Our ventures are unending

"Strange, ecstatic and fresh,

Our ventures are unending.

We defy limits.

Breaking gates open to life!"

Rabindranath Tagore

In the last few decades, South Asian and Southeast Asian countries have experienced high rates of labour force growth associated with high population growth. The growing youth labour force can provide an important input for accelerating economic growth. The experiences of rapidly growing economies of Asia also illustrate similar cases of utilising demographic dividends to accelerate economic growth. This segment is likely to be the more dynamic component of the labour market. In recent years, the shortage of skilled labour for the modern sectors is being felt by many countries, and in this context, the youth labour force can play an important role. For Bangladesh, they too may be considered the potential demographic dividend, and if fully utilised, they can help the country achieve middle income status.

Having a younger labour force requires separate analysis because this group faces distinct types of demand that are likely to be generated by separate sets of employers. The youth labour force may face additional vulnerability because of their age. The transition from school to workforce is often difficult, especially for youths from low income families who are likely to enter the labour force earlier than others.

This workforce has not received adequate attention in the context of Bangladesh's labour market. In the past, they entered the labour market smoothly through family employment, and this has contributed to the lack of attention. In an economy dominated by family employment, the entry of youth in the labour force is considered an automatic process where they are engaged as unpaid workers in family farms/enterprises. But this option may no longer be available as the youth receive education and aspire to move to new occupations and paid jobs.

The objective of the present discussion is to examine whether a potential demographic dividend exists in Bangladesh and how to utilise this. This is likely to depend on the growth of the youth labour force and the quality of their skills. It will also depend on the young people's actual participation in the labour force and unemployment rates in this age group. An analysis of recent changes in these indicators will be presented.

These analyses assume distinct importance in view of the fact that the youth unemployment rate and youth participating in tertiary education factor significantly in the proposed indicators of Sustainable Development Goals 4 and 8. Building a base of data and analysis of these categories can help monitoring SDG achievement.

Although various policy papers, including the 7th Five Year Plan of Government of Bangladesh, have highlighted the role of demographic dividend, research studies and actual policy and programmes on this issue have been lacking. Therefore it is urgent to work on the subject to identify the prospects of utilisation of the potential demographic dividend.

Potential youth labour force

The size of the youth population (aged 15-29 years) was 39.25 million in 2010 and 43.44 million in 2013. Labour force participants in this age group increased from 20.9 to 23.4 million during this period. The increase has resulted mostly from the growth of population in this age range. There has in fact been little change in the labour force participation rate.

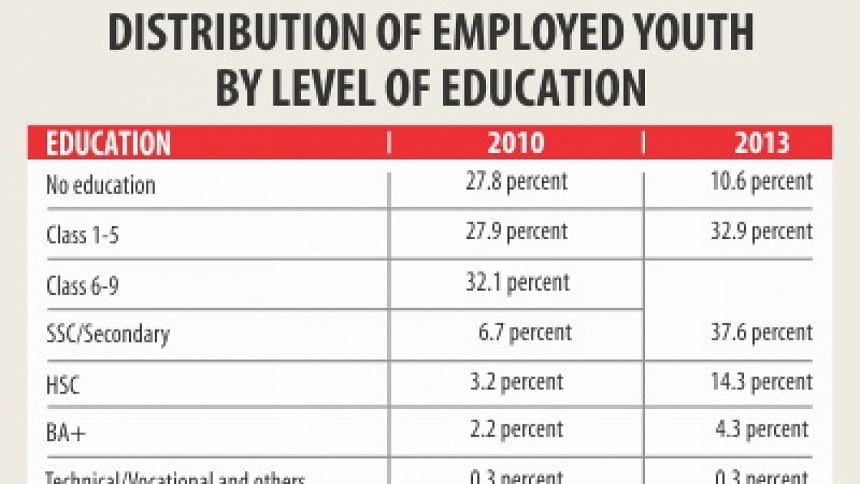

An important positive feature of the youth population is the improvement in academic qualification. Distribution of youth population by level of education is shown below. The shares with HSC and tertiary education are much higher in 2013 compared to 2010. Those without any education has declined from 28 percent to 11 percent.

Success stories

Bangladeshi youth who are "restless and ecstatic", in the words of Tagore, have shown dynamism in seeking and capturing opportunities. Their successful endeavours include accepting non-conventional jobs and pursuing entrepreneurship. Most important among these are in the areas of skilled and unskilled jobs in the RMG sector, overseas employment, innovative farming enterprises, ICT related enterprises, etc. Also, sports and cultural activities in Bangladesh are dominated by creative youngsters. Even within the limited scope of this discussion, some details of the first two may be highlighted.

During the last two decades, the export oriented RMG industry has flourished, and at present, RMG export constitutes more than 80 percent of the total export earnings of the country. Availability of cheap labour has been one of the most important factors behind the accelerated growth of the sector. Employment in this sector stands at four million at present, of which 60 percent or more are under the age of 30 years.

Moreover, the majority of workers (about 60 percent) in this sector are young women who have migrated from the rural areas. Working in an urban factory environment has been an absolutely new experience for these young women. They work for long hours and the work is tedious. The wages are such that they can afford only a modest standard of living, to say the least. Working conditions have been unsatisfactory in many instances, especially during the initial years. Amidst confrontational politics in the domestic sphere and changes in the economic environment, the untiring effort and enthusiasm of unskilled young workers has contributed to the growth of this sector.

The other remarkable success of Bangladesh's young jobseekers is in the sphere of overseas employment. During the last one and a half decade, about 0.5 million obtained such jobs every year and about 40 percent of them were under the age of 30 years. These jobs were mostly of the unskilled nature, involving hard manual labour in a difficult environment. At the outset, the prospective migrants had to take up various risks and the cost of migration has been high compared to other South or Southeast Asian countries.

Those with low education cannot share the benefits of modern technology based manufacturing and service sector jobs. Such technological divides will lead to further income inequality, and create a segmented labour market and a lack of inclusive development.

Challenges faced by young jobseekers

Although they are willing to take risks and accept jobs in adverse situations, young jobseekers face many challenges in the process. These challenges are reflected in the level of unemployment, low earnings, and discouragement/ delays in entry into the job market.

Data presented in the 2013 Labour Force Survey of the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics shows that unemployment rates are higher among the youth compared to those aged 30 and above. Moreover, it is higher among those with some education, especially among those with tertiary education. An obvious question is why this is happening? Education is supposed to increase employability. Then why is the opposite being observed?

Two simultaneous forces may be at work. First, the type and quality of education is such that it does not increase employability. Second, sufficient job opportunities are not created due to a host of factors. In truth, a graduate degree may not be enough to fetch a good job in the present day world. This has been revealed by studies in high income advanced economies as well.

Considering the unemployed and youth not involved in studies or the labour force, in 2013 about 33.5 percent of the youth population remained unutilised. This share has declined from 38.6 percent in 2010, which of course is a positive feature. This indicator (not in employment, education or training: NEET) has been suggested for monitoring SDG 8 on productive employment.

The youth labour force earns less than adults in general, and the youngest group (aged 15 to 19 years) faces the greatest disadvantages in terms of earning because they enter early and without much education. Educated youth obviously earn more than those without education. Benefits in terms of higher earnings and progression of earning with age occur only among those with secondary or higher education.

Case studies illustrate that a large segment of young students at the tertiary level are willing to enter the labour force if "suitable jobs are available". They pursue higher education because they have no other option and do not wish to be considered as "unemployed". Projections of future employment need must take this feature into account.

Technology and inequality

While considering the prospect of utilisation of the youth population for accelerating Bangladesh's growth, it must be recognised that they do not constitute a homogenous group. Inequality among the youth population is linked with sex, location, family economic standing, etc. These differences can result in unequal access to education, training, and quality of jobs. As mentioned above, youth labour force is expected to be better equipped with technological know-how. At the same time, past research by this writer shows that compared to higher income groups, a much smaller share of youth from households of the lowest two income quartiles are enrolled in tertiary education. A similar difference has been observed among men and women. Those with low education cannot share the benefits of modern technology based manufacturing and service sector jobs. Such technological divides will lead to further income inequality, and create a segmented labour market and a lack of inclusive development. This will lead to frustration among those who fall prey of inequality. Lack of inclusive development can nullify the benefits of development itself.

Policies for better utilisation of youth labour force

Better utilisation of the youth labour force who are unemployed or not seeking employment obviously requires creating more and better jobs by directing macro policies for labour intensive growth.

In addressing the unemployment problem among the educated, skill training rather than general education is often emphasised. But access to training is linked with general education. So while short and medium term training for raising employability is essential, it must be emphasised that the expansion of training must be accompanied by quality improvement of technical and vocation education training (TVET).

Poor quality of education and training may start a vicious cycle. Expansion of training of subpar quality and without proper assessment of demand may result in unemployment among the trained. They may end up in jobs that do not utilise their training and/or provide low wages. This discourages future demand for TVET and sets in a vicious cycle where those with poor performance in general education only go for TVET, resulting in poor performance of TVET and poor quality of jobs with low earnings. Thus, the only thing that can break this cycle is the simultaneous improvement of TVET and general education.

The writer is Executive Chairperson, Centre for Development and Employment Research.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments