Making best use of old Central Jail area

The recent controversy with the land use of the would-be-abandoned central jail area shows how short our memory is collectively. It has been almost 100 years since the issue was raised and resolved in 1917 in favour of creating an urban park on the freed land. The main advocator was Sir Patrick Geddes, widely recognised as the father of modern town planning. In fact, all other subsequent plans for the city of Dhaka in 1958, 1981 and 1997, have suggested doing the same. The last of these, the Dhaka Structure Plan, has just quietly expired its time period (1995-2015); however, the much-hyped DAP (Detail Area Plan) based on it is valid till there is a new Plan. Hence it is the only justified and legal thing to consult the DAP as to the use of this valuable land.

In this regard, I remember the workshop (of experts) organised by RAJUK on draft DAP in September 2007. Though I represented the Institute of Architects Bangladesh (IAB) in that meeting, I was keener to voice a citizen's conscience. But we were dismayed to see that the consultant had proposed developing commercial uses on the land to be vacated by the relocation of the central jail, after mentioning that it has no historic value. I opposed this instantly, and suggested keeping the land as a much-needed open area for the Dhakaites, which I presume was later adopted in the revised final version. I had left the country after a while, and currently have no access to a copy of the DAP; but it will be worth checking.

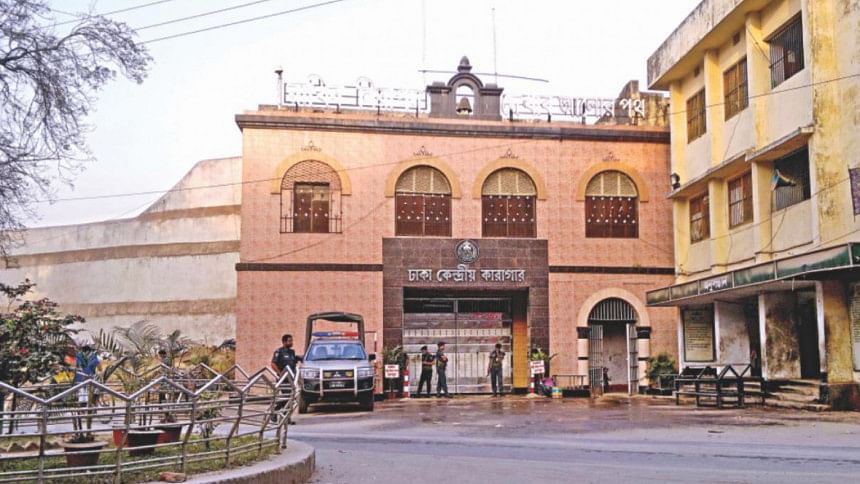

The Central Jail, originally a fort encircled by mud walls, was erected by Sher Sah Suri. At that time, it was on the outskirt of the city confined by the river (Buriganga) and Dholai Khal. In 1602, Man Singh set up his garrison there; his entourage settled in between the fort and the Dhakeswari Temple, in an area that was therefore named as 'Urdibazaar'. When Islam Khan Chisti's move towards Dhaka was stalled in Shahjadpur due to rain and flood, he sent an advance party to Dhaka to repair the old fort in order to make it suitable for his court and residence. It is only suffice to say that the central jail area is no less historically important.

It surprises me that we are forgetting the government held design competition as to the most befitting use of this land in the late 1980s. It was won by a group of architects, who incidentally were my classmates. One of them years earlier had undertaken this very project as his final thesis, and proposed a low-rise mixed use in an intimate scale that we usually associate with old Dhaka. At about the same time, another architecture student took up the same exercise as his final project. And ever since, the reuse proposal for the central jail area became a popular architectural exercise in different architecture schools of the country.

Another architect, who was then my graduate student, came up with a daring and exciting proposal with symbolic content; yet it was surrealistically simple. He adopted two bold premises and the postulations thereof, connecting old Dhaka with the new with an axis cutting through the land. The axis originated at Swari Ghat, connecting the Chawk (originally an open plaza surrounded by important structures like the fort and mosque) through the Bara Katra. On the other tip of it was the point where the Swadhinota Stambha (which now proudly stands in Suhrawardy Udyan), via the Kendriyo Shahid Minar. This line thus represented the history of the city starting from when it became for the first time a capital. In fact, Islam Khan in 1610 landed somewhere near the Ghat (Pakurtuli in the Babubazaar area), paraded by the outer periphery of the city, and reached the old Afghani Fort.

This line will cut 85 percent of the land on the west, which he proposed to keep green, from the more historical east part with Purba Darwaza (East Gate) as a formal entry. This part had a mix of small-scale civic-cultural uses. The statement the graduating student made was bold and definite, and unseen for years in a project at this level in any architecture school in Bangladesh. It was highly applauded, and was exhibited at the Shilpakala Academy. But all such proposals, many of which are valuable and posses a high level of practicality, in terms of directing towards enhancing the amenities and livability of the city, are never taken up to be implemented.

Of course, the context may have changed over the years and the use of this core city land needs to be carefully re-examined and a proposal be made and executed, taking into cognizance the history of the land, morphology of the surrounding area, and the needs of Dhakaites. More importantly, the site provides an opportunity of a lifetime to do something for the city that its citizens can be proud of (we have somewhat wasted another such opportunity with part of the old airport unless that is made publicly more accessible). In his article titled "Can city design prevent terrorist attacks", published on August 27, Adnan Morshed had aptly stated:

"The city's young needs playfields to exhaust their energy. How serious are urban administrators in Bangladesh about preserving neighbourhood playgrounds as a way to keep the youth engaged with city life and away from the dark underworld of nefarious indoctrination? About 52 out of Dhaka's 90 wards (60 percent of the metropolitan area) have no access to parks or playgrounds; only 36 have some open space ranging between 0.01-0.21 acre per 1,000 population. Have we thought about how neighbourhood playfields would help create more Shakib al-Hasans and less Nibrases?

(. . .) The demand for urban land is skyrocketing, leading to misguided policies of gentrification and a mastani culture of land-grabbing. Experts recommend that a liveable city should have a minimum of 25 percent of its area as open space. Dhaka's open space is only about 14.5 percent and rapidly shrinking. Research has shown that without adequate public plazas—essential for a city's democratic practices, recreation, and community-building—the antisocial instincts of city dwellers balloon."

Now we have 25 schools of architecture with several thousand students and about 3,000 professional architects practicing in Bangladesh. Let's organise a two or three phase open urban design idea competition for both students (can be from architecture, planning, history, or any background from any of the nearly 100 universities) and professionals (could include architects, planners, engineers) or groups thereof. The first phase can be a one-day design charrette; a brief can be developed from ideas of this phase. But such a brief must include a symbolic representation, iconic structures, an open area, and mixture of small scale cultural uses.

Such participatory design approach will indeed contribute to the sustainability of whatever use that would be proposed and built in the area as a result, and will remain as a milestone in the city's history.

The writer is Professor and Dean of Engineering and Design, Kingdom University, Bahrain.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments