Cathartic and self-destructive

"Revolutions begin fighting tyranny and end fighting themselves."

Carlos Fuentes quoting Louis Antoine Saint-Just, the French revolutionary guillotined in the combat between the factions once united against the monarch

The Underdogs by Mariano Azuela, the first of the novelists of the Mexican Revolution, is a modern epic set at the height of legendary general Pancho Villa's fame and ends two years later, when Villa is suffering heavy blows in the fight between the two factions of revolutionaries—the Conventionists led by Villa and Emiliano Zapata and the Constitutionalists led by Venustiano Carranaza and Álvaro Obregón. However, as suggested by the title, the setting of the novel is not the battlefields of these famed leaders. It follows Demetrio Macías, the peasant-warrior, and his band of 20-odd rebels, from humble beginnings to periods of intense battles and much glory, and ultimately back to Macías's original point of departure—the darkness of the Mexican Sierra.

The original Spanish title, Los de abajo, literally translates to “those from below”. Demetrio and his men are without a doubt from below, in an economic and social sense. Under the 30-year rule of dictator Porfirio Díaz (1876-1910), Mexico had experienced limited economic development. While industrialisation through the investment of foreign capital and modernisation of the transportation system provided some of the necessary constituents of a modern capitalist system, the rural lands and agricultural workers who formed the majority of Mexico's labourers, or peons, remained firmly under the control of the semi-feudal hacienda system. By questioning the registered titles of ejidos, land farmed communally, Díaz made more land available for the landed gentry. By 1910, over 90 percent of the villages in the central part of the country had lost their lands, while some 30 percent, the majority of the landless rural population, remained immobilised and chained by the debt to the hacienda. The protagonist and his men are thus subjects from the lower rural classes who had been excluded from the benefits of Díaz's modernisations, the very classes who rose up in the revolution.

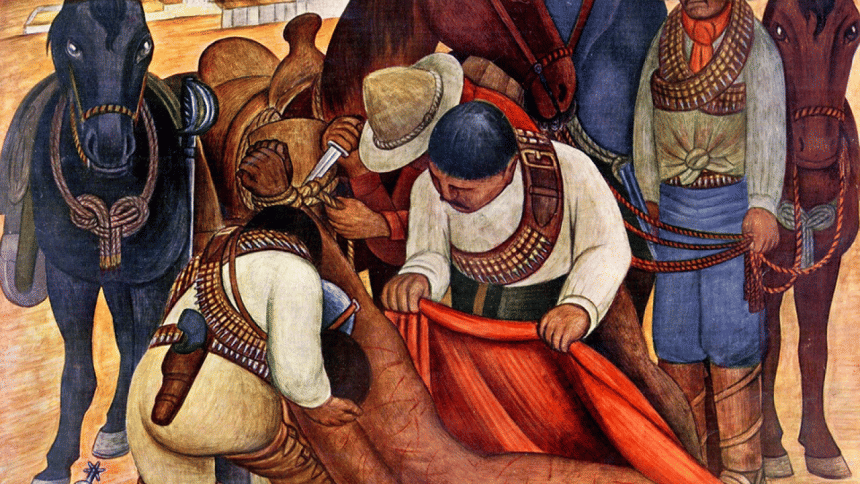

However, as with any frank treatment of war, lines blur in The Underdogs. Ex-federal soldiers join the revolutionaries, and the heroes become the plunderers and the rapists they once fought, as the mantle of power shifts. As the rebels overpower the federales, a newfound freedom is found, one that is completely unbridled and lawless. Thus, in the words of the translator Sergio Waisman, the novel is “replete with ambiguities”. Fuentes also asks in the foreword: “Is the novel revolutionary—in the way it underscores the poverty and ignorance of Mexico's peasants and lower classes, and the injustices separating their condition from that of the few land-owning elite? Or is it counter-revolutionary, in the ways it reveals the barbarism and banditry of those who fought on both sides of the revolution, thus suggesting that the objectives of the revolutionaries were personal in nature, as opposed to ideological?"

While the readers may come to their own conclusions, it is unimportant to resolve these ambiguities. There is nuance to the havoc. The vandalism and expropriation of property and possessions by the revolutionaries is an unavoidable evil, if not a necessary one. It is cathartic—a destruction of the symbols of the ruling and land-owning class, a liberation from the past power structures.

However, as in the example of the devaluation of a stolen typewriter, from ten pesos to a quarter, and its eventual destruction, these acts paradoxically reflect a lack of appreciation and understanding for the new instruments of power. As Beatrice Berler outlines in her paper, The Mexican Revolution as Reflected in the Novel, under Díaz's regime, schools in the small communities and villages were closed. Knowing that an educated populace is not easily subjugated, he allowed them only in the larger cities for the exclusive use of the wealthy class. Thus, the rebels had been self-destructive and short-sighted, their actions ultimately not useful towards the very re-organisation of the economy that they had been fighting for.

Thus, The Underdogs neither focuses heavily on the premise of the revolution nor does it attempt to justify its byproducts. In this way, it is a thoroughly critical account of the underdog, the little guy who does not understand the big picture. Indeed, it is only the self-serving intellectual Luis Cervantes, a physician and self-disparaging stand-in for Azuela himself, who survives the war and thrives in the end.

Ending on an ellipsis, Mariano Azuela points out that even if the battle is over, the revolution is far from it. In the words of Saint-Just, it is only “when a people, having become free, establish wise laws, [that] their revolution is complete.”

Comments