Communalising culture

In school, we were made to memorise definitions of culture and civilisation, marking a relationship between the two. The definition of culture went somewhat along the lines of “the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, defined by everything from language, religion, cuisine, social habits, music and arts.” Cultural identity was meant to encompass our common, ever-changing heritage. Looking back, the definition seems somewhat childish: the history of the sub-continent is definitely not one of a fixed shared identity. It has always been in flux, morphing according to the relationships between castes, religions, and nationalities. But this definition of culture has one important insight: pointing towards the multiplicity of factors that constitute a cultural identity, it hints at an amorphous nature, not a monolith.

It seems, many of us have failed to grasp this from our studies. The question of identities is a deeply political one, and in Bengal, it has led to riots and communal violence. We have always seemed to be suspicious of our plural identities: socio-economic reasons have created binaries, where you can be either one or the other. Why else, even today, are we constantly in fear of what label our thoughts and acts might earn us? Why the question of are we Muslim or Bangali the first one we ask? Is it not possible for us to be both?

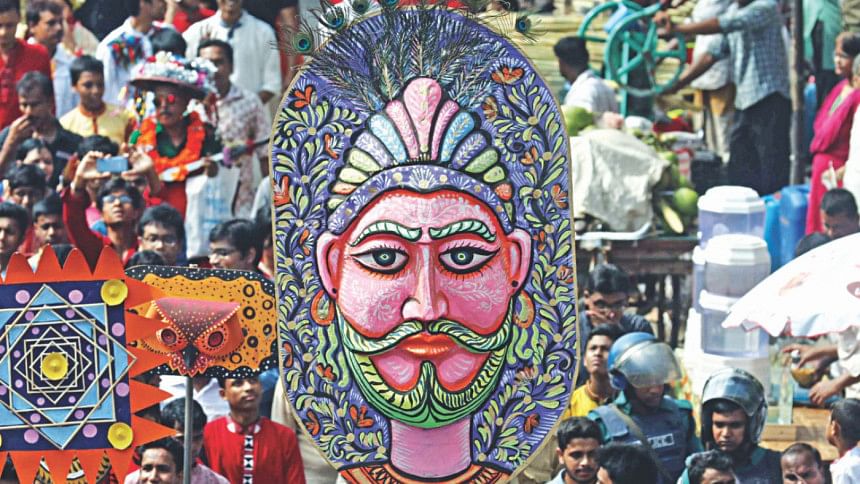

Every year, around this time (more so recently), a section of the population seems to be unsure about celebrating Pahela Baishakh. Now, Pahela Baishakh is a tradition that spans across centuries in Bengal. The celebration of the New Year through the Mongol Shobhajatra, though fairly recent, has already earned its place among UNESCO's list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Yet, this year too, some factions have protested that the Shobhajatra – which literally means the procession heralding welfare – cannot be part of our national heritage: it is too Hinduani (smacking of Hindu-ism) for them. Fundamentalists, who cannot see a man's identity beyond that of their religion, argue that in a country where the state religion is Islam, the Shobhajatra, with its colourful parade of folk art, masks and floats, is anti-Islamic. Some prudent moderates, not wishing to seem irreligious, venture a less headstrong argument: the Shobhajatra is only a few decades old. How can something this relatively new be part of our Bengali culture?

This is nothing short of communalisation of culture. It seeks to define an identity, which the majority of the nation must conform to, while making “others” of the minorities. It seeks to take something as colourful and secular as a procession of floats decked out in folk arts and give it a religious identity. The history of the Shobhajatra is an interesting story, and one which, I would hope, for the moderates would dispel these silly notions.

An article on Scroll.in published this January, reads: “In 1985, an art school called Charupeeth in Jessore town in Bangladesh, in a bid to showcase the culture of Bengal, organised a procession marking the struggle for the Bangla language, which is observed as Martyrs' Day on February 21. Its success prompted the organisers to bring out a surprise procession on the first day of the Bengali New Year. Around 300 participants, including school children, wore colourful masks and dressed up as traditional Bengali kings, queens and fairies, and as flowers, birds and butterflies. They took care to avoid any overt religious symbolism as they wanted it to be a celebration of the common cultural bonds of the Bengali homeland that cut across religions.” In the political mayhem that was the 1980s, which also saw the resurfacing of defining our national identity in terms of religion, a group from the then Charukola Institute, including sculptor Mahabub Jamal Shamim, print artist Moklesur Rahman and painter Heronmay Chanda, took out the first of the processions along the lines of the school in Jessore, emphasising our Bengaliness. It was a sharp distinction to General Ershad's use of religion in politics. It sought to rise above the Islamisation of the country's politics and identity through a celebration of our national identity.

Of course, the reasons that a communal interpretation of something that is secular, has managed to gain footing has a historical basis. But, looking at this religious divide in terms of the British classification of the subcontinent into Hindu and Muslim is misleading. Research by the likes of Richard Eaton and Romila Thapar has dispelled these notions of purely divided societies, and has shown how the two beliefs have found ways to accept each other. It did not always succeed, and to deny the existence of one community oppressing the other would be wrong. It would be equally wrong to use the socio-economic realities of colonial India to justify the blatantly communal identities that some groups are today trying to leverage.

But, these subtleties are lost on many. It is prudent to understand how socio-economically discriminated masses are mobilised in the name of a certain ideology. It, however, does not explain the deep communal biases that permeate our educated middle-class. As I write this, I read a report about how a writ petition has been filed in our courts to remove a statue of lady justice from the High Court premises. That does not shock me; what does, is that on social media, I see people questioning if the Greek deity of justice has a place in our culture; or why the statue is clad in a saree, a non-Greek attire. That we are having this debate is symptomatic of wounds left untreated. Instead, we have further deepened it. While the secular elite has brandished words of wisdom unheard, the fundamentalists had been allowed to sow their seeds deep. It is unwise in this country now to question how it can have a state religion and be secular at the same time. Stories and essays written by non-Muslims seem to disappear from our textbooks, apparently with no one knowing how.

What has resulted is the politicisation of an event which brings people together in a colourful festival. The prevailing culture allows the questioning of this in communal terms, and has made a spontaneous celebration, one of apprehension. Now the Shobhajatra is supposed to be heavily guarded by the police. Yet the deep communalism which we have left unchecked and allowed to fester for years creeps in insidiously. We forget, and sometimes it is unwise to remember, that our identity is not a rock and our culture not a fossil. We have our communal baggage as we have our secular glories. The tales of Bonbibi in the Sundarbans for one speak of a syncretic community, as does the celebration of Baishakh through the Shobhajatra. It celebrates the common fold themes that we have as our heritage.

The debate one should have about the celebrations of Baishakh is if its scope can be broadened to include strands from all communities, not just Bangali. If it is time we stop prioritising our Bangali nationality to look for a more plural identity. Instead, the narrative of whether the Shobhajatra is Hindu or Muslim, with its eyes turned towards a distant glorious past, seems to forget how cultures are shaped, yearning to return to a truly Muslim identity. We forget that one can be as much a Muslim in Bangladesh, in its local culture, as in America. Every time we give leeway to the debate, make a compromise, we further fuel the hatred that pretends to be religious. Let us see Pahela Baishakh for what it is, a shared bond that transcends our religious identity in a subcontinent with a bitter communal past.

The writer is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments