Remembering Syed Abdullah Khalid

Year 1979.

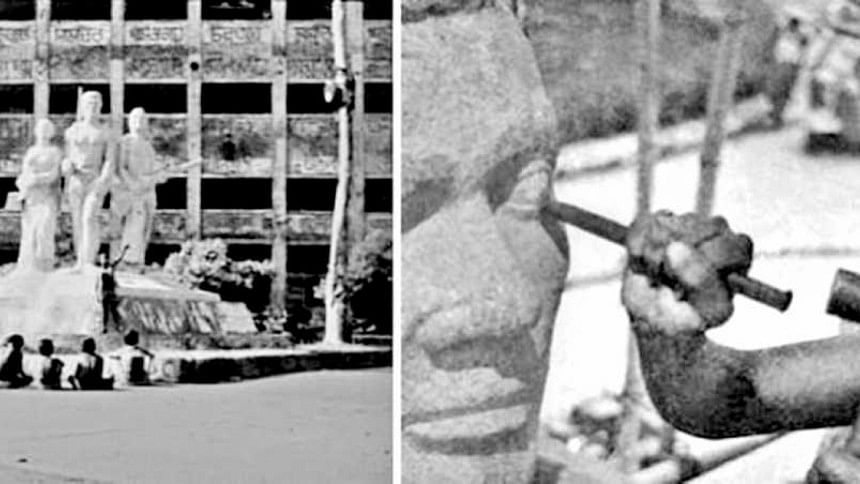

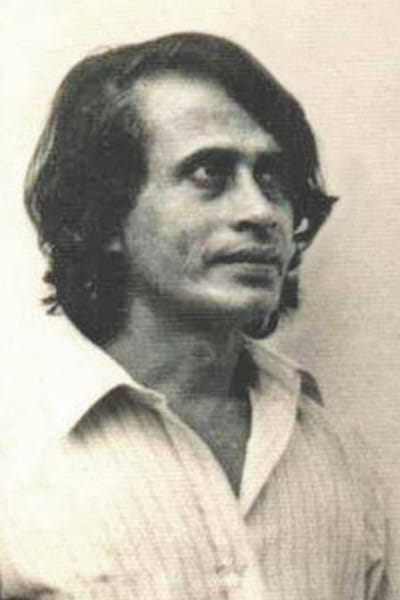

A long haired young sculptor was regularly seen near the arts faculty of Dhaka University, with a hammer and chisel in his hands, working day and night on a life-size structure. Even as curious pedestrians, rickshaw pullers, and university students gazed up to see what he was doing, the sculptor religiously worked on his sculpture, to finish what he started. Finally in the month of December, the structure was complete- three freedom fighters representing the liberation war of Bangladesh.

On December 16 of the same year, Aparajeyo Bangla (Invincible Bengal) is inaugurated by wounded freedom fighters whose faces shone with pride and honour.

Khalid shares that this sculpture was a work of labour and perseverance. During the war of 1971, he had the chance to work closely with freedom fighters, however, he himself did not participate in the war directly. “I always had an indomitable desire to fight in the liberation war holding guns in my hands, but I could not do so,” says Khalid with great remorse. “Since then I wanted to create an art work which would symbolise the struggle of independence, the blood, toil and tears sacrificed by our valiant soldiers in our war of independence,” he adds. In 1973, when he was working as a young faculty member at the department of Fine Arts in Chittagong University, the Dhaka University Central Students' Union committee commissioned him to build a monument that would depict the glory of the Liberation War. “I started looking for people who would model for my miniature scale structure. In my layout, I planned for three figures where the centre one would be a farmer with a rifle on his shoulder and grenade in his hand. On the left side there would be a lady with a first aid box in her hand and on the right side there would be a student who would represent the young student body who took part in the war,” he says.

The job of posing as live models was not a simple feat. Hasina Ahmed, Syed Hamid Moksood and Badrul Alam Benu, who were all close friends of Khalid's, agreed to be a part of this noble project. “I used to work 12-14 hours on average everyday to create my three-foot miniature scale model. My models would dedicate three hours for this project everyday for three months,” he recalls.

As he finished working on the miniature model, Khalid started working on the actual structure with a meagre budget. “As the budget was very low, I had to use a material which would be cost-effective,” he says. He went to Engineer S M Shahidullah in order to build the basic structure. “When I consulted him, he advised me to use the cheapest material, reconstructed concrete. If we would use materials like bronze or marble we wouldn't have been able to complete the project within our budget. His firm Shahidullah Associates built the inner structure using rods at no cost,” the sculptor recalls gratefully. During 1974, he started work on site. However, on August 15, 1975, the work abruptly came to a halt because of the shocking murder of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and most of his family members. The work could not continue because of the political instability and the arrest of the then Vice Chancellor of Dhaka University, Abdul Matin Chowdhury.

“I had to face constant obstacles posed by the religious anarchists. The continuous pessimistic reaction from the bigots slowed down the process. Some fanatics tried to demolish the sculpture in 1977. However, the courageous student body of Dhaka University protected the structure actively. After a long interruption, the work began once more in the beginning of 1979 and continued throughout the year,” says the sculptor.

After a brief meeting with the Vice Chancellor of Dhaka University, Khaled restarted his work on carving the figures but his job seemed to have become more difficult than before. While working, his hands became swollen with bruises and cuts. “Shahidullah built the mould over the structure with stone and cement in a ratio of 2:1. Four years of interval made that surface stronger and more concentrated. Whenever the hammer struck the structure it would spark with fire,” he reminiscences.Interestingly, when Khalid would hammer away on his sculpture, another young man would wander around the site with his newly bought camera. He was the broadcast journalist Mishuk Munier. In a documentary called “Aparajeyo Bangla (2011)” by Saiful Wadud Helal, Munier explained his experience of taking photos of the sculpture as an interesting process of learning. As Khalid worked tirelessly, Munier would experiment with light and exposure with his camera through photographing different moments. Soon they developed a friendship. As Munier says in the documentary, sometimes Khalid would totally ignore the fact that he and his work was being photographed, and that's what enabled Munier to capture beautiful candid moments on his camera.

Even though Khalid is mostly recognised for this remarkable creation, he has created some of the most exquisite large-sized realistic sculptures the country has ever had. Throughout his artistic journey Khalid has created sculptures of different shapes and sizes, using different kinds of material like cement, stone, fiber glass, ceramic and clay and a variety of processes and techniques. Many of them depict our glorious history of the language movement and the Liberation War. Besides these, this multitalented artist's unique murals in pottery, metals or mosaic can be seen on the walls of many residences and office buildings of the country.

Some of his works include a Shaheed Minar called 'Ankur (The Bud)' at the factory premise of Squibb Pharmaceuticals, a mural called 'Abahaman Bangla' inside the premises of the Bangladesh Television Center in Rampura, a monument for martyrs called 'Angikar' in Chandpur, the Shahid Minar of Chittagong University and a terracotta relief mural called 'Toiling Masses' in the conference room of the Daily Ittefaq.

Since its establishment, Aparajeyo Bangla has been more than a concrete-built sculpture standing at the centre of Dhaka University. It has been serving as a platform which has cultivated and nurtured several student leaders. Be it a short and blood-stained political revolution or a slow and peaceful pedagogy waging between students-educators, Aparajeyo Bangla has always worked as the forum where our next generation of innovative leaders have gathered. The three figures symbolising the spirit of youth have actually managed to drive various generations of youngsters to revolt against atrocities. Just like its name, Aparajeyo Bangla has over the years come to represent the independent psyche of the freedom loving Bangladeshi people. It truly tells the story of a country that was invincible back when it was fighting for its freedom against occupying forces, and now when its people are once again fighting intolerance, violence and instability.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments