Fighting the financial hemorrhage

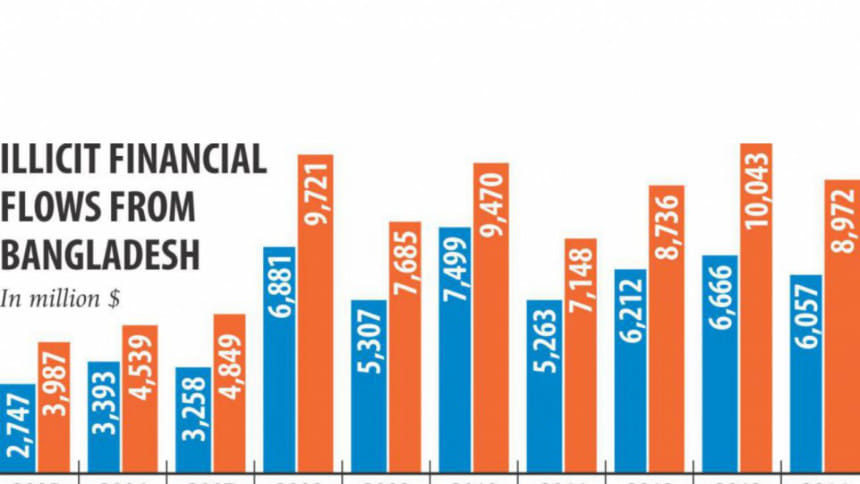

We live in a notoriously polluted city of the world, and still we choose to live here because we have a dream. We live in a system where justice is badly delayed for generations, and still we choose to live with the hope of having a prosperous Bangladesh one day. How will that dream come true when a big segment of the affluent turns viciously ungrateful to their motherland that provides high returns to businesses and collects the lowest tax in exchange? The Global Financial Integrity Report revealed that Bangladesh lost almost USD 75 billion over a decade (2005-2014) and USD 6-9 billion in 2014 alone. This is a growing cancer for the economy of a country whose journey towards becoming a developed nation will definitely be delayed if the hemorrhage continues. Devising preventive measures is a national emergency.

The spike in illicit outflow first happened in 2008, rising from USD 4 billion to 8 billion. We understood the reason; it originated mainly from the military-backed caretaker government and the ensuing uncertainty that clouded the investment sky. It was slightly low in 2009, in the wake of the newly elected regime, and we thought illicit outflows will decrease. But that did not happen, belying the myth that political stability is an antidote to money laundering. From 2009 to 2014, we experienced a hemorrhage from USD 5 to as high as USD 10 billion every year, without any sign of abating. Of course, the country lived through political agitation, particularly during late-2013 and early 2014, and again in the first three months of 2015. But the pattern of money trafficking maintains its course stubbornly, suggesting an in-depth research into the matter.

Even a continuing trend in the subsequent years will not surprise us, because we are convinced that the reason lies somewhere else. A systemic vulnerability prevails. If the system is leaky in itself, investigation is weak, financial intelligence is weaker, and the culture of punishing the criminals is the weakest, illicit outflows will enjoy their spring every year. The typical apparatus for the surveillance of money laundering is ineffective. Despite having macro stability and commendable economic growth, we notice two things happening together: a burgeoning default culture and money laundering. Are they interlinked? Highly possible. A rigorous inquiry is needed.

Whenever an inquiry committee is created, we know for sure it will be headed by government officials, and eventually the report will not see the light of day based on various 'public interest' excuses. Let us break the format. The best way to deal with money laundering is to form at least three totally separate, independent investigative bodies: one from the government, one private, and the rest from international experts. Not only will they investigate the loopholes, but suggest feasible solutions to prevent the fund-drain. We are sure that three bodies, if they really can work independently, will come up with multiple findings to stem the resource flight. Spending on quality intelligence and research is the last thing our governments want to do. Money laundering will never be stopped without changing this mindset.

How much money do we need to spend on a multi-body investigation? Eight million dollars, which is equivalent to Tk 64 crore, is enough to run such studies engaging authorities and researchers of different spectrums. The proposed study cost is less than 0.1 percent of the money we lost in 2014 – the money we are likely to lose every year since. Herein lies the cost-benefit analysis of research. We hope we will be lucky enough to see the timely release of the inquiry reports.

Money is siphoned off mainly through misinvoicing. Say, an importer buys a good worth USD 60 from the US. He will request the US counterpart to make an invoice for USD 100 – an act of overinvoicing. Here, the importer will arrange to send USD 100 to the US party who will keep USD 60 for his own product and park the surplus USD 40 in a designated account favouring the Bangladeshi importer. In contrast, a Bangladeshi exporter will resort to underinvoicing for capital outflow. Say, he has shipped a container worth USD 110 to the US but sent an invoice of USD 80. The US party will send USD 80 to Bangladesh, and keep the other USD 30 in an account as advised by the Bangladeshi exporter. Thus, a total of USD 70 becomes the amount of money laundered from this country. Remittances when operated under hundis give another conduit for illicit financial outflows. A high amount under the heading of 'errors and omissions' in the balance of payment seems to also have indulged illicit money flows.

Let us not undermine the gravity of Bangladesh's capital loss by defining it as a common phenomenon for developing countries. This is true, but the magnitude matters emphatically. India's economy is more than ten times larger than ours, but India's fund outflow is only three times larger than Bangladesh's. We feel embarassed when Pakistan's example stands out. Their economy is bigger than ours, but their laundered money in 2014 was less than one percent of Bangladesh's. Is it not a shame when Pakistani money launderers prove to be more patriotic than their counterparts in Bangladesh?

The amount we lost in 2014 alone can build two Padma Bridges. The amount we lost only in 2015 is good enough to build a basic Patalrail for Dhaka. But the issue is, if we could have somehow prevented that money from flowing out, could more mega bridges or a Patalrail be built? Probably not. We already have USD 35 billion in the aid pipeline, and a government machinery cannot solely use the money.

That is another reason why money laundering continues. Public investments behind infrastructure, energy, and institutions must be accelerated to revert the premature fatigue of growth trend. An attractive market economy will discourage money laundering. An investment blitz definitely needs decentralisation and competitive outsourcing of construction works. Then the same money launderers might turn into 'patriotic' domestic investors overnight. A series of brainstorming sessions after the budget should kick off to rip up the wings of illicit financial flows and to make a vibrant Bangladesh.

The writer is visiting fellow at Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) and guest faculty at the Institute of Business Administration (IBA), Dhaka University.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments