Taking responsibility for our future

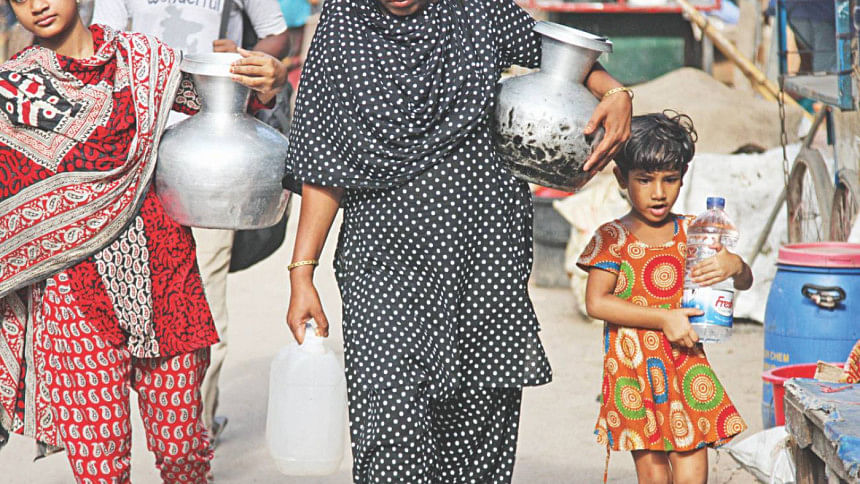

There is no greater natural resource on this earth than water, as without it, life on this planet would cease to exist as we know it. But because the majority of the Earth's surface is covered in water, it is difficult for most people to imagine the types - and severity - of problems that the scarcity of safe drinking water is increasingly creating around the world at present.

On World Water Day, seven years ago, today, the then United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon said that more people were dying in the world from unsafe water than from all forms of violence, including wars. According to the '2014 World Water Development Report' released by UNESCO and UN-Water, 240 babies were dying from unsafe water every hour of every day. Another 2013 UN report estimated that 783 million people did not have access to clean water at the time of its release.

Moreover, unless we as a species "manage" our water resources "more effectively", the world's fresh water availability will fail to keep up with its demand by the year 2040. This will cripple the "ability of key countries to produce food and generate energy, posing a risk to global food markets and hobbling economic growth", says the UN (World Water Day: Why it matters, CBS News, March 22, 2013).

Bangladesh too faces these risks, as well as some of its own. For example, two decades after it was discovered in Bangladesh's water supply, about twenty million people in the country are still drinking water contaminated with arsenic - a potentially deadly toxin (Twenty million people in Bangladesh drinking water contaminated with arsenic: Human Rights Watch, ABC News, April 6, 2016). This, the Human Rights Watch says, leads to the death of about 43,000 Bangladeshis every year, particularly in poor rural areas.

The reasons why this issue has remained so pervasive, according to the rights group, are because of poor governance. In the absence of proper oversight, politicians earmark new wells for their own supporters rather than placing them in the worst-affected areas. This means that the situation has remained "almost as bad" as it was, "15 years ago". In fact, according to the World Health Organisation, Bangladesh's arsenic crisis is "the largest mass poisoning of a population in history" and would result in the death of millions if not urgently addressed.

Another cause for concern is the drastically decreasing groundwater levels, even in cities like Dhaka, because of excessive extraction to meet growing demands. As Dhaka's underground aquifers are refilled with underground fresh water from its nearby districts, which too is on the decline, the risk of seawater seeping into the aquifers is gradually increasing. If allowed to continue, this could, over time, make Dhaka's drinking water undrinkable, according to experts.

Amidst all of this, what is perhaps most tragic is just how thoughtlessly we are polluting and destroying our rivers and other water bodies, which directly affects the lifestyle and livelihood of thousands of people, if not more, living in this country, in more ways than we can imagine. Despite the concerns, not only isn't the situation getting any better, but it is actually getting worse by the day. Reports of how our water bodies and rivers are being damaged irreparably have become such a daily routine that it has reached a point where no one seems to care about it anymore.

And this is perhaps what is most concerning - that we have taken the supply of fresh drinking water and our rivers and other water bodies that play a key role in guaranteeing that for now, for granted. And, hence, are not caring for them enough, which is putting them and our availability of fresh water at risk.

And it is not only us who have failed to appreciate the value of, having available to us, this most basic human need, which has allowed for a very disturbing global trend to set in. That is, the growing privatisation of water across the world. Only a few years ago, Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, the former Chairman of Nestle, which is the largest producer of food products in the world and a major player in the bottled water industry, said that "access to water is not a public right"; nor a "human right", and thus, called for water to be privatised (The Privatisation of Water: Nestlé Denies that Water is a Fundamental Human Right, Centre for Research on Globalisation, August 29, 2016).

In response, Indian scholar, environmental activist and one of the leaders and board members of the International Forum on Globalisation, Vandana Shiva, said: "Since nature gives water to us free of cost, buying and selling it for profit violates our inherent right to nature's gift and denies the poor of their human rights" (Humanity's Big Fight: The Corporate Ownership of Food and Water, Natural Society, September 5, 2015). Yet, despite the risks associated with handing over the control of the world's water supply to some of the biggest multination corporations, the World Bank (WB) too has been advocating for its privatisation (World Bank wants water privatised, despite risks, Al-Jazeera, April 17, 2014).

It has, in fact, been doing more than that - becoming the largest funder of water management in the developing world, with loans and financing channelled through its International Finance Corporation (IFC), promoting water projects "as part of a broader set of privatisation policies". Perhaps unsurprisingly, however, its own data shows that a high percentage of its private water projects are in complete disarray. For example, according to the Al-Jazeera report: The WB's "project database for private participation in infrastructure documents a 34 percent failure rate for all private water and sewerage contracts entered into between 2000 and 2010, compared with a failure rate of just 6 percent for energy, 3 percent for telecommunications and 7 percent for transportation, during the same period."

Why then is the World Bank advocating for the privatisation of water, when there is overwhelming evidence of such schemes turning out to be major disasters all across the world? Is it not time for us to wake up and ask such questions? Is it not time for us to have a say in the future of the world's - and our own - fresh water supply? Are we really going to let private corporations, which are most responsible for polluting the world's water supply, now take full control of it? Can we really not see why that is such a terrible idea?

Instead of going forward with such rapid privatisation of water, I would like to propose an alternate solution to the coming crisis. That is that we, as individuals, take responsibility for our own local water supplies; collectively pressurise our respective governments to take responsibility for our national water supplies; and as human beings, cooperate with each other, to ensure that access to safe drinking water for all is prioritised above all, as despite what some may say, water is, indeed, a 'public and human right', and a most important one at that.

The writer is a member of editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments