The Birangona beyond her wound

Merely days after the Liberation War ended in 1971, the government of the newly formed Bangladesh, in a historically unprecedented move, termed women who were victims of sexual violence during the nine months of the war as Birangonas (war heroines). This, along with the state efforts of rehabilitating these women, has meant that unlike the conventional attitude towards wartime sexual violence, the issue is not mired in silence within Bangladesh — there exists a public discourse and memory of the Birangona. However, this memory has also resulted in a portrayal of Birangonas as a generic figure, defined by the incident of the rape and disregarding how they dealt with the incident in their subsequent lives. Interested about this radical acceptance of survivors of sexual violence in her neighbouring country, Nayanika Mookherjee, now Reader in Socio-Cultural Anthropology at Durham University, decided to do her PhD research on the issue in 1996. Her work, which started in 1997, and spanning almost 20 years, has resulted in The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh War of 1971 (published by Duke University Press in 2015 and the South Asian version was published by Zubaan in 2016). The book, in her own words "argues that identifying raped women only through their suffering not only creates a homogenous understanding of gendered victimhood but also suggests that wartime rape is experienced in the same way by all victims." She suggests that this makes us unable to "see how violence is folded into the everyday lives of those who were raped during the war."

In an interview with Moyukh Mahtab of The Daily Star during the recently ended Dhaka Lit Fest, where she was a speaker, she elaborated on what drove her to do the research, her work and the implications of it for journalists, activists and researchers who work with the history of Birangonas.

Nayanika Mookherjee: The book is an ethnography, which means it is an anthropological project looking at various kinds of peoples' point of view about what I call a public memory of wartime rape during the Bangladesh war of 1971. This involved working with survivors of rape during 1971, various state and human rights activists dealing with the issue in the 1990s, as well as an exploration of the 40 years of visual and literary representation. So it's a triangulation of these three things that constitute the project itself.

TDS: How long have you worked on the project and what did it entail?

NM: Maybe I should start with why I did the project. For me, the reason for doing this work is linked to 1992, when I was a second year undergraduate student in Kolkata. Babri Masjid happened, and there were all these rumours of inter-community rape of Hindu women by Muslim men and Muslim women by Hindu men. From a feminist sensibility, I thought about why men are killed and women are raped — why does that happen and what does it mean?

Secondly, at a time like the 1990s, international events like those of Bosnia and Rwanda were happening. So laws about rape as a war crime were being defined; Japan was being asked for an apology. Also, a huge amount of partition literature came out in the 1990s — by the likes of Ritu Menon, Urvashi Butalia, Veena Das — which was bringing out how during the partition, there were these instances of women being subjected to what was seen as 'abductions', across communities.

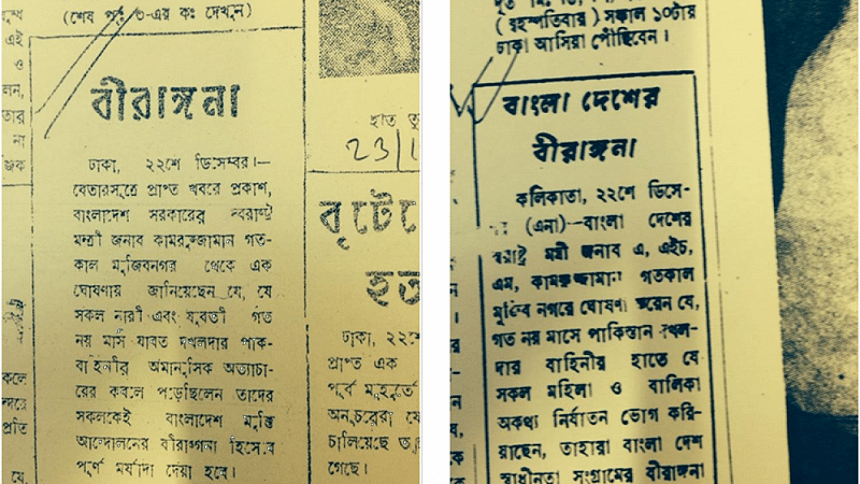

The third point, which was what had happened in Bangladesh, was very notable. I had known that the government after the war had referred to these women as Birangonas, which as I have known over the years till now is an unprecedented move. Yet it is known by very few people outside Bangladesh, and even within Bangladesh, it is not particularly highlighted as something that was quite radical. This was happening as early as December 23, 1971. That's 7 days after the war that Qamaruzzaman announces that women who were raped by the Pakistani army would be called Birangonas, and when Sheikh Mujib comes back from Pakistan, on 10th January and onward, he popularises the term even more, by referring to the Birangonas as "my mothers and sisters." It was a pretty radical position and yet I was reading constantly that 'there was complete silence about it.' To me a state declaring women as Birangonas was not silence at all, even though people might not take it well or it might have various kinds of repercussions.

"These women are carrying on with their lives. The injury of what happened is coming up in different ways, it need not be something sensational like the understanding we have of the Birangona. Otherwise we would never understand what happened to the Birangonas in terms of their experiences of the war."

I arrived in Bangladesh in March/April 1997. The following day I came across stories of Birangonas in the newspapers having come to some felicitation ceremony. I worked out a lot of things in that one month. I was absolutely gobsmacked by the publicness of it. There was no silence, people were talking about it in different kinds of public forums.

Then I came back in September 1997 and stayed for another year, and that was when I did my main field work. I decided that the ethical thing to do would be to follow people who had come out publicly in the newspapers. And primarily among them were four women who had come public. I stayed with them in western Bangladesh for eight months in their village. I also did a lot of work around the area, so I covered other districts in western Bangladesh. I was looking into the women, the human rights testimonies, human rights activists. During the winter and spring, I worked among the women, and when the rains started around July, I came back to Dhaka and did the archival work in Agargaon.

TDS: You use the idea of achrano (combing) as a metaphor of what these women experienced.

NM: The metaphor of combing came to be from a comment made by an Anthropology student in Jahangirnagar University where I was giving a talk. I was looking at combing as covering, explaining a story of a woman's daughter who used to comb her mother's hair, and as a result, cover up the scar the mother had. While I was explaining that, the student pointed out how combing (achrano) also means searching. So for me combing became hiding and searching. In Bangladesh there is a public memory; so while the women are being brought out and talked about, their own personal life stories are being hidden or not put forward.

When I started following up on women who were willing to talk about it or had come out in the public, I found that many of them wanted to talk about the process through which their testimonies had been recorded rather than about '71. Before I went to western Bangladesh, I realised that something was amiss, and these women were not very happy about how they had been reported. So I went to this place and started getting a feel for the politics and history of the area itself. I started interviewing liberation fighters to not make the women conspicuous.

While I was doing that, one day one of the husbands of the women came over and said, "How come you are not coming and interviewing us, we are the main people for which this place is known. Why are you interviewing all these other people?" So they literally invited me over. But what is interesting is that their wives were very resistant. The husband would say "speak into the machine," as if the machine is meant for another wider audience. But the women were definitely resistant, saying "amar kaj acche, ami korbo na, amar shomoy nai." (I have work, I won't do it, I don't have the time.)

And yet what the women were willing to talk about was what happened to them in the 1990s. As you know these women were being brought back and forth [to and from Dhaka to give testimonies] and they were given lots of promises which were not fulfilled, and then when they went back to their village, the villagers would be jealous, and subject them to khota (scorn). The women would say that while they were given chairs to sit in Dhaka as a sign of respect, in the village the chairs were pulled away. So they were being made more vulnerable through this honouring process.

TDS: You make a differentiation between the words 'trauma' and 'wound'. You are more interested, not in the incident, but in their post-conflict lives. Could you explain why?

NM: I did not ask the women what happened in '71. To me what was important was what the women themselves wanted to talk about and how their lives have been after the war. As a result, what came out was how the violent experiences of these women emerged in all kinds of ways, which exist on an everyday basis, but which are not articulated in that kind of stark, 'traumatic' way.

For example, this woman, whom I will call Shirin, is a government official. I chanced upon her. And when I said I am looking for the experiences of women in government documents she scolded me by saying: "You think you will find experiences of birangonas, that too in government documents?" Then she started to talk about her first husband: they had been childhood sweethearts. During the war, her husband came to visit her, and soon after he came, there was a banging on the door. They realise he has been followed. So he asks her to go away and hide. He gets killed, and she is a witness. But then she gets found.

At this point Shirin is playing with the paperweight on her desk. And then she continues by saying: because of what happened to her during the war, she had to marry her cousin, for whom she says she has no respect, as she loves her first husband. Her second husband knows she loves her first husband more, so when she is praying, she is thinking about him and her present husband gets jealous. She has to keep the photograph of the first husband locked away in her office cupboard. For Shirin, her pain lies in not being able to talk about her first husband in her everydayness. And this is a direct result of what happened to her during the war.

So that's why it's important for us to work out post-conflict accounts, precisely to know how this violent experience had an effect on the women's subsequent lives. This is where the wound comes in. The Birangona is considered in Bangladesh as either being physically 'abnormal' or someone who has been ostracised from their family or community. I am sure these have happened, but that was not the only way Bangladeshi families dealt with these women.

"Then there are some nice stories too. One of the social workers said that at that time, many of the women did not want to get married. They were asking the state to give them the jobs they were promised. They were making the state be the state, they were demanding it of the state. Amake chakri den, ami keno biye korbo. Amar jokhon iccha hobe, pore biye korbo. (Give me a job. Why should I marry? I will marry later, when I want to.)"

I hardly use the word trauma because it has become this transnational word, which is supposed to stand in for something, like flashbacks. These women are carrying on with their lives. The injury of what happened is coming up in different ways, it need not be something sensational like the understanding we have of the Birangona. Otherwise we would never understand what happened to the Birangonas in terms of their experiences of the war.

TDS: The nationalist narrative of 1971 has resulted in a construct of a generic, traumatised Birangona. How does this tie up with the name of your book, The Spectral Wound?

NM: I call the book Spectral Wound because the idea links up with the idea of combing. It's a similar logic. I already explained why wound. She is either understood through her dishevelled hair, bleak look, muted sobs. Or the Birangona is assumed to be someone who is outside family structures, zones of nurturing.

Spectral Wound links up with the idea of the hiding and the searching. I take it from Jacque Derrida's idea of the Revenant — how something is present at the very moment of being made to be absent at the same time. The Birangona is made to be present while at the same time the complexities of her life story are completely removed or taken away. I will give you an example.

There was an enactment of an oral history project. The story is that this woman goes home because her two brothers have died from cholera. The Pakistani army finds her and rapes her. Her husband comes over from another village. She is very ill for a year, and her husband looks after her, takes her to the kobirej daktar. He is a kind sensitive man, and they are still together today. When this was re-enacted, it was portrayed that the woman lives at her mother's house, that her husband did not take her back and she has no contact with him.

And today, the problem for her — she is the second wife of the husband — is with the first wife, who would always raise the issue that her mother had to ask the husband to take her back. A khota emerges in the form of a competition between the co-wives in this instance.

In the enactment she has been made to be present with the horrors of the war, but immediately the complexities of being the second wife, that the husband had looked after her, have been completely taken out. She has been frozen, made to be present as a figure who is steeped in the horror of the war only.

And this has happened many times as I show in the book. Changing stories to make it horrific. I would say, why not keep the actual story so people understand the way in which people are actually living their lives and not think of her as something abnormal.

TDS: You also talk about literary and film representations of Birangonas in the post-war period. Do you see any change today?

NM: In the past literary and film representations the Birangona is predominantly a horrific figure. All Birangonas usually commit suicide or are made to exit the scene. The liberation fighters come in and protect her and save her. But there has been a huge change in the representation from 2000 onwards. I talked about that in the last chapter of the book. There's Shaheen Akhtar's Talaash, Yasmin Kabir's Aro Ek Shadhinota, and Tareq and Catherine Masud's Women and War, which go beyond the account of the Birangona as someone who is only horrific or 'abnormal.'

TDS: What are the ethical concerns that researchers, activists or journalists working with Birangonas should be mindful of?

NM: The main thing thing to give to this work is time. A lot of the work that happened in the 90s were very quick work. People should go properly and not be like "oh how did you feel" and in 10 minutes catch the bus back to Dhaka.

With time, there's the need to contextualise what happened locally. You need to ask other people their experiences so that you don't make the Birangona's interview conspicuous. So that others don't feel left out, and a jealousy economy arises which results in scorn for the Birangona.

The visibility that something is happening to them is what generates problems. So not making quick visits, not making them conspicuous, talking to other people, researching the local area. It is also important to set up a relationship with them.

For me what was important was not asking them what happened, letting them talk about what they wanted to speak about. There are other ethical concerns one has. I constantly wondered if I am also doing the same thing that I am arguing against and hence constantly tried to ensure that I was being ethical.

I met this man who told me that his mother was a Birangona and that she wanted to talk to me. I went with him, and asked his mother would she want to talk about this. She gets completely angry with me, she asks me to leave. She says if she talks about her account she will be pulled onto a stage, and her younger son won't give her bhaat. So it turns out the older son is jobless, and the mother is looked after by her younger son. She is looking out for her sustenance and talking about her rape might bring out problems for her. One can say to women: you shouldn't be thinking like this, everyone should be talking about this but only if they want to. Women also need to have the right to be silent, if that is what they wish as I have shown in my book. Overall we should do a risk analysis, before we work with birangonas.

TDS: How do you view the post-71 efforts of rehabilitation and adoption programmes, where the new state played a controlling role over the experiences and body of the Birangonas?

NM: What needs to be understood is, in the words of a social worker I closely worked with, Maleka Khan: "What were we to do? There were so many women. We had to bring them back to the framework of society." Yes, there was appropriation, but it was also very revolutionary.

It was after the war, everything was chaotic. Things needed to get back on track. I am currently doing this work on the adults who were adopted out of Bangladesh. So there's a British couple I have interviewed. The mother of the child who was adopted by them wanted to see the parents. She was a young, teenage mother, who said she needed to get on with life. But she wanted to see who this couple was. So at one level, women were happy to be able to get on with their lives. At another level, they did not want to look at the child at all because of its origin. At another level, as social workers would say, 'they had to protect women from the emotions of motherhood.' It's such a stark statement. We have to protect women from their own emotions of motherhood. You have to make them detached from their children so they can let them go.

In the newspapers in the early 70s, there was quite a lot about these children. While the state was willing to rehabilitate the women because of the sheer numbers of the women itself, it was very clear that the children had to be 'sent away', adopted away from the country.

There's one story told by a social worker, Maleka Khan about how they changed the age of women so that they could get jobs. There was this batch of nine women who got jobs, and today they are officially approaching retirement. These women are now coming back to the social worker and saying, "Remember you changed our age. You increased it. We are not at our retirement age yet, we have a few more years to work."

So there are these different ways that people are negotiating their history. So we need to think of the Birangonas not as a horrific wound and by not negating their complex life experiences. Instead we need to understand how their violence of wartime rape is folded in innumerable ways in the minutiae of their everyday life.

All photos, courtesy of Nayanika Mookherjee

Comments