Contours of passion in poetic expression

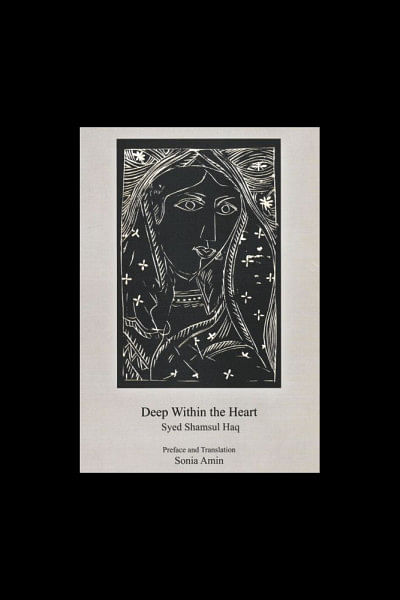

It was undoubtedly a challenging task and, I must say, it has been accomplished properly, by virtue of the tremendous confidence, acumenand ability of the vested quarter. Sonia Amin has translated the book Poraner Goheen Bhitorby Syed Shamsul Haq into English with formidable artistic skill. The English version,Deep Within the Heart, has been published by Bengal Publications in July 2016, just a few months prior to the demise of the Bengali literary maestro. The translation was challenging because it was a book of poetry written with an admixture of Rangpur dialect spoken in the northern part of Bangladesh. It is almost impossible to transfer the same taste and tone from the original to the new text in the new language. There is every risk of losing the intricate cultural and emotional content in the decoding and recoding process. The translator has adopted a special technique to check this. She has kept the dialect words, in ranges of the cases, intact and annexed definitional notes at the end of the book. It has ridded her of the complex burden of talking in a roundabout way.

Poraner Goheen Bhitor, a collection of 33 sonnets marked with numbers rather than titles, was published in 1981. Syed Haq, sailing on the modernist waves, wanted to infuse traditional local colour into mainstream Bengali poetry. He focused on the problem of language and presentation in search of a new style of his own. He was stirred by the subtle difference in meaning of the two apparently synonymous phrases like 'elomelochul' (disheveled tresses) and 'aulajhaulakesh' (messed-up hair) and he was thinking whether he could hit the delicacy with his poetry. He touched on the richness of folk forms, took into account the lives of rural people and versified them into his sublime craft. It was a significant attempt to embellish Bengali poetry with unfamiliar essence of flowers—an effort to combine 'acquisition of modernism with indigenous cultural sensibility', as the translator has observed. Similar trend we witness in Sonali Kabinby Al Mahmud, another poetic master of contemporary Bengali literature. It heralds a new dimension of Bengali poetry, which enthralls the audience with a sense of 'indigenousness' deeply rooted in the history of the peripheral mass.

Syed Haq made it clear in the preface why he decided to break new ground and how he went through the process. While he was writing these sonnets, he felt time and again the presence of generations of unknown poets who lived long before him on the soil. He enjoyed engaging with them in a creative interplay, blending his own entity with the form and content, style and context of those rural bards. While Sonia Amin was translating the poems, she visited the poet's house and talked to him in person. She got things explainedby him for the sake of a lucid rendition. The poet encouraged her to go on with her project as he felt encouraged himself. The translation remained close to the original as desired.

In translation of poetry, the original sound treasures and the nuances of meaning are often lost along with the loss of rhythmic and rhyming patterns. Sonia Amin took utmost care not to distort the original message. She dived deep into the word-pool and found out what is best to express a certain idea. She admitted she used the word 'broth' for 'torkari' (curry) while she avoided using 'pancake' for 'pitha' and 'chair' for 'peera' (low wooden platform for sitting). Such Bengali words are laden with subtle cultural meaning apart from their surface denotations. The phrase 'blue sari' could not satisfy her mind, so she used 'simmering blue cloth' instead, as a translation of 'nil sari'. This way, bit by bit, with workings of brain and heart, she completed her mission, yielding a laudable work in translation.

The romantic relationship between man and woman, their love and passion, physical and mental attraction, union and separation, joys and pains, amid nature and rural culture, have been wonderfully depicted in Deep Within the Heart (Poraner Goheen Bhitor). I curiously went through the whole bilingual volume, comparing the Bengali poems with their English versions. And I was impressed with the quality of work. The translator has maintained the fourteen line scheme, as fixed in sonnet, with an accuracy of language, lexically and syntactically, capturing the inner message as much as possible. She has translated with recourse to apt metaphorical language with ingenuity. "My heart grows heavy – the sun sinks low". The image of the sun sinking low is much more vivid than "bikal" (afternoon) as it was in Bengali. We may read some other reverberating lines:

Why does the cruel wind toss the dry leaves about?

Who weeps there on the edge of the field?

Why do I see the corpses wherever I turn?

I have seen what there was to see, what now?

No book, no work of translation is fully free of flaws. This book has also its own limitations, though not of major types. In the Bengali form, a line is of eighteen matras (syllables) within what is called Akkhor britto Chhondo. This could not be, and practically cannot be, maintained in translation; just as one would not expect the maintenance of rhyme scheme. In English the lines have been of unequal length of varying count of syllables, not molded in any specific meter—iambic or trochaic or any other. Some lines have been made unnecessarily longer or shorter than others. For example: "Is there no journey where the mythical boat does not sail on the wings of the wind." Just it could be, for the sake of brevity, in consistency with the Bengali sentence: "Is there no journey where the boat of wind is absent (Sonnet-33)." Similarly, "The lure of the trees, the pull of the poison vine is greater than yours of mine" (Sonnet-31) could be shortened as: "The pull of tree and poison-creeper is greater than yours." The examples of oddly placed shorter lines are: "Dress in your loveliest" (Sonnet-9), "Won't you open the door?" (Sonnet-24), "From the sky above" (Sonnet-27), "Only one favour I ask" (Sonnet-29), etc. Poetry, in particular sonnet, is not simply the arrangement of meaningful words and sentences; it is also the beauty of structural symmetry.

In the last two lines of Sonnet-30, the translation has strayed away semantically, along with the problem of unequal lining: "Pay your debts now, woman, in the currency of love, for what you crushed underfoot / Those precious, golden vines – those rare suspicious roots." The original lines wanted to say something else. The similar problem has occurred with lines 10-11 of Sonnet-15: "Will this drive you out of your home, like a farmer, who has lost all? / Will you not be overcome then?" which does not conform to the original message.

In other places there have been little glitches of diction. For example, the last line of Sonnet-1 has been translated as: "Is one who unfurls colored kerchiefs deep within the heart" whereas there is no mention of the handkerchief's being "coloured" in the original poem. In Sonnet-14, "Green fields" in the second line has been inserted superfluously. Similarly, in Sonnet-4 in the first line: "Whose counsel should I seek – he scorns me night and day", the phrase "night and day" has been added, over the original, probably in order to rhyme with the next line ending with the word "away". Obviously, the translator has taken the freedom to add words for aesthetic reason, but at the cost of trustworthiness.

The translator has often broken down one Bengali sentence into two English sentences. This freedom she has taken particularly to strike rhyming in the concluding couplet. For example, in Sonnet-15, the last line in Bengali literally means: "Whereas I remain at home, I cannot live in this doom." In Sonia's English translation it has been: "But helpless I stay rooted to the spot / My wretched, loveless, empty lot." In other cases, the translator has reconstructed the theme of the line while arranging into two. For example, the plain meaning of the Bengali last line in Sonnet-17 is: "I elope with him leaving everything behind." Its English translation has been: "Home, hearth, hope – leaving everything behind; / and sail with him into the uncharted wild." The translator has also rearranged lines. For example, in Sonnet-15 parts of the 9th and 11th linesin Bengali version have appeared as the 8th line (How should I respond?) and 9th line (What power have I?) respectively in the English version. Probably this sort of freedom for alteration may be enjoyed by the translator, and it does not transgress the norms of translation, I suppose, provided it adds some value to aesthetics.

Despite all the limitations, as mentioned above, I must say, it is a good translation. Deep Within the Heart is a pleasant work which should be appreciated by any reader having interest in poetic art, and it offers double benefits for those having command over the two languages concerned. It is a love of labor on part of Dr. Sonia Amin, a Professor of History at the University of Dhaka, who has a glaring passion for literature and an enviable poetic taste which has prompted her to undertake the difficult task of translation.

Dr. Binoy Barman is Director, Daffodil Institute of Languages (DIL), and Associate Professor, Department of English, Daffodil International University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments