Realities on the ground

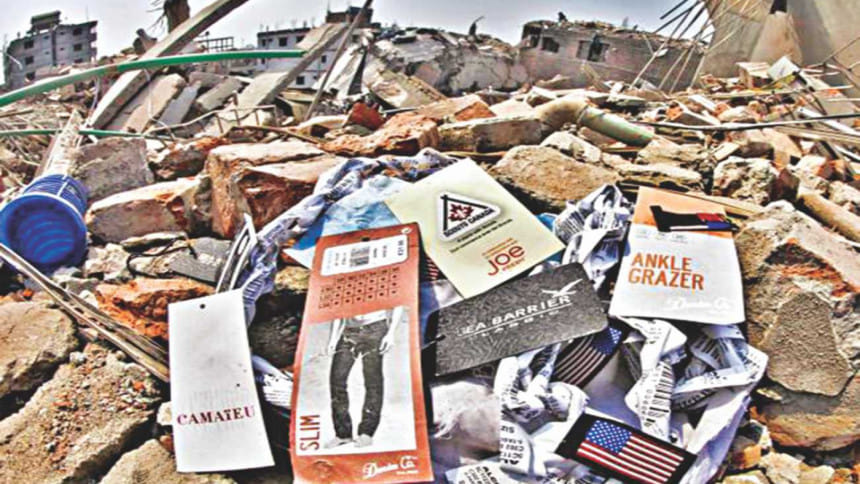

The Rana Plaza collapse that killed around 1,100 people put western retailers at the brink of pulling out their business from Bangladesh. Stronger measures for structural workplace safety were put into place and implanted through the Accord and Alliance and ties with multiple non-compliant factories were severed.

Nevertheless, we hear often through state representatives that European and American customers are very concerned about what working conditions their clothes are made in. If that concern is valid, how much of a financial hit did the brands take, especially the ones who were involved in Rana Plaza?

Rationally speaking, there should have been a drop in sales or share prices, right? Wrong. In an article in The Guardian in 2013 it was stated that Primark, one of the brands involved in the industrial disaster, saw 20 percent rise in sales and that "good weather outweighed the negative publicity".

The catastrophe left behind by Rana Plaza is not the first case where dire working conditions of large clothing retailers were exposed. There are cases of factory collapse or underage workers in competitor countries like India and Cambodia. This ideally should have made the "concerned" customers of Europe and America more reluctant to buy clothes from big brands in business with those factories. Yet owners of fast fashion companies like Zara or H&M are some of the richest individuals on earth. This was possible because these companies have succeeded in selling cheap clothes in bulk.

Even though in the context of Bangladesh we see a lot of pressure on safety and social compliance, our manufacturers often express concerns that they lose orders as the cost of business has become higher due to those measures. That makes perfect capitalistic sense because our buyers don't come here to boost our economic growth but rather to source clothes at a competitive price and profit from cheap labour and working conditions. If and when cheaper alternatives arise somewhere else they will move their businesses there. Like any other business they just want to maximise profit.

This raises the question about whether the issues of social compliance and sustainability at the core remain a one-sided effort systematically. The upcoming review of the EU Sustainability Compact is on May 18. If the review sees no significant development in regards to workers' rights, the EU might consider revoking the preferential trade facility, Everything but Arms (EBA), for Bangladesh. Undoubtedly, Bangladesh and its RMG industry have benefitted a lot from this duty-free/quota-free access to the EU. However, concerns about the lack of regard for workers' rights, namely freedom of association, resulted in Bangladesh getting a special paragraph mention in the 2016 International Labor Conference.

Now, let's think for a moment what would happen if Bangladesh actually lost the EBA preference. The cost of doing business would be higher and buyers would move to cheaper destinations. It doesn't necessarily mean that our competitors are better than us in terms of compliance and safety measures. In the end, the single deciding factor is price. In the aforementioned scenario, our competitors would enjoy an increase in business. However, the challenges that are relevant for us most likely will be relevant for them too one day.

All these dynamics are reminiscent of another industry that has historically struggled to get fair prices—the oil industry and OPEC. In the 1960s there was a globalised oil market when the demand for oil was increasing. However, the oil-producing countries were not the ones benefitting as global production and prices were controlled by five western companies, including Shell and BP.

The OPEC then came in to give power back to the oil-producing countries by regulating supply and manipulating prices, thus becoming a cartel. An example of their action is the oil embargo of 1973-74 against the US and other industrial countries which supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War, causing significant rise in oil prices. The context, dynamic and nature of the oil and apparel industries are different but there are definitely things to learn from history about industries that have faced similar challenges as us when it comes to fair prices.

Although the issue of fair price is important to achieve sustainability, it doesn't however exonerate the local stakeholders from their obligations. Labour representatives and their advocacy partners have rightfully pointed out that employers are yet to show proactive efforts and truly value labour as their business primarily depends on competitive prices. Much of the progress in workers' rights, safety and wellbeing has been achieved through international pressure rather than reforms on our own. Yet, this is nothing new. Historically, labour has always been exploited: slaves of ancient Egypt and America, coal miners working in unsafe conditions during the Industrial Revolution, domestic household workers in our country who have no institutional rights or liberty, etc.

But we have always made progress in terms of improving our conditions through other means. RMG factory workers are constituents of a republic with voting rights. Thus there is a strong incentive for governments to design and firmly implement legislation that caters to their needs. It is important that workers are able to form associations and have a dialogue with their employers and make their voices heard through proper representation. There is a need to work on the growing mistrust between the two parties.

At present, only four percent of workers are represented through unions and most applications for union registrations face considerable bureaucratic challenges and arbitrary rejection. The nature and the quality of social dialogues will evolve and improve over time but we must act now to make meaningful progress. It also makes economic sense as an environment conducive to such progress will prevent catastrophes such as Rana Plaza and unrests like the protest in Ashulia. It will allow the smooth operation of businesses and overall expansion of the RMG sector that still accounts for around 80 percent of our export revenue.

The writer is a development practitioner.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments