Must not be the legacy we leave behind

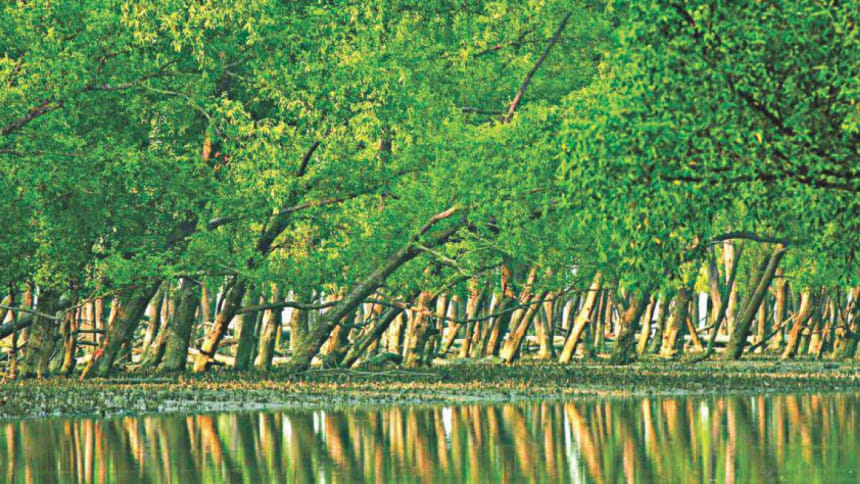

That the Sundarbans, the unique world heritage site and a lifesaver for the coastal people, is in grave danger, with or without the planned Rampal coal-based power plant is not in dispute.

Since the 1940s, the mangrove forest area has shrunk by three quarters from around 40,000 sq.kms to 10,000 sq.kms – with 6,000 sq.kms within Bangladesh. The culprits are many – from silting and rise of water salinity including the diminished flow of rivers caused by India's Farakka dam, encroachment of the forest by people seeking livelihood; poaching of animals and trees; navigation of freight carrying ships through forest channels; and inept enforcement of forest protection laws.

Can the Sundarbans survive another major onslaught in the form of the power plant – with the pollution of air and water, disposal of wastes, passage of coal barges, erosion of the river banks, movement of machines and material for construction and maintenance of the huge infrastructure; as well as the collateral influx of people, businesses, industries and traffic within 14 km of the Sundarbans boundary?

The arguments for and against the power plant in close proximity of the Sundarbans parallel the debate between climate change deniers, such as Donald Trump, who reportedly said it is a Chinese hoax, and others including the mainstream scientific community who sees it as a looming disaster for humanity and the planet. The vast majority of people in the world, even if they are not sure of the worst case scenario, would like to see major global and national action to limit the damages, because the risk of not acting is too great and irreversible.

By way of full disclosure, I should say that I am not an expert on power generation or environment. But as a concerned citizen, who tries to make informed judgement about matters of paramount public interest, I am not convinced by the case for the coal power plant on the proposed site.

There are too many weaknesses and loopholes in due diligence about assessing environmental impact; preventing and mitigating the predicted damages to air, water, land and flora and fauna; the approval mechanism that seems to be designed to go ahead at any cost; and the absolute need for locating the plant on the designated site.

Promises about super-technology, super-regulations, and super-monitoring preventing the damages are mere promises that cannot be relied upon. Just look at the record of applying and enforcing all the laws and regulations in the book on environmental and other matters.

On the other hand, the independent scientific community within the country and outside, including UNESCO and IUCN, has opposed building the plant on the proposed site. They have cited the risks and likely damages, and have cast doubt on the efficacy of the technological solutions mentioned, some as afterthought since the dangers were noted by the dissenters.

The dissenters have proposed alternatives, such as shifting the plant farther away and/or use of liquefied gas instead of coal as the raw material. Convincing and serious responses have not been provided by the government about why the suggested alternatives could not be considered.

What is worrisome is the position – political and administrative – that the plant as designed would be built no matter what and that those who oppose it are ignorant, misguided or, worse, against development of Bangladesh. The political and technical people at high level, who advise the prime minister, it appears, have failed to be sufficiently objective, professional, and mindful of the larger and longer term public interest.

The average life of a coal-based power plant is understood to be no more than 40 years and it would meet only a small fraction of the power need of the country during this period. The likely damage done and harm caused to the Sunderbans would be forever. The assault on its fragile and highly vulnerable ecology may be the last straw that breaks the camel's back -- leading to virtual decimation of what is left of the Sunderbans.

I would like to believe this is not the legacy we would like to leave for posterity.

The writer is professor emeritus at BRAC University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments