New visions for the city

Described as "the toughest city in the world," and consistently ranked as unlivable, Dhaka demands new architectural and urban imagination if it were to escape from those tags. Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements presents here visions for an alternative destiny for Dhaka that can be actualised. Bengal Institute is dedicated to reimagining Bangladesh's urban future in which dire Dhaka and its regions can be transformed into a condition of civic, social and ecological wellbeing. The research and design team was led by Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, Director General, with Saif Ul Haque, Director, Research Program, and Md. Masudul Islam, Research Program Coordinator of Bengal Institute.

Dhaka is now poised for a new era. Positioned to be one of the most economically dynamic cities in Asia, Dhaka is predicted to be ranked at 48 by the year 2025 with an estimated GDP of USD 215 billion, way above Rome, Karachi, Hanoi and Montreal (UK Economic Outlook, 2009). Now ranked 31st among the world's largest economies, Bangladesh is predicted to take 28th place by 2030, and will be ahead of Malaysia by 2050 (in GDP figure by purchasing power parity according to PricewaterhouseCoopers).

But are our cities and towns ready for this forthcoming future? Is Dhaka prepared?

The future landscape of the country depends on what we make of Dhaka city. Any national plan will have to consider the urban scenario of the whole country, from the primary cities to the small towns, but particularly Dhaka city as it will continue to play a vital role in impacting places throughout the country. In the absence of a solid tradition of civic urban culture or infrastructural system, Dhaka city remains the sole model of urbanism in the country. It is ironic that every nook and corner in the mofussil (parts of a country outside an urban centre/rural areas) wishes to mimic the characteristics of a dysfunctional Dhaka.

New visions will have to consider the emerging urban landscape not as a knotty problem but as vast opportunities. Cities are not merely dire sites of institutional and social calamities that need constant remedies; if properly oriented and organised, they can be economic, social, and cultural engines. Bangladesh's potential for utilising its human resources in the new era of global economy remains largely untapped, and yet there are new ways by which Dhaka (and other towns) can be positioned towards a unique and desirable future.

Urbanisation has one meaning, and urbanism another. We urge the consideration of cities and settlements from the perspective of urbanism. Increasing population and physical growth, and their fallouts, mainly serve as the measure of urbanisation, but they do not necessarily make for a civic organism; they do not show how a city can be lived in its fullest human, social, aesthetical and ecological potential. From what was truly a garden city, Dhaka continues its predictable civic and environmental degradation. Even until the 1950s, with its spacious green spaces, majestic trees, crisscrossing canals, and civilised riverbanks, Dhaka presented itself as a garden city and a place by the water. With a new urban vision and political will and action, Dhaka can still be a unique, green and highly livable city that is also responsive economically and ecologically.

We have written about the prospects of Dhaka since 1996, in which we have constantly listed the following as parameters for a desirable future for Dhaka:

(1) A "good" city does not happen on its own; it is envisioned, planned in a professional manner, and then implemented with meticulous dedication. (2) Dhaka is an aquatic city and we tend to forget that. A recognition of rivers along with its banks and canals, and the various wetlands surrounding the city, instead of filling them up mercilessly, is crucial for an economic, ecological and cultural revitalisation of Dhaka. (3) Dhaka requires a radical restructuring of its transportation network in alignment with its dynamic physical and social transformation. (4) Buildings alone do not make a city, but buildings and spaces in a well-knit fabric. Urban spaces, such as parks, gardens, riverfronts, are precious ingredients of a city. (5) Housing is the material and social fabric of the city, and yet Dhaka has not been able to create suitable residential models for the many different communities that inhabit it. Alternative imaginative models of mass housing with greater density and higher quality of urbanity should be explored instead of promoting houses on individual lots and plots.

We present here few ideas at different scales and scopes that demonstrate how Dhaka can be transformed into a desirable city.

Dhaka's destiny lies in a regional plan

Dhaka is "growing" in its own happy rhythm, spurred on every now and then by fragmentary planning initiatives. This "growth" is neither relieving pressures at the centres nor creating a decent urban development anywhere for the city and its regions. Massive areas of precious wetlands and agricultural lands are being filled up to manufacture "urban land." It appears that the problems of Dhaka cannot be solved by looking only at Dhaka city.

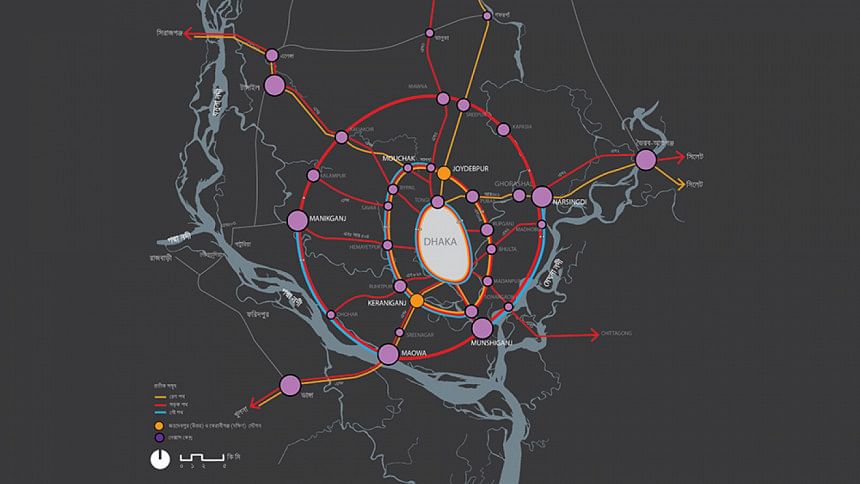

We propose a "Dhaka Nexus" in which the city and its greater neighbourhoods – the region – may be brought under a coordinated planning net. In the nexus area, selected existing nodes (settlements) may be revitalised by relocating and distributing commerce, institutions, and government offices in a uniform way. All nodes and hubs, old and new, may be connected by a coordinated transportation network. The nexus system can support the creation of multiple and diverse kinds of settlements, catering to different needs and experiences. Better quality of urban life in the nodes, with less travel time, will encourage decongestion in existing Dhaka.

Once the footprint of the expanded Dhaka is identified, nodes in the nexus and in-between areas could be carefully delineated so as not to affect more agricultural areas and wetlands. A rigorous balance should be established between Dhaka's urbanisation needs and ecological obligations.

Dhaka needs to spread out and yet remain connected for which transportation is critical. An organised, dispersed "city region" will have to rely on an efficient public transportation system that could be a combination of fast commuter train, light rail transit, extensive bus network, and riverway ferries and vehicles. Lessening travel time will be key for the performance of the nexus. In a fast north-south train corridor linking Dhaka and Mymensingh travel time can be reduced to two hours. It is possible that one could finish a day's work in Dhaka city, return to Mymensingh to an air and light filled residence, and enjoy a promenade along the Brahmaputra River in the evening.

We suggest three transportation rings around Dhaka that will be the organisational basis of the nexus. The first ring is located along the existing embankment roads of the city and may connect Tongi, Savar, and Keraniganj. The ring could be made up of an expressway, circular fast train line, and circular waterway. The circular road, river and rail system will connect stations along the lines. Radial roads and train lines from key nodal towns will connect towns and hubs in other rings.

The second ring may connect Narayanganj, Bhulta, Pubail, Gazipur, and Hemayetpur. Linking with the second ring, we propose creating two new major train hubs: one at Gazipur-Joydebpur as the North Station, and another at Keraniganj as the South Station. From the North Station, passengers can take faster trains to travel to northern and eastern districts. From the South Station, proposed as a new development hub, passengers can travel south, south-west and south-east.

The third ring may connect Munshiganj, Mawa, Narsingdi, Kapasia, Kaliakoir, Manikganj, and other towns and settlements. Radial roads and train lines from key nodal towns will connect areas in various regions beyond Dhaka.

The creation of this organised network of nodes is also based on a clear demarcation of the boundary of each node as well as that of areas that lie between nodes. In-between areas mean smaller settlements, villages, agricultural lands, forest areas, wetlands, flood-plains, etc. While each node may be planned and defined by distinctive types of residences, commerce, industry, administration, education or other functions, the in-between areas should also be carefully planned for their particular use and potential through land use.

Mass transit is the only traffic solution

Transportation is integral to everything critical to the life of a city: development incentives, land-use distribution, quality of civic life, environmental consequences, infrastructural arrangements, and economic betterment. While there are no instantaneous solutions to the complex issues of traffic and transport, we believe that by organising in an integrated way, and by genuinely understanding priorities, transportation investment can be the impetus for a new destiny for Dhaka.

Planners and policymakers need to consider whether Dhaka's transportation crisis can be solved by privileging cars or by mobilising for mass transit. In this city of 15 million and more, only a small percentage drive around in cars, and yet that small number disproportionately rules the roads, and dictates the terms of transportation, and consequently the life of the city. No amount of road widening and elevated roadways will make a dent to the problem. The only reasonable and effective response to Dhaka's traffic crisis is mass transit.

We identify three crucial sectors—rail, road and river—where new transportation modes may be implemented rapidly without too much infrastructural and construction challenges.

Buses continue to be the accepted mode of popular travelling, and may be expanded and organised for mass transit movement. A revision would require the inauguration of eco-friendly articulated vehicles carrying large number of passengers on dedicated routes. Special bus stands will have to be constructed that facilitate faster loading and transfer.

Water-based transportation system for Dhaka, with water-buses and water-taxis, is a natural choice in a waterborne geography. Water transportation can become an instrument to manage and control the riverbanks, and create hubs of riverside development and growth with new economic and social potential. The way Dhaka has turned its back to its rivers may be reversed by implementing a strong riverine transit system. The water link need not only be a circular one along the rivers, but like a vascular system within the city that can connect different canals and water bodies.

We eagerly await the metro rail system for that is the only answer to the traffic nightmare. In addition to the proposed lines in the metro, we also suggest a circular rail, road and river line going around metropolitan Dhaka along the embankment system, which is also the basis of the first circle in our idea for Dhaka Nexus.

Supporting the metro rail system, we suggest feeder corridors that can be based on a light rail system, one that can be built quickly. One such important possibility with a huge impact is an elevated light rail system from Khilkhet to Dhanmondi via Gulshan, Kawran Bazar and Panthapath. In order to encourage people to take mass transit, the proposed light rail can be linked up with the MRT Line 5 now underway. It is possible that the light rail can be built on the median of the existing roads for the most part.

A city with a successful transportation system relies on a culture of walking. For any kind of mass transit system, people need a proper and generous network of pedestrian arteries. That requires the construction and maintenance of proper footpaths that hardly exist in Dhaka.

New public spaces can make Dhaka a better city

It is simple: If Dhaka is to elevate itself as a decent city, it must reorganise the existing conditions of its civic and public spaces. The most crucial thing to do in this regard is to make Dhaka a walkable city.

The development of proper public places and civic spaces is central to Dhaka's transition to becoming a decent city, and the only way to erase the stigma of being unlivable. With a climate naturally suited to making a garden city, a bold design based on new imagination, and determined directives from two dynamic mayors of the city, Dhaka can again be a humane and positive place.

While open and public places define the civic realm of a city, sidewalks or footpaths are a key component of that system. The sidewalk, the most evident mark of the civility and humanity of a city, represents the culture of walking, strolling and promenading, and getting around without hindrance. This is particularly critical for Dhaka where more than 60 percent of the people walk. Such urban pedestrian systems as boulevards, promenades, riverwalks, or simple sidewalks that are the hallmark of all livable cities are for the most part non-existent in Dhaka. And if they do exist, they are in bits and pieces, and do not create a legible and defined network.

A proper walkable city is a civic right. The first crucial task is to revise our perception of sidewalks: A sidewalk is not the extension of a drain, nor is it a three feet wide cover over it; it is a space on its own, it is a public space. A sidewalk in Dhaka will continue to be used for multiple reasons especially for portable commerce and other improvisations. A guideline for sidewalk practices should be developed and maintained by proper regulations that embrace both the necessity of walking and the social interaction of commerce.

The pedestrian and the sidewalk is ultimately an indictment on the car, on its ultimate effect on the natural environment (through pollution, etc.), urban exchange (disintegration of the public realm), and social interaction (segregation of classes). Wealth and automobiles do not have to go hand in hand. Hong Kong is a good example where an integrated planning approach has succeeded in maintaining low automobile dependency despite Hong Kong's high per capita income and population density. The success of Hong Kong's pedestrianisation was possible due to the integrated network of pathways that separate car and pedestrian, and allow those pathways and sidewalks to be spaces of their own. A successful pedestrian infrastructure means relying mostly on a set of public transportation such as railways, buses, vans, trams, ferries, and such public spaces as elevated and moving walkways, tunnels, footbridges and generous sidewalks.

It is often overlooked that the overall transportation system of any city is intimately linked to the network of walkability created by sidewalks and public hubs. This is particularly evident in the case of Dhaka. With mass transit being the only way to counter the traffic woes of a city like Dhaka, the coming of the metro rail is highly welcome. But the success of the metro will depend on a walkable system: One will leave home for work, walk to the station, and get off at another station to go to the workplace or school or college. On a holiday, a family will walk off to a station to get to a public space to attend an event. After a family meal at an eatery and a walk by the promenade, they will catch another train to head back home.

In imagining exemplary civic spaces, we present ideas for two areas, one from the older part of the city, Buriganga Riverbank, and another from the newer part of Gulshan:

Buriganga riverbank promenade

Dhaka is a child of the Buriganga, and yet it turns its back to being part of the world's most dynamic hydrological system. A radical reclamation of Buriganga River and its banks on both sides is crucial for an economic, transport and cultural reinvigoration of the oldest part of Dhaka. The river can become a sustainable life-blood, and the riverfront a much more organised condition providing renewed recreational, civic, touristic, economic, and transport opportunities for the whole city. To create an active public promenade along the Buriganga connecting both banks, we propose:

Framing the river's edge with a new language of development appropriate to riverside activities: Riverbanks are encroached upon or abused because there are no exemplary models on how to use them. An appropriate riverside development will create a defined overlap between city and river, something that is now lacking.

Connecting north and south riverbanks with a continuous public promenade: For example, a promenade may link Sadarghat launch terminal to Badamtoli ghat, and via the bridge make a loop to the riverbank on Keraniganj. Walkways, ghats, terraces, gardens, floating islands, and pavilions – all part of a riverbank language – will form components of that riverside promenade.

Connecting civic and historic buildings and their sites, and newly proposed public and commercial centres, and large parks and gardens with new public pathways: A new generous plaza – Sadarghat Chottor – is proposed in front of Sadarghat terminal as a public gathering space and forecourt to the terminal where passengers and visitors may assemble. The terminal building can be renovated as a porous and transparent building with better efficiency as a passenger hub and visual connection to the river, as well as a landmark structure on the riverbank.

Generating an active water-based transportation by creating ghats and stations for river-buses and river-taxis: By bringing travellers and tourists from other parts of the city, stations can become hubs for new economic and cultural activities in the neighbourhood.

Civic corridor along Gulshan Avenue

Gulshan Avenue has seen much change, from being a quiet avenue for a planned residential district to a corporate and commercial axis. Despite a lineup of striking buildings, Gulshan Avenue still lacks a proper civic and walkable environment. There are no significant spaces for public gathering, places to go to, and no remarkable sites or structures to celebrate the avenue as a civic corridor. It is merely a road dedicated to the unruly car. The existing scenario can be better arranged with a new installation of exemplary public spaces, parks and pathways stretching from Gulshan-2 to Kawran Bazar via Hatirjheel. We propose the following:

Providing a new schema and standards for the sidewalk in order to create an organised walkable network that links key points, hubs and destinations: Gulshan Avenue itself can become a continuous walkable corridor providing for Dhaka an example of a proper tree lined, comfortable walkable street with the pedestrian as priority. A decent walkable city can reduce urban stress as well as transport crisis. If one can walk, there will be less need for driving.

Creating generous public places and plazas wherever it is possible (especially on city owned sites): A clearly doable project is to convert Gulshan 2 road intersection into a pedestrian plaza. This can be done by rerouting car traffic around the outer circle of Gulshan 2 in a continuous loop that will also ease traffic movement considerably. The plaza itself can be a lively gathering place for the whole area, as well as outdoor seating for adjoining businesses. On occasions, the plaza can be used for musical events, melas (fairs), flower shows and other events.

Converting selected city properties into a better and efficient public realm: The DNCC owned markets in Gulshan 2 area can be renovated into a proper civic centre with new shopping facilities, offices, auditoriums, but most importantly, walkable public spaces and passages. Such an arrangement is also expected to yield higher economic results. In developing each city property, multi-level underground parking is suggested to reduce anarchic parking on the streets.

Promoting parks and gardens wherever opportunities exist: Gulshan and Banani lakes are assets to the city. As an exemplary project, we propose strengthening the development of Gulshan Lake East as a recreational park and ecological zone. We also propose transforming existing Gulshan Park as a designated sculpture park with other art related programmes. A five-storey underground parking can be constructed below the grounds of the green park, along with community and food court facilities. Gulshan and Hatirjheel may be linked through green belts of parks, lakeside walkways and pedestrian corridors.

All images produced by Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments