandhu who confronted the mighty Field Marshal Ayub Khan and showed the guts to forcefully advocate the rights of fellow Bengalis. During the trial of the so-called Agartala Conspiracy Case in Dhaka Cantonment, Bangabandhu took to task the rogue Pakistani army personnel and cautioned them to behave. He did not agree to participate in the Round Table Conference as a prisoner. The 1960s were, in fact, a time when all Bengalis could justifiably take pride in their courageous manner that drew sustenance from Bangabandhu's defiant disposition.

Bangabandhu was a real epitome of courage, both in the physical and moral sense. The historic Six Point Programme, an explicit embodiment of Bengali nationalism was unfurled at Lahore, the heart of Punjab by Bangabandhu. In Lahore, the bastion of arrogant Punjabi power, Bangabandhu displayed admirable physical and moral courage during the course of a public meeting in 1970 that he was addressing.

It so happened that his speech was being purposely interrupted by some Muslim League-Jamaat hirelings. When these elements did not stop even after being cautioned, Bangabandhu shouted at them, asserting that he had not come to Lahore to seek votes as he had plenty of them in his place, and that they either listen to him or disappear from the meeting area. No Bengali had ever publicly ventured to rebuke the power-obsessed high nosed Punjabis in such a raw manner.

When Bangabandhu, the poet of politics spoke, it had an electrifying effect on the Bengalis whose spirit soared immeasurably in heightened expectations. Their support for their leader was total as evidenced in the historic landslide electoral victory of the nationalist causes in 1970. When the time came for tough talks across the table, Bangabandhu did not wilt. In fact, the cabal of Pakistani army generals that accompanied General Yahya Khan for the meeting in March 1971 were awed and surprised by the gutsy presentation and forceful manner of Bangabandhu.

It is an irony of the sub-continental political progression that while the prescribed text books of social science and literature were supposed to turn Indian gentlemen taking to western education into rebels, in reality, scores of them joined the imperial service to obediently serve their colonial masters. Similarly, a large part of the so-called constitutional methods oriented politicians of undivided India were more occupied with their personal and material safety and hardly posed a threat to the British might.

The post-partition scenario in Pakistan did not witness much of a change. The military-civil bureaucracy conspired with the business oligarchy and the landed gentry to protect their vested interests. People's emancipation did not figure seriously in the politician's scheme of things. It was in these circumstances that Bangabandhu could galvanise a somnolent people to unprecedented political activism for achieving real freedom.

Bangabandhu was gifted with extraordinary organisational acumen and had the inkling of the brutality of the Pakistani military junta. Accordingly, he exhorted the people for an imminent armed struggle. His historic 7th March speech bears an eloquent testimony to that. Precariously positioned as he was in the extremely demanding tumultuous days of March 1971, Bangabandhu as a constitutional politician acted with supreme forbearance.

Bangabandhu could never be cowered into submission. The trappings of power did not allure him and he remained a solid rock in the shifting sands. It is time once again to gratefully remember and pay homage to the great patriarch.

The writer is a columnist of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments