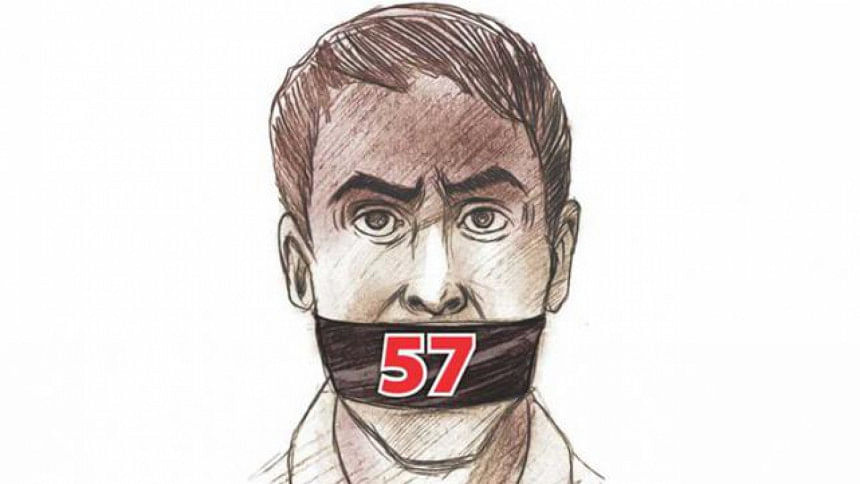

Opinion: Who will save free speech from police?

Law Minister Anisul Huq's assurance of deletion of the ICT Act's section 57, a draconian provision which threatens free speech, did not offer much comfort to media people along with free thinkers.

It is because the same draconian provision has been included in the proposed Digital Security Act which was approved by the cabinet last August.

READ MORE: Section 57 to be dropped from ICT Act

According to section 57, if any person deliberately publishes any material in electronic form that causes to deteriorate law and order, prejudice the image of the State or person or causes to hurt religious belief the offender will be punished for maximum 14 years.

Legal experts have unequivocally been saying that the section 57 goes against people's right to freedom of expression and free speech. The section contains vague wordings, allowing its misuse against newsmen and social media users.

Today, talking to reporters, the law minister himself acknowledged that the section 57 of ICT Act is a hurdle to the freedom of expression.

READ MORE: Section 57 goes against freedom of expression; vagueness creates scopes for misuse

He also assured that the section 57 will be removed from the ICT Act. He said the confusion and ambiguity of the provision introduced by section 57 will be removed in the new Digital Security Act.

But the reality gives a different picture.

The controversial section 57 got embedded into the proposed digital security law.

The proposed digital security law seems to have offered police much more powers to make arrest.

The ICT Act empowers police to make arrest without a warrant after a case is filed against someone in connection of allegedly committing offences using electronic devices.

Alongside social media users, a number of journalists have been arrested by police under the ICT Act.

But police can arrest any person on suspicion that he has committed offences under the proposed digital security law. Police had used such authority in exercise of draconian section 54 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to arrest anybody on mere suspicion. A few months ago, the Supreme Court has in a verdict outlined some guidelines to stop arbitrary use of the blanket power of police.

It is significant to note that the government in 2011 limited the court's powers to directly issue arrest warrant against journalists, writers and others for writing or saying anything defamatory. An amendment to the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) introduced a provision for issuing summons against them.

In 2013, in an amendment to the ICT Act, the government further curtailed the courts' powers. Earlier under the ICT Act of 2006 police had to seek permission from the courts to make any arrest.

But the amendment repealed the provision for taking permission from the courts to make any arrest without arrest warrant issued by the courts.

Indian Supreme Court in March 2015 declared unconstitutional the same provision in Indian ICT law which had provided the law enforcers with arbitrary and discretionary powers to make arrests.

Bangladesh government, however, opts for retaining the draconian legal provision. Section 57 may be removed from the ICT Act. But the same legal provision will remain in the proposed digital security law allowing police to use discretionary powers to make arrests.

The British rulers were against freedom of press and free speech. During the colonial rule, the provision of CrPC was made empowering courts for issuing direct arrest warrant against anybody including journalists, writers and publishers of any books or newspapers if they wrote or said anything defamatory.

But, now not the courts, the police forces are empowered to make any arrest after filing of a case under the ICT Act on charge of defamation.

Police will have more arbitrary and discretionary powers in the proposed digital security law as they can make arrest on suspicion too.

The punitive measures introduce by our government are also harsher than the ones made by the colonial rulers.

Under the Penal Code of 1860, one may be punished with simple imprisonment for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both for defaming other.

But one may be punished up to 14 years to imprisonment for defaming other under ICT Act. In the proposed digital security law one may face maximum seven years of imprisonment for defaming other.

Which one is more repressive law: the one made by the colonial ruler or our government?

Are we moving forward or backward?

The other crucial question is: who will save free speech from the police as the government keeps giving the law enforcement agencies more discretionary powers.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments