A woman's right to a life of dignity

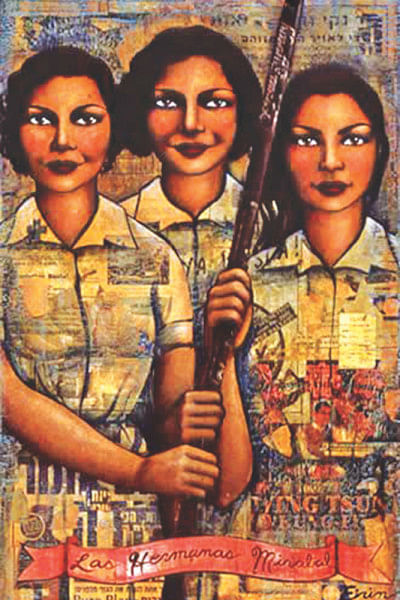

In 1960, three sisters, now famously known as the Mirabal sisters, were brutally assassinated on November 25 in Dominican Republic for their role in opposing the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo. The sisters were part of the 14th of June Movement, a leftist clandestine group opposed to the Trujillo regime, and remain, to this day, symbols of feminist resistance to unjust rule, greed, corruption, and suppression of freedom of speech. Thirty-nine years later, in 1999, the United Nations General Assembly designated November 25 in honour of the Mirabal sisters as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women to strengthen global commitment, raise public awareness and join hands in fighting this menace that breeds fear and despair in the lives of girls and women.

Every year, women's rights activists, NGOs and international bodies commemorate the day to, in part, feed into the public consciousness the urgency to collectively take action to eliminate violence against women and girls around the world. However, the conversation on this pandemic must continue even in the absence of such 'special days', and societies must move beyond the point of mere observation of international days in the form of conferences and dialogues where 'experts' cite a few statistics and a handful of recommendations. Despite the strides women have made in every sphere of life, gender-based violence is rampant and is one of the greatest obstacles in the path towards advancing women's rights and achieving equality.

The underlying causes of this are complex and numerous; customs, cultural norms and tradition, and gender stereotypes in a patriarchal society of political and economic structures largely skewed in favour of men contribute to the abuse and neglect of girls and women who are exploited in dehumanising ways, both physically and emotionally, in every corner of the world, whether it's a conflict zone in Syria, an affluent suburb in the United States, or a village in Pakistan.

At home in Bangladesh, the story is no different. Despite having a woman as the head of state, a woman as the leader of the opposition political party, a woman speaker in the national Parliament, and one of the world's first all-female UN peacekeeping units, Bangladesh is far from eliminating the social malaise that is violence against girls and women. This year alone, at least 548 women have been raped resulting in 29 deaths (from January to October) in Bangladesh, according to Ain o Salish Kendra. When 19-year-old Tonu's lifeless body was found near a culvert in Comilla's Cantonment area after she was raped and murdered earlier this year, we saw massive protests and outcry on social media. Eight months on, however, her bereaved family is yet to see the light of justice. Then there was 14-year-old Risha who was stabbed to death three months ago by a stalker who was recently taken into custody by RAB. There is the college student Khadiza who was attacked with a machete last month, also by a stalker (a BCL leader who is set to stand for trial in the coming days). After fighting for her life in the hospital for weeks and undergoing surgeries on her brain and limbs, Khadiza has fortunately recovered although she can barely move her left hand and leg. These are only few of the countless acts of violence that girls and women in the country are regularly subjected to, a minority of which are either reported or make it to the news.

Although we have laws in place, such as the Cruelty to Women Ordinance (1983) and the Prevention of Repression against Women and Children Act (2000), to bring perpetrators of such crimes to justice, it is the norm rather than the exception for sex offenders and murderers to go unpunished due to the improper implementation of legal mechanisms among other factors. It is not surprising that legislation alone isn't an effective deterrent when there is little weight placed on gender-based violence and its far-reaching implications in the mainstream political discourse which is often focused on issues perceived to be the sole contributors to the country's economic development (i.e. energy, transport, etc).

The above assumption, however, could not be more flawed. An understated fact is that besides psychosocial costs, immense economic costs are also embedded within acts of violence against women. Domestic violence, for instance, can incur costs of medical treatment, court proceedings, social protection (shelters, safe-houses, child protection), and loss of wages for those affected. According to a cost analysis study conducted by CARE Bangladesh, the leading cause of domestic violence in the country is dowry followed by strained relationships with in-laws and other reasons such as poor housekeeping and unsatisfactory cooking. The study found that survivors and their families paid on average Tk. 11,900 in direct costs compared to Tk. 10,400 paid by perpetrators and their families. Such expenses not only hemorrhage resources that violence against women continues to exact but also have consequences for development in the long-run.

During the ongoing 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence Campaign (November 25 to December 10), we must promote the idea that "the best way to end violence against women is to prevent it from happening in the first place." First and foremost, this entails working with young girls and boys from an early age in developing respectful relationships with the opposite sex, which minimises their likelihood of internalising sexist social norms and practices that normalise violence against women. Given that such suggestions are often overlooked at the policymaking level, the benefits of inculcating egalitarian values at the early stages of child development and learning merit special attention. Aside from addressing the obvious factors such as lack of access to justice and security, policymakers in Bangladesh should set their eyes on an "education for prevention" oriented approach to eliminate violence against half of its population and ensure their fundamental right to a life of dignity.

The writer is a freelance contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments