Dissent and the price of freedom

"The silencing of dissent, and the generating of fear in the minds of people violate the demands of personal liberty, but also make it very much harder to have a dialogue-based democratic society."

THUS said the Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen, speaking of whom, we never forget to mention that he was born in Bangladesh, at the annual Rajendra Mathur Memorial Lecture organised by the Editors Guild of India in 2016. Strong words reminding us of our right and the importance of dissent in a democracy. And we need to be reminded, time and again, because in our collective silence, our looking the other way, our self-delusions and our collusions for petty gains, we forget that it is imperative to speak up, to take a stand, to take the opposite stance if necessary when our morality is shaken and rights of people are trampled upon by the powers that be.

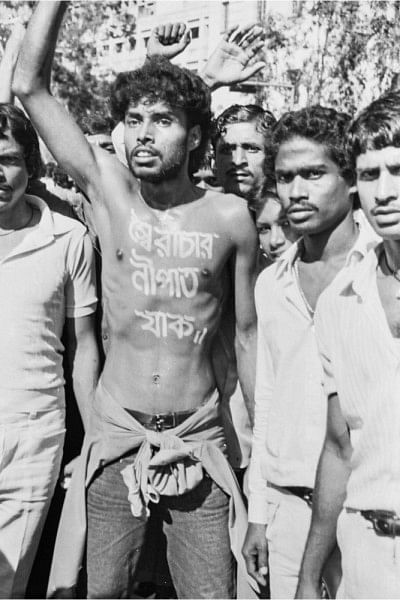

In 1987, stronger words reminded the nation of what was at stake. "Sairachar nipat jak; Ganatantra mukti pak" (Down with autocracy; Let there be democracy). With these words painted on his chest and back, Noor Hossain took a stand against the autocracy of Lieutenant General Hussain Muhammad Ershad as part of the the Dhaka Siege on November 10. The rally turned bloody, and Noor Hossain was killed under riot conditions, reportedly from police firing.

He wasn't the only martyr in the movement for democracy that was waged from 1982 to 1990. In 1983, during a protest rally by students against the education policy of Dr. Majid Khan, eight people were killed by the police. In the same rally that Noor Hossain was a part of died Nurul Huda Babul and Aminul Huda Tito (Shoiro Shashoner Noy Bocchor, Major Rafiqul Islam). There have undoubtedly been many more, and we forget their names. But Noor Hossain, a barely educated common Bangladeshi, who had only studied till Grade eight, became a symbol of resistance to authoritarian power then, as he should be now.

In March 1982, Lieutenant General Hussain Muhammad Ershad proclaimed the military rule ordinance. It read:

"… with the help and mercy of Almighty Allah and blessings of our great patriotic people, [I] do hereby take over and assume all and full powers of the Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh… as Chief Martial Law Administrator"

I read this today, almost three decades later, and I cringe at the words. The irony of martial law and a military dictator in a 'People's Republic.' With such self-assuredness, the decree promises to right all wrongs. A messiah like figure promising salvation from the "state of extreme frustration, despair and uncertainty", for the "greater national interest" and "national security." Almost in passing, the decree adds that his orders will be the "supreme law of the country and if any other law is inconsistent with them that other law shall to the extent of inconsistency be void."

It would be eight more years till Bangladesh would gain back any semblance of democracy. It would take Noor Hossain's courageous stance, mass movements, cross-partisan alliances, and a united stance in the name of democracy to see the day in 1990 when Ershad would yield. And yet, the parties which came together against Ershad then, subsequently forgot what they fought for. The words of Noor Hossain's mother in an interview, painfully, ring true: ''I still don't see anything for which my son died." (New Age, November 10, 2005)

It might be naïve of me to ask what makes those in power fear the voice of the people. And what, especially in our subcontinent, brings on repressions - even by democratically elected governments - on people's protests. After all, I might foolishly add, a democracy is supposed to be the embodiment of a people's decision. So, why are those who do not agree with power harassed, branded seditious, called unpatriotic, and silenced?

Why is it when a citizen of the country who does not agree with the government's decision to build a coal-fired power plant near a Unesco World Heritage Site, they are automatically relegated to being 'anti-national' or 'unpatriotic'? Is silencing of voices somewhat more legal when done through legislation? If not, then are laws like the The Foreign Donations (Voluntary Activities) Regulation Bill 2016, which makes it an offence for foreign-funded NGOs to make "inimical" and "derogatory" remarks against the Constitution and constitutional bodies, any more democratic than what we fought against? Or the Digital Security Act, 2016, which if enacted, would silence dissent online, and promote self-censorship in the name of that vile term 'national security'?

The Indian historian Romila Thapar, in an interview with Caravan Magazine in the wake of the student protests in Jawaharlal Nehru University against the death sentence of Afzal Guru and the subsequent branding of them as 'seditious', pointed towards the colonial roots of sedition in the subcontinent:

"Sedition was introduced at a time when India was a colony and was governed by an alien power. Now we are an independent nation with an elected government. It's a democratic Parliament. So, the situation is entirely different. Is it, then, legitimate to have sedition as a punishable offence?" We wonder.

On this day, Noor Hossain's dissent was silenced near Zero Point, when he took a stance against authoritarianism. Yet, his gesture, made immortal, was seen again during the call for punishment of war criminals during the Shahbagh protests. And the man against whose rule he protested, has apologised, unapologetically with the caveat: that Hossain was merely used as a symbol against his government. But what of those who were beside Hossain that day? Have they done enough to make a reality the democracy for which Noor Hossain died, where criticism is not sedition and dissent is not anti-state? We commemorate Noor Hossain Day with pride and reverence, but in doing so, we must remain vigilant about morphing the ideals of his dissent into mere hollow words. As the Nobel Laureate who was born in Manikganj, Bangladesh, reminds us:

"Vigilance has been long recognised to be the price of freedom."

The writer is a member of the Editorial Team, The Daily Star.

PHOTO CREDIT: Dinu Alam, CC BY-SA 3.0, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29684819

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments