ARCADIA ON THE JALANGI

The Potters of Ghurni

The Jalangiriver snakes across Bengal, as changeable as it is beautiful and impervious to the political divisions that would separate the eastern arm of its mother river Ganga from the western.

The potters of Ghurni on the riverbank of the Jalangi just above Krishnanagar, brought there from Natore by Raja Krishna Chand in the 18 th century, make clay busts of celebrated figures: aside from an unimpeachable deity such as Durga Rajrajesvari, Chaitanya and Rabindra,for example, Netaji and Aurobindo.

Occasionally the potters shape a full-length figure but more often settle for the usual head-and-shoulders bust and so we are not reminded of the old saying that warns us even our saintly heroes have feet of clay.

It is unlikely the potters were ever commissioned to make a bust of the man who 230 years ago took up position on the same riverbank just below Krishnanagar and, in a more intellectual way, gave shape to figures that were then not at all known to the world: Valmiki, Vyasa, Kalidasa.

The Law-Giver

Sir William Jones, for it was he who shared the riverbank with the potters, was part of an emerging British Raj in 18th century India and so is not free of the charge that, although espousing democratic, even republican, principles, he was, as a judge in Calcutta, part of an autocratic regime. Even on the issue of the abolition of slavery, of which he had been an early advocate, in India he found himself back-sliding.

It is also so very easy now to fault Jones for things he got wrong intellectually that we can as easily forget we are faulting him from within the comprehensive field of comparative cultural studies that his researches into classical Arab, Persian and Indian civilization originally opened up. As Jones himself justly observed of the work of the Asiatic Society of Bengal which he founded in 1784 and to which he himself contributed so largely, the world, instead of being surprised they had done so little, should wonder they had done so much.

Jones, able to marry and settle down as a result of being appointed a judge in India, hoped beyond his workaday duties to superintend the compilation of a Digest of both traditional Hindu and Mahommedan Law that would make public the principles of jurisprudence by which the new regime would be guided.

Jones was particularly keen in what for India had been an anarchic century to re-establish those traditional laws of contract and inheritance that would permit the development of agriculture and the mechanical arts and so guarantee, he hoped, the happiness of the 24 million people in Bengal (including then Bihar).

This visionary task, a rather unlikely alternative to the framing of the American constitution he had hoped to have had a hand in, though supported by the Government, was never completed in his life-time and in the event, not only drove him half-blind and hastened his death, but also proved less far-reaching and durable than he had hoped. His ideal as a law-giver was Solon but riverine Bengal no less than wolverine Britain was changing course and declined to comply with his Athenian model.

The Hellenist Vision

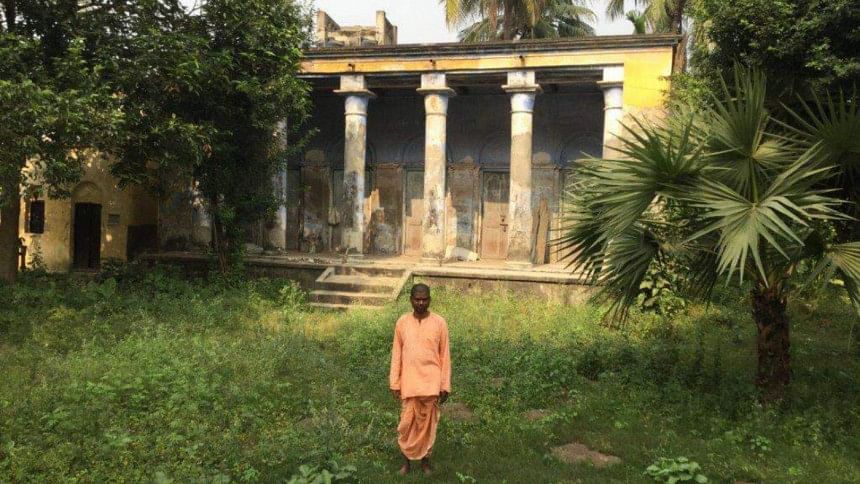

The Greek parallel was especially in Jones's mind when, in the autumn vacations, he together with his wife Anna Maria would repair to the banks of the Jalangi free of the court work that confined him in Calcutta. He was never unhappy in England, Jones said, but he never was happy till he was settled in India. The "charming plain" on which his traditional mud and thatch bangla stood he describes as Arcadia and the only spot that ever remotely rivalled it for him was at Jafferabad near Chittagong, experienced when the Joneses made a tour of the Delta early in 1786.

In a serial letter to his old pupil, the Earl Spencer, written over several weeks in the autumn of 1787, Jones explains why he is so happy. Imagine, he tells Spencer, an inquisitive Englishman arriving in modern Greece to find there is a classical Greek literature unknown to the rest of Europe in the hands of a few priests and philosophers: how much pleasure he will have in discovering the works of Homer, Plato and Pindar. Jones sees himself in a comparable situation in India: time for a Renaissance indeed and this time not confined to Europe.

Jones playfully extends the conceit, even referring to the Krishna-nagar he dates his letters from as Apollinopolis or Apollo's Town, having drawn a cultural parallel between Krishna and Apollo. It is in the bangla on the Jalangi that Jones, while working on professional legal texts, has the leisure to indulge his literary tastes in works like the pastoral Sakuntala (the plot of which he teases Spencer with over several letters, ending each like a story from the Arabian Nights) and the seasonal Ritusamhara. The first he famously translates, the second simply publishes in the original so that it may become more widely known in India.

Linguist& Poet

The very reason Jones has taken up the holiday cottage where he has is so that he can be close to Nadiya, otherwise Nabadwip Dham, the place he comes to refer to as his third university (after Oxford and Cambridge): here, he declares, he will finish his education. Already a master of several oriental languages, he hopes to learn the rudiments – and secrets - of Sanskrit, that venerable language "once vernacular in all India". Clearly he has imbibed the sentiment expressed in the Chaitanya Bhagavat: "If people read in Nadiya they find the ras of learning".

When his initial attempt in 1785 apparently received some check, he crossed to Krishnanagar where he stayed with the man who was then Acting Collector, Judge and Magistrate in the new dispensation, James Redfearn. Here he was helped to find a pandit to teach him the language of the gods by the Raja, Siva Chand, son of parents famous for patronizing so many temples and tols in the district that was then (and still is) sometimes, confusingly, called Nadiya- a reminder that the town, when capital of Bengal and before the Bhagirathi decided to rearrange the landscape, had stood on the same side of the river as Krishnanagar now did.

The polyglot Jones made such swift progress in Sanskrit that he had won over many among the pandits who frequented the more than one hundred colleges or seminaries in Nadiya by the time he came to compose his first original couplet in Sanskrit: the Raja, whose support was undoubtedly decisive, had his little son learn it by heart. It was allowed that Jones, if not a Brahmin any more than his teacher, Ramalochan (who, though a Vaidya, was a teacher of Brahmins), could be counted as a Kshatriya.

Jones was no less of a visionary about the future of literature in England than he was about the law in India. Saluted as a poet in Britain, especially for his charming neo-classical version of a ghazal by Hafiz ("Sweet maid, if thou wouldst charm my sight;/ And bid these arms thy neck in fold;/ That rosy cheek, that lily hand,/ Would give thy poet more delight/ Than all Bocara's vaunted gold,/ Than all the gems of Samarcand…"), "Persian" Jones now sought to further revivify English poetry by introducing into it a whole new Indian mythology.

Unlike Hafiz, who though invited never did make it to Bengal, Jones sits on the bank of one of its rivers composing "Hindu Hymns", none so immediate as his celebration of the Ganga, where he records how, in its manifestation as Bhagirathi, it "girds fair Nawadwip, thy shaded cells,/ Where the Pendit musing dwells…"

While it is his discovery or recovery of classical Sanskrit literature for which he is chiefly celebrated, Jones continued to extend his knowledge of Persian poetry, transcribing and translating Indian poets writing in Persian, still the court language. He spent a lot of time with the works of his fellow polyglot, Amir Khosro of Delhi, and was familiar too with that of the free-thinking Bengali-speaking poet, Bidel.

Jones did have some impact on the course of English literature, though the tidal bore of Romanticism overtook the 18th century current of his own poetry. It was not the novel oriental imagery that had an effect so much as a new Vedantin or Sufi spirit that accorded with the Platonic. The sensibility that infused the translation of Sakuntala, and much else that he made known about Indian poetry, inspired Shelley in his finest flights.

Similarly, the poetry which adorns Jones's Persian grammar had a decisive influence on Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, a century ago the best-known and perhaps best translation of oriental poetry outside, among other Biblical books, the Song of Solomon (possibly a poem brought to Jones's mind when he made a translation of another out flowing of riverine Bengal, Jayadeva's Gita Govinda).

Notes from Arcadia

In his long letter to Spencer of 1787, reflecting what is a happy as well as productive annus mirabilis, Jones perhaps has in mind a rubaiof Khayyam'she has lately translated (The Vanity of Kingly Grandiosity) when he contrasts their Bangla favourably with the marble palaces of Italy. He boasts that their thatched cottage, with an upper storey and a wide veranda all round, is built entirely of vegetable substances, free of glass, mortar, metal or any mineral bar iron nails.

In the "several acres of meadow and garden ground" around what Jones, after translating Sakuntala there together with Ramalochan, refers to as their "hermitage", they have flocks and herds eating bread out of their hands, he tells Spencer's mother, and, in an echo of the line in Isaiah concerning the millennial moment when the wild animals and the tame will lie down together, records how a tiger-cub and a kid, both fed by a she-goat, are playing at Anna Maria's feet.

By the time the Joneses go so far as to purchase the estate the following year (allowing Jones to playfully declare himself an Indian zamindar), they are deeply engaged not only in turning over the leaves of ancient Indian texts but those of the surrounding plants and trees. Savants and servants alike, pandits and peasants, are dispatched to every corner of Arcadia to collect botanical specimens unknown to Linnaeus, some likely to prove useful as well as beautiful.

Here are the leaves of the mahua with its intoxicating properties well known to the peasantry (and the dacoits); here the bael that, when its fruit was green, might have relieved Anna Maria of her persistent dysentery; and there a leaf from the last survivor of the palasi grove that had formerly distinguished Krishnanagar even more than the neighbouring town from which Clive took his title.

(To be concluded in the next issue)

John Drew is a poet from Cambridge who also writes about cricket, most recently in the December 2016 issue of the ESPN Cricket Monthly. He was travelling in rural Bengal recently and on returning home started to look into the history of one small patch of it.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments