A Dramatic Fall

Tania, Tania, Tania!" a ponytailed musician-type claps furiously. He is apologising to his girlfriend. His face looks as though it were made of wax; so, his mouth moves when he speaks but the rest stays absolutely still. He drones on about having sent multiple, multimedia apologies. The dialogues are artificial and delivery, appalling. No wonder she is oblivious to his pleas. By the time the 22-minute script recital nears an end, the girlfriend is unsurprisingly leaving him to go and shack up with a famous musician. It feels like welcome relief.

Let's consider another example: a broken-up couple spends 22 minutes spying on each others' love interests and sabotaging any budding relationship. Nothing but 'love' and 'relationships' exist in the one-dimensional protagonists' lives. Neither the woman nor the man has any defining struggles or more importantly, a raison d'etre. None of the sabotaging interventions contained a morsel of drama, suspense or wit. Not one of the new love interests are developed as characters, not even quirky ones. Monolithic, superficial and uninspired characters, watery and callous dialogues and a high-pitched background theme struggle to hold the story together. It all seems like sugar-coating for a deluge of advertising, which incidentally have better production value.

The examples are from the previous Eid, and if television programming during Eid festivals are any indication, the glory days of Bangla natok/drama are long gone. A 'drama' is defined here as half an hour of fictional television programming, also known as a natok or a telefilm. It can include both standalone stories and serials.

There was a time when stellar writers and visionary directors were experimenting with magic realism and satire, dealing with inner demons and writing up characters whose on-screen deaths could inspire real-life street protests. The Bangla natok was a genre bubbling with creativity and innovation. Shokal Shondha, Dhakai Thaki, Ei Shob Din Ratri, Shangshaptak, Bohubrihi, Auyomoy, Kothao Keu Nei – each of these was a window into people's souls, a mirroring of the lives and spaces that they inhabited. Characters' struggles were real and took place within real sociopolitical tensions.

It is not possible to reference the many brilliant dramas that aired through the 1980s to the mid-2000s. But a particularly striking story by Humayun Ahmed comes to mind: audiences saw a professional eater (khadok) summoned by a landlord, to eat an entire cow and thus amuse the crowd. The khadok proceeds as planned, but is soon thwarted by the enormity of the task ahead. He gasps with every swallow. His impoverished family begs him not to eat anymore. But he soldiers on, perhaps for the prize; perhaps as a selfish act; perhaps to somehow eat on behalf of his family. Perhaps pride is more important than the tragedy of a father gorging on a feast in front of hungry children. Regardless, the mob is enchanted and the landlord, amused. Presumably developed as a short story, the story of the Khadok explores feudalism, mob psychology, family ties and host of other social aspects. It leads audiences to question the kind of society where competitive eating is a profession and feudal lords make a display of power through such excesses. In short, it was thought provoking.

It has all been downhill from there. Today, dramas have been reduced to formulaic structures, unimaginative storytelling, drivel for dialogues, crass antics and cheap laughs. The emotional range is limited by unrequited love, infidelity and family feuds. Sub-currents in the genre include the use of exaggerated local dialects/accents and overrepresentation of urban characters. Casting homely middle-aged men against young, glamorous female leads is becoming increasingly common too. The utter stagnation of imagination is hardly compensated for by high-definition videography and slick camera movements.

In present day dramas, quirky characters and over-the-top accessories like tacky sunglasses and catchphrases are used often and to little effect. Scenes seem designed to lead from one commercial break, to the next. Combined with recaps and repeated shots, the space for laying plot foundations and working up climaxes have been severely restricted.

Casting has suffered too. Almost all dramas these days cast commercial models or social media celebrities, leading to the inevitability of all miracles and tragedies of life being met with looks of smouldering glamour. A vast nondescript swarm of artistes have replaced a pantheon of small screen fan favourites. Though some male leads from the early 2000s still cling on to their roles as young(er) heroes, corresponding ladies (from Shuborna Mostafa to Bipasha Hayat) have nearly disappeared from the small screen.

In their place have risen a generation of performers with little emotional latitude, whose only talent seems to be rapid-fire delivery of improvised dialogues. Maybe this is why directors feel compelled to carve scenes into bite-sized chunks that semi-professional actors can deliver and inattentive audience can swallow. Thus opportunities to showcase the beauty of language, prose, poetry and philosophical monologues have all but waned.

How did the Bangla natok get here? The new generation of writers and directors has grown up with easier access to the treasure trove of global visual arts. They have the increasing option of delving into the global art and archive of storytelling, thanks to video streaming, downloads, DTH services etc. There should be no lack of reference material or inspiration.

I will argue that there are reasons why the contemporary natok is typically sentimental drivel combined with impatient commercial breaks, disguised as entertainment; why nearly all TV dramas feel like extended Airtel commercials. That reason is 'economics'.

TV dramas have gone from being an art to an industry. In the present arrangement, writers and directors are given a 22-minute slot to fill. Payments are made based on revenues from channels. Therefore, it is typically more profitable to produce two subpar shows than a good one. Given the short shelf-life of dramas and falling viewership ratings, advertisers find them a little less attractive as sponsorship opportunities. The solution? Cut costs.

Focus on cost minimisation too means compromising on creativity and casting. Suddenly, using living rooms and overused sets like Beauty Boarding/Hotapara are preferable to investing in sets that complement the plot. Despite falling quality, there are enough television channels in Bangladesh to absorb the quantity of dramas being produced – and this constitutes the last nail in the coffin: a lack of healthy competition. Writers/directors too seem resigned to a fate of captive audiences, who have no better programming options.

The traditional drama is facing competition from new programming formats. One such example is the 'reality show' – which has captured popular imagination with a somewhat-unsavoury mix of challenge, naked ambition, loyalty, treachery and humiliation. Cable TV and torrents bring in videos from the entire planet. Social media contents (e.g. YouTube skits) may soon pose a challenge to the format too. The time is not far when Bangla dramas will have to evolve or become extinct.

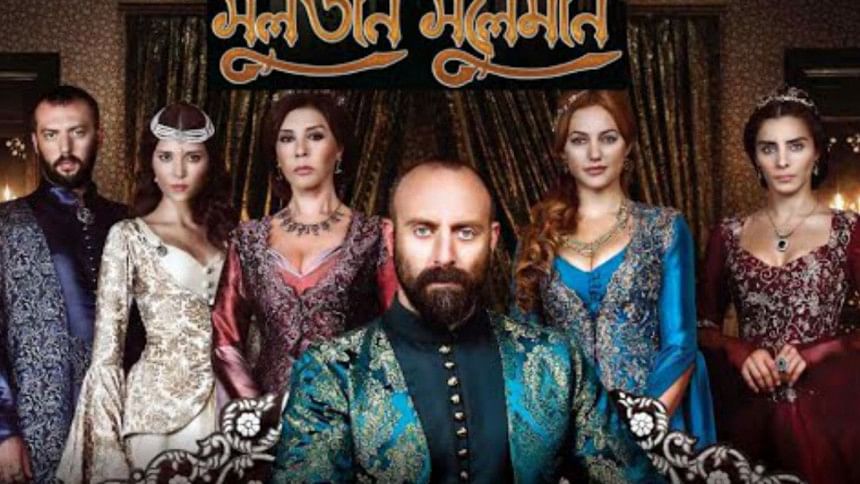

Deep inside rural Bangladesh, housewives have turned to Indian programming, mostly soaps and reality shows. Not a month ago, the popular show Kironmala led to an actual brawl in Habiganj that left over 100 injured. Not that it is any indication of the show's merit, but the incident does hint at a certain degree of social significance. This changing viewership dynamics will obviously effect a national change. To illustrate, let's try a quiz: which do you think is the most-watched programme on Bangladeshi television channels? Think hard before you answer. Well, it is Sultan Suleiman, a Bangla-dubbed Turkish historical fiction about the conquests, romance and palace politics of the Ottoman Sultan.

Shows finding currency with Bangladeshi audiences seem to offer articulations of traditional values, modern struggles and social change. Like Sultan Suleiman, the typical Hindi serial too is a cauldron of melodrama, spiced with love, envy, betrayal and family bond. Yet, they don't fail to comment on the importance of traditional values: foregoing own convenience in the service of others, caring for ageing parents or sharing among siblings. These reflect real socioeconomic issues and real gender mainstreaming challenges – and thus make the shows relevant to the audience. Yet a cursory look at the 300-odd package dramas produced for Eid-ul Fitr this year reveals that none of them thought to include the spirit of abstinence or moderation in the scripts.

Every form of art is a reflection of life and society. Such reflection is as much an artistic expression as it is a social necessity. When an art form loses that connection, new forms and genres must rise in its place. And from that perspective, the genre of Bangla dramas faces not only a commercial, but an existential threat.

The writer is a strategy and communications consultant.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments