What's in a frame?

It was always destined to become iconic: an image of blood-red streams flowing through a cityscape. The city was Dhaka and the liquid flowing through its thoroughfares sure looked like blood. Plug in the words 'Qurbani Eid' – and what becomes evident to unfamiliar readers is ritualised sacrifice of animals in an unimaginable scale.

So, while Bangladeshi media bemoaned the waterlogging and lack of drainage, especially around the Shantinagar area, many international outlets concentrated on the portentous imagery. And let's be fair: without context, the photos are quite striking and open to wild interpretations. In fact, the images are more striking than the actual story. Add a little sensationalist editorialising, and we have a spectacle.

"Rivers of Blood," international media outlets christened the phenomenon. And what a story it made! So primitive, so Biblical, so photogenic! There was definitely something in that phrase that harkened one back to Biblical times. Magical, mythical times when the Nile could turn red, seas could part and divine signs were common.

International readers had little way – looking at the 'rivers of blood' photos – of concluding that the phenomenon was localised, that the neighbourhood had struggled with waterlogging for decades and that the 'rivers' would be drained out and the streets cleaned within 24 hours. They only saw the prophetic photos and those ominous words 'rivers of blood'.

Some of the ensuing comments were harsh and viewed the incident solely through the lens of faith. The religion is condemned as barbaric, uncivilised and backward. Animal sacrifice is framed as a precursor to violent extremism. One commenter blamed the Pope for 'bowing to the enemies'. Others zeroed in on Bangladesh – in an exercise in Orientalism – theorising that her people lived in filth or advocating that development aid to such countries be stopped.

Bangladeshi conversations, as judged through social media reactions, have been varied. Waste disposal and hygiene formed the core. Belief, morality and kindness formed the pith. Commentators have taken to questioning and defending the raison d'etre and manner of animal sacrifice. Resistance has come in the form of accusations of Islamophobia and selective targeting of Qurbani Eid. Some have felt an unfortunate dysfunction had been turned into a chance to shame a developing and/or Muslim (majority) country. There are now doctored photos with rainbow colored rivers through Dhaka streets, insinuating that the original photos too were manipulated.

Why do certain images create such ripples? Well, striking photographs have high potential to become a vessel for meaning / ideology and for becoming embedded in the viewers' psyche. Gandhi and his spinning wheel (Margaret Bourke-White), child protestor from 1969 Revolt (Rashid Talukdar), grenade throwing boy,1971 (Naib Uddin Ahmed), last embrace at Rana Plaza (Taslima Akhtar) – are just some iconic photographs that convey more than what they contain.

The amount of interest, reactions and arguments generated by the 'river of blood' photos make them symbolic too. That is to say, they possess the capacity to embody ideas and events. What the images mean depends on what readers (want to) believe: Dhaka has a serious waterlogging problem? Certain quarters are out to undermine the institution of animal sacrifice? Muslims are a backward group? Journalists unnecessarily sensationalise waste stories for higher readership? Each of those points-of-view can be raised and advanced with the help of the 'river of blood' photos.

Of course, the use of images, natural, staged or manipulated, in advancing political motives is not new, and happens in every country. Photojournalist Michael Kamber, on his website Altered Images (alteredimagesbdc.org/), has been exposing edited and doctored photos, many of them iconic and moving. An innocuous example is a photo of President Obama, distracted, dejected and resigned at the beach. In the distance, oil derricks and tankers are seen. The photo is on the cover of The Economist, and the story is about a BP oil spill. It is soon revealed that two colleagues talking to the president had been digitally cropped out or removed – leaving Obama to radiate an air of isolation, burden of rule and exhaustion. A deputy editor later defended this manipulation, because she wanted to "focus on Obama."

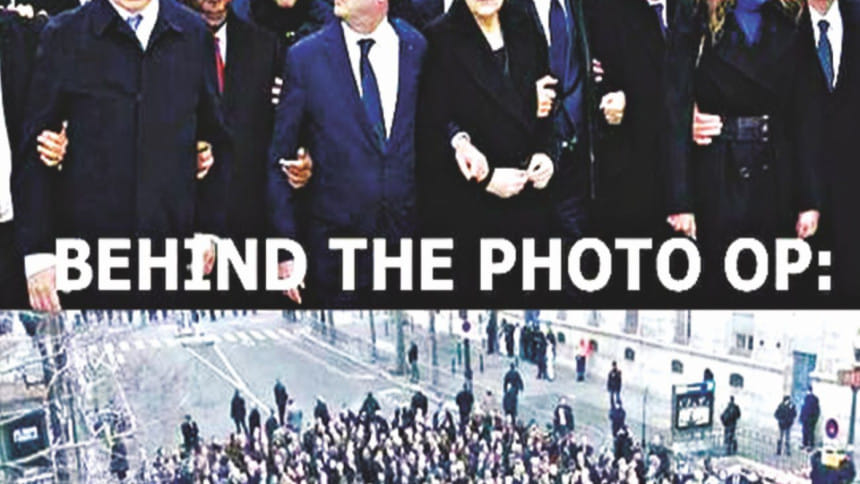

In January 2015, world leaders gathered in France to lead the rally against terrorism and honour the dead in the Charlie Hebdo massacre. There were some four million protestors and at the forefront, the news showed, were leaders from Asia, Europe and Africa. It was on its way to become an iconic image in world politics, when a wider shot revealed that the photograph was staged on an empty street, away from the actual rally and under tight security blanket. The impression of unity and courage in the face of attack was instantly shattered and the photo-op started garnering widespread ridicule.

A clear testament to the power of photography in modern, public discourse is a recent, unfortunate decision by the young billionaire prodigy Mark Zuckerberg and his media site, Facebook. Zuckerberg was accused of removing a photo posted by a Norwegian author. It was the Pullitzer winning 'Napalm girl' photo by Nick Ut, which shows children, including a naked, young girl, running away from Napalm bombs. The photo is a veritable testament to American atrocities during the Vietnam War.

Facebook, on the other hand, argued that it did not allow child nudity on its site and demanded that the photo be taken down, or the girl's genitals and breasts pixelated. This drew allegations of censoring criticism (of the USA) and misuse of power by the 'most powerful editor'. After a high-profile open letter addressed to Mark Zuckerberg, the photograph was restored to its place.

More and more striking photos are characterising and describing our world. At the same time, more and more quarters are vying for control over interpretations and meanings. You see, the power of photographic narratives is also their greatest weakness: they represent a partial perspective at a specific point in time. Photographic context and degree of essentialisation are treated as artistic or journalistic choice, and not a fundamental, discursive act. So, especially in the case of publicly circulated and/or shared photos, meaning is often interpreted or imposed by different narrators. This, and ease of digital manipulation, makes photographs a potent but vulnerable source of public discourse.

The writer is a strategy and communications consultant.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments