Putting Consumers Last

When Abdullah Shibli Sadiq got a call from an unknown phone number informing him that he would receive a reward of Tk 62,500 from the government, he was astounded. At first, he thought it was a prank call. But when the caller asked him to come to the office of the Directorate of National Consumer Rights Protection (DNCRP) to collect his reward, Abdullah finally put two and two together.

In October 2015, Abdullah, a customer of Grameenphone (GP), purchased a 1 GB internet package at a cost of Tk 275. The package included 2 GB bonus data which, according to the offer, he would be able to use for the next 28 days. Although GP mentioned the price of the package as Tk 275, the company charged Abdullah Tk 325.74 when he purchased it. He also received a message from GP stating that the bonus data would expire within seven days and that it could only be used between 2 am and 12 pm.

"I was shocked and infuriated!" exclaims Abdullah. "I was wondering what I could do about such an act of cheating. Upon learning about DNCRP from the newspaper, I explored their website to find out how to file a complaint. Then I took some screenshots of the relevant messages and the advertisement of the package and filed a complaint."

Abdullah filed the complaint at the head office of the DNCRP stating that GP had lured him to buy their product with false advertisement and by concealing information. Upon investigation, the DNCRP officials found GP guilty of duping a customer and fined the mobile company Tk 2.5 lakh.

According to the Consumer Rights Protection Act (CRPA) 2009, the complainant is entitled to receive 25 percent of the fine. As such, Abdullah was rewarded Tk 62,500 on February 19, 2017. DNCRP officials state that it took more than a year to resolve the case as it required coordination with BTRC. Most cases are solved within seven working days.

What are the Anti-Consumer Rights Practices?* To sell or offer to sell any goods, medicine or service at a higher price than the fixed price under any Act or rules |

Know Your Rights

Prior to filing the case, Abdullah had little knowledge about his rights as a consumer. In fact, very few people in Bangladesh are aware about the Consumer Rights Protection Act 2009 which has mandated an entire directorate with the task of protecting consumer rights in Bangladesh.

Under the law, consumers can lodge a complaint if they experience anything that violates consumer rights – such as selling a product or service at a higher price than the MRP, adulteration of any goods or medicine, deceiving consumers by false advertisement, conducting any action that can endanger the life and security of the consumer and so on. However, since the enactment of the law in 2009, only 794 complaints were lodged till 2015, which highlights the severe lack of awareness among people regarding the law.

In 2016, the DNCRP launched a social awareness campaign to make consumers cognizant of the legal options available to them. The officials opened a Facebook page to disseminate information about the law, rules about filing complaints online and offline, and verdicts of resolved cases.

"In addition, the directorate has been arranging seminars, public hearings, and essay competitions as part of its public campaign. Thanks to these initiatives, in 2016, 1,622 complaints were lodged and, this year, 1,682 complaints have been lodged within just three months. We have formed 13 committees which regularly arrange hearings on the complaints and try to solve them as soon as possible," informs Md Shafiqul Islam Laskar, Director General, DNCRP. Since 2016, with a limited manpower of 240 employees (with 95 vacant positions), this organisation has been doing a commendable job of making the complaint procedure easy and accessible to the public.

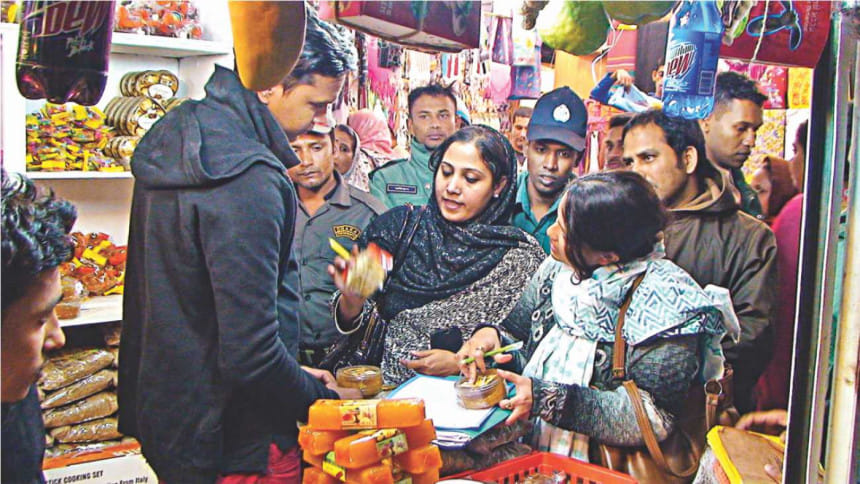

Consumers can now file a complaint simply by sending an email describing the incident and attaching evidence such as a photo or a receipt of the purchased product or service. Officials of the DNCRP can also be contacted directly over the phone to seek help about how to register a complaint. People can also watch the video footages of the public hearings and awareness raising workshops and read about the resolved complaints on DNCRP's Facebook page. "We regularly conduct raids in kitchen markets and shopping malls to monitor the quality and price of the products and quality of customer service. We also organise awareness raising campaigns there to sensitise both consumers and vendors about the law and consumer rights," adds Laskar.

Loopholes in the Law

While the decision to enact a law to protect consumer rights and DNCRP's initiatives to popularise the law are, no doubt, laudable, experts have expressed their concerns about significant weaknesses in the Consumer Rights Protection Act (CRPA) 2009.

In fact, arguing that the law curbs the rights of the consumers to seek justice, consumer rights activists and lawyers demanded that the government amend this law as soon as it was enacted.

For instance, Section 60 of the Act states that "No complaint will be accepted if the complaint is not made within 30 days of arising the cause of action of any anti-consumer rights practice."

However, as Ghulam Rahman, President of Consumers Association of Bangladesh (CAB), points out, Bangladeshi consumers have limited, if any, knowledge of the law and the procedure of filing a complaint. "It is very likely that they might need some time to know about the law and figure out how to file a complaint. Such restrictive clauses can discourage people to seek justice when their rights are violated," he argues.

Another restrictive provision of this law is Section 71(1) which states that a consumer cannot file a case directly before the court of the magistrate under this law. All cases under this law have to be filed to the "Director General or any officer empowered by him or a District Magistrate or any Executive Magistrate empowered by the District Magistrate." If these authorised officials feel the necessity to file a certain case to the court of the judicial magistrate, then they will file it on behalf of the complainant. However, if they do not file that case before the court of the judicial magistrate within 90 days of the complaint being made, then the magistrate "will not take cognizance of any offence" (Section 61, CRPA).

Eminent jurist Dr Shahdeen Malik argues that the most significant drawback of this law is that if a complainant does not get justice under this act, s/he has no recourse at all. "If s/he files any case before the court of the magistrate after being rejected by the DNCRP, chances are high that s/he will not be able to convince the court as it has already been solved by the DNCRP. So, this law has actually curbed the rights of the consumers while empowering the bureaucrats," he says.

However, Shafiqul Islam Laskar, the Director General of DNCRP, states that the organisation has already taken various steps so that people can easily file a complaint as soon as they encounter the defect of the purchased product or service. "Till now we have solved all the complaints filed by the consumers. However, if we feel that a particular case should be forwarded to the court of the judicial magistrate, we shall do that on priority basis," says Laskar.

What can we do?* About any anti-consumer rights practice you can file a complaint at: |

What the Act Exempts

Another major criticism of the law is that it does not permit the DNCRP to file a case against adulterated or fake medicine, although it has the power and responsibility to investigate adulteration or faking of medicines (Section 72, Special Provision on Medicine, CRPA). Likewise, under this law, DNCRP can inspect and detect defects in private health care service but cannot take any remedial measures against them. They can only inform the matter to the Secretary, Ministry of Health and Director General, Department of Health (Section 73, CRPA). The Act also exempts sellers or owners of shops who sell adulterated or defective products, if the products are manufactured in a licensed factory and if they have no involvement in the manufacturing process.

"These provisions of the Act have actually provided indemnity to the vendors," argues Dr Malik. "In many cases, medicines get damaged as they are not stored in the required temperature by the sellers. If a person becomes sick by taking these medicines, the seller cannot be held responsible as he is not involved in the manufacturing process."

In this regard, officials of DNCRP argue that the organisation does not have that technical capacity to take decisions about the quality of medicines or health care services. "We can take immediate steps against the seller or manufacturer of a service or product as long as we can measure its condition by observing its physical appearance, for example by seeing its date of expiry or even its damaged condition resulting from faulty storage facility. However, if further investigation is needed, we have to seek help from other relevant organisations like Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution or Department of Health," explains Laskar.

Following harsh criticism from consumer rights activists, the then commerce minister promised to amend the Consumer Rights Protection Act in 2011, but since then, no steps have been taken. DNCRP, on the other hand, believes that if people can be made aware of this law and consumer rights, consumer protection can be ensured through this legal framework.

Consumers' Woes

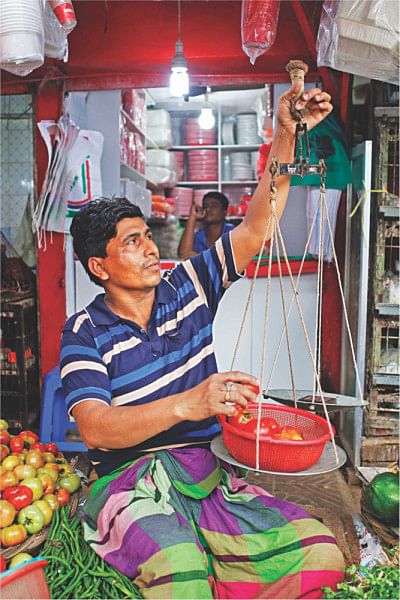

It is evident that Abdullah's experience describes little about the vulnerable state of consumer rights protection in Bangladesh. Inadequate market surveillance, monopolisation, ambiguous legal framework and people's low awareness of the law and their rights are some of the significant reasons behind the growing plight of Bangladeshi consumers. Price hikes, food adulteration, toxic chemicals and preservatives in food and cosmetics and use of false balances are widespread in Bangladeshi markets which have been violating the rights of consumers extensively.

As per CAB, Bangladesh's legal framework does not permit consumers to play any role in deciding the price of the commodities whereas price hikes of essential commodities affect the consumers most. "Every Ramadan, because of the syndicate of importers and vendors prices of essential commodities like edible oil, rice, lentils, gram flour, vegetables increase manifold but we, the consumers, can do nothing about it," says Ghulam Rahman, President of CAB.

"Rights of the consumers, in this regard, are so utterly violated that consumers have been conditioned with the long, sustained culture of the violation of their rights," he adds. He also argues that it is extremely tough for the government to supervise the huge market of Bangladesh which is infested with anti-consumer rights practices.

Protecting 16 Crore Consumers

In Bangladesh, the mammoth task of sensitising 16 crore people about consumer rights is shared by only two organisations: CAB and DNCRP. In India, there are more than 200 organisations which work to protect consumer rights. In Indonesia, there are 130 non-government consumer rights organisations and they receive regular incentives from the government. On the other hand, CAB is the only noticeable non-government organisation in Bangladesh working on this important issue. With only four employees and no government incentives, the organisation can hardly make any lasting impact. And, DNCRP, the government body to ensure consumer protection, is also over-burdened with scarce manpower and the huge responsibility of overseeing consumer rights protection all over the country.

Although the government is trying to move forward to ensure consumer protection, with such significant loopholes in the legal framework, it would be impossible for the government to ensure consumer rights protection in the long run. Amendment of the law is necessary and consumers should be empowered to play a role in deciding the price of essential commodities. In this regard, more NGOs should be encouraged to work on consumer rights issues.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments